Interview with Art & Language. A Conversation in the Studio About Painting: David Batchelor

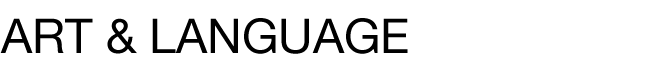

Art & Language. Hostage XIX, 1989.

David Batchelor: This series of Hostage paintings can be broken down into four more or less distinct elements - the landscape, the coloured band, the areas of compressed paint, and the glass — which, in the finished works are made to interact or interfere with one another. I would like to talk about these elements, starting with the landscape. I know the motif derives from an actual row of trees in a nearby field, but in the paintings they seem to exist more as a landscape token, a landscape-in-quotation-marks, than the result of direct observation. This is partly because the motif has been repeated so many times.

Mel Ramsden: We had always had an interest in painting something which has a certain local existence - something somehow incompetent in respect of a secular, cosmopolitan, modernism.

DB: Have you painted landscapes before?

Michael Baldwin: We painted an oak tree in trying to augment the Portraits of VI Lenin in the Style of Jackson Pollock. We've tried other local scenes, often unsuccessfully. I don’t think this has as much to do with landscape painting as with landscape as an intellectual motif. The place depicted contrasts (and of course today, fails to contrast) with the site upon which our previous activity was focused.

DB: You mean the museum, as a cosmopolitan arena?

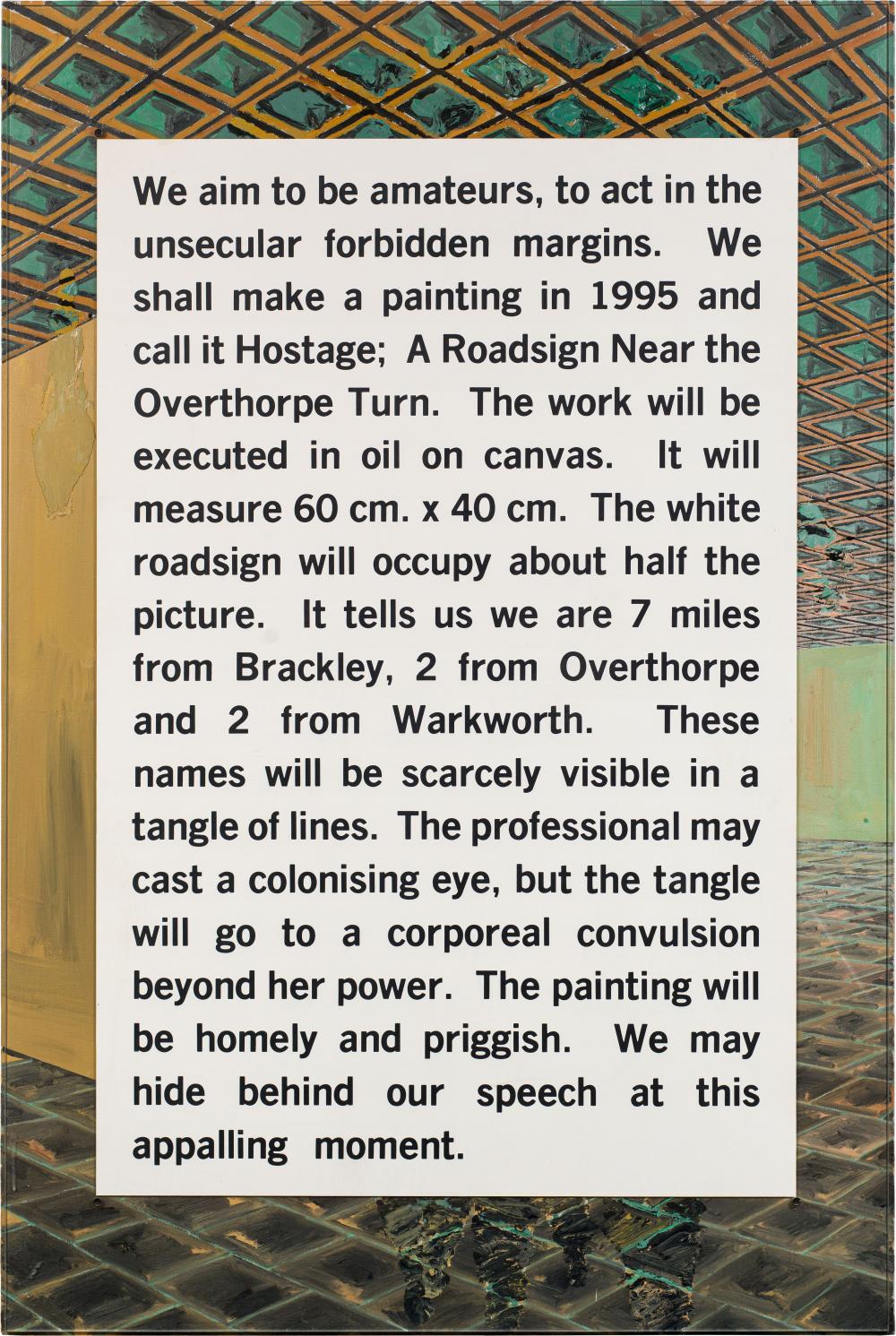

MB: Yes, as a highly tuned, culturally self-important site. With the landscape we have a relatively de-tuned, culturally un-self-important site. The landscape first occurred in an ironical conversation we had in relation to the ancestral forms of the present Hostage series. This ancestral form was a text in which we predicted paintings. These were landscapes. The text ‘predicted’ a landscape. The form of the text was culturally incommensurable in respect of what it ‘predicted’. We thought inter alia that it would be nice to be, as it were, a conceptual artist on weekdays and to do landscapes at the weekend. The text was predicting a terrible bathos for itself as a very smart item, viz a piece of concept art.

DB: I wondered whether there was any residue in these landscapes of that other series of paintings in which nature in one sense or another was invoked - the rather transitional ‘snow’ paintings?

MB: We discovered that these were radically unfinishable paintings.[1] Their ‘logical’ character was such that the point at which they were visually complete was also the point at which they were intellectually incomplete. And vice versa. We volunteered in those paintings to try to live between these irreconcilable demands — between Scylla and Charybdis. But this had very little to do with nature paintings, and very much to do with contingency, effacement and erasure. By tying this to a natural phenomenon, snow painting became a form of apparent self abnegation. We were fictively recording external contingent circumstance in which whatever we have depicted might be defaced. This in the interests of the derogation ‘something has happened to the painting’. The self abnegation is itself only apparent since the erasure was at our hands, nature a mere cipher.

DB: You have talked of the landscape as a kind of antithesis to the museum motif which predominated in your work of the previous couple of years. But it didn't seem to me that these paintings emerged simply as the negative of the museums. For example, they set up a similar kind of spatial structure to some of those paintings.

MR: Landscape has had a kind of existence in the practical activities of the studio over quite a long period. You must go back to the work started immediately after the museum paintings. We were concerned with extending these paintings to address that fatuously necessary cultural observance which is constantly to wonder ‘what's next?’ We began with the motif of the museum in the future, the ultimate non-site, as it were. At various stages this idea kept coming back to us.

MB: This was effectively always a text. A date: ‘The decade 2010-2020’. The museum as hostage to fortune.

MR: And then we tried to paint something which made us hostages to the future. If we were going to write a text which said that in 1998 we were going to paint such and such a picture, the picture had to have bathos, a kind of atrociousness which you could hardly bear to produce, a kind of disgrace.

MB: The disgrace of mere possibility expressed in words. An anecdote is instructive. Channel Four came along and asked us to be involved in a programme about framing.[2] In connection with that project we executed a very smail, naturalistic landscape. This little quasi-academic 19th-century thing was taken by the television folk, stuck in a frame and hawked around various galleries who suggested some rather ludicrous prices for it. They then took it along to the Tate Gallery, to Nick Serota. He smelled a rat. It was not the kind of thing the Tate Gallery would be buying today, he informed them. To be presented with an item like that is a curatorially appalling moment. In one of our landscape-predicting texts it was suggested that the laughter or the terror associated with realising the project entailed that we hid behind our speech; that realisation would be an appalling moment. The ‘landscape’ hides behind speech, culturally, psychologically and genetically.

DB: But it is not the point, obviously, that the Tate Gallery would react in that way faced with any landscape. Rather it has to do with the particular type of landscape. It is clearly less a question of what is represented than of how it is represented. The Tate is not at all bothered by having a number of Richard Long ‘landscapes’ dotted around the place.

MB: I don't think Richard Longs are ‘landscapes’ so much as large knick-knacks in masonry; neither are they pictures. But I take your point.

MR: And everyone knows they are more about installations and using expensive cameras really.

DB: Did you have to struggle to find an appropriate technique?

MB: It's a kind of ‘typing’ technique, effectively, in various delightful colours. I’m not even sure if it's clear that they are thoroughly exterior spaces. They were set up in such a way as to be ‘typable’ in the way the museum spaces were. They are also like the museums in that there is something like the floor, which is the field; the trees form a kind of wall: and there is an implied ceiling.

DB: Let's move across to the other side of the painting. The landscape motif is qualified in each work by the band of colour down one or both sides. Didn't these start life as a foreground wall in an early museum version of the series?

MB: This was come by more or less honestly: these trees skirt a playing field in which there is a cricket pavilion. The post supporting its veranda could actually be incorporated into the landscape. Degas uses similar foreground devices, for example.

MR: Of course you can't account for the band entirely in a naturalistic sense. It's a device, as it was for Degas. It's a bit like painting a frame, it can serve to push the remainder of the painting into something like a quotation. You can see this in Cézanne and Vermeer and Velasquez. In Degas it's almost a voyeuristic device which gives the sense of someone peeping around the corner.

MB: The band was got honestly both in the sense that it has one of its feet in observation — it is genetically connected to the landscape site, and in the sense that it is a fairly ordinary device and not only in modern painting. It's a naturalistic device which can then be tuned in various ways, in the case of Cézanne to create a kind of ambiguity, in the case of Velasquez or Degas to create a kind of psychological atmospherics — how you place yourself in relation to the picture, how you leave the picture or enter it.

In another way the band is a point of reference. These works have this curious inside out characteristic. What is emphatically surface is the surface of the depicted landscape. The most clearly literal surface is the surface of the picture — of the icon. This is odd since there is a lot of ‘literal’ (non-pictorial) paint spread across the surface. But this latter is read iconically or figurally. The iconic is rendered somehow literal, the literal somehow iconic. The band is caught - oscillating between a pictorial device and a ‘literal’ surface. It is, as it were, out of control figurally and literally. This shifting instability of landscape as icon, ‘paint’ as icon, landscape as literal surface, and so on is not an immanent property of the painted surface(s). It seems in general that the disturbed paint integrates the ‘abstract’ band into the icon to a very considerable extent. So you don’t in fact get a melange of a ‘modern’ (abstract) painting and an ‘old’ landscape painting, what results is a continuous pictorial entity. At the same time that continuous pictorial entity is rendered literal by that which makes it a continuously pictorial entity. In other words there is a torsion almost to the point of a self-contradiction. The disturbed paint makes a continuous ‘icon’ of the landscape and the band, but that icon is, in turn, relatively more literal, it is the literal surface of the painting. The disturbed paint is relatively more of an iconic psychological presence than the landscape and the ‘wall’ itself - they are the ground for the figure. There is, if you like, a folding up or crumpling such that one’s sense of the iconicity of the landscape is hidden or folded within one’s sense of the iconicity of the disturbed paint.

MR: We didn't plan these complications in advance, we didn’t know they were going to happen. The band had a decisive effect on the paintings. It first added ‘weight’, and then a sort of tension. (Some of this has to do with unpicking what it is like to make them.) There is a tension between one’s psychologically induced expectations and one's more philosophically reflective reconstruction of what must be there...

The highly pictorial landscape paradoxically becomes the most literal aspect of the paintings. This involves a sense of loss: the landscape is something which is lost, and is therefore more powerfully present. This is lost in a mechanism which it inaugurates — for which it is necessary and is necessary to it.

MB: It has to do with the imprisonment of the thing beneath the shiny unregenerate slab of glass. Without the glass there wouldn't be these possibilities at all. The glass renders the whole thing a sort of collage. Ail elements are made literal - made to be independently identified materials or things with independent significances and purposes. And in recovering a picture — an icon from the ‘collage’ - standardly pictorial items are materialised - rendered literal, the literal pictorial and so on. Remember, however, that this ‘independence’ is virtual not actual.

It also has to be remembered that there is an archaeological relationship between the ‘disturbed’ element (the smeared paint) and a small fragment of text. The mess under the glass is a deformation of four letters: s-u-r-f ‘Surf’ is an abbreviation, conceivably, for ‘surface’. It's also an abbreviation for nothing; it’s a Boojum word.

DB: It's also in that sense a Picasso word, like ‘Jour. . a which is conceivably short for ‘journal’ but also for a host of other words.

MR: The sense of loss, or of gain and loss of representation in these pictures is not all that far from the sense of gain and loss of representation you get in analytical Cubist paintings. The mechanism is quite different, however.

MB: I think you could more or less cogently argue that these paintings do reinvent collage as it might be understood in relation to the papiers collés of Braque and Picasso. This is in a sense distinct from the mere assembly of minor fetishes which undergo no transformation and are simply the props for deconstructive babble . . .

The intellectual challenge of being a picture is something now drowned in the noise of cultural calculation, This is roughly what I mean when | talk of the reinvention of collage. A collage is mere fetish if it is not fundamentally iconic ~ however hard that icon is to recover.

DB: We should probably talk more about the glass here. This is also both literally a surface and an iconic element in that through being indexically connected to the picture its various properties, which include its reflectiveness, become properties of the picture. These reflections seem to become another kind of surface and space which intrudes on the landscape.

MR: You are never at rest in that respect. The glass introduces particular problems when the pictures are being photographed for reproduction. They always look theatrical if they include reflections. The problem is they always have to be staged for a photograph. The point is the glass is there to reflect, not to represent. You either have to leave reflections out of the photograph or take an installation shot. It’s possible to recover some of the literal significance of the glass from such a shot. A conventional reproduction with reflection would produce an icon of these reflections. In an oblique or installation shot you see them as connected causally to the reflectiveness of the glass.

MB: When I see a conventional reproduction, one without reflections, I always feel dissatisfied, but I also recognise that it is intellectually necessary that the reflections be obscured in this form of reproduction. A literal representation would be or would entail a misrepresentation.

MR: This is the point at which the paintings almost live in the worid of sculpture. If you photograph a sculpture you know it is incomplete: you know that if you move to another position you will see something completely different. And sculptures usually have to be photographed in some kind of ‘real’ space.

DB: I remember Charles Harrison talked about the slablike quality of the pictures, which suggests another kind of sculptural aspect[3]

MB: This gives them a certain cultural edginess, they invoke minimal sculpture. Someone might argue that they are minimal sculptures with artistic tokens trapped in them – kitsch minimalism like washable Monet table mats. There is a kind of kitsch industry which is to do with trapping under a transparent and resistant surface something which is more opaque and fragile. I think these pictures skirt the margins of both kitsch and the soi-disant refinement of minimalism. Minimal art would no doubt claim for itself the condition of being the ultimate non-kitsch, inasmuch as it treats of real spaces and real volumes. it can be argued that the theatricality of the iconic elements in fact reduces the theatricality of the minimalist form so as to annul Michael Fried’s strictures.[4]

DB: To what extent was the glass put on in order to produce these kinds of effects and to what extent did you find these things began to happen in the course of trying to sort out something else?

MB: We originally conceived of the glass as covering only a part of the painting so as to permit certain sorts of extraneous ‘information’ to be placed rather contingently on and over the surface (of the glass). In other words you got a kind of scrape-off shop window — information’ which would not be culturally weighted in the same way that the original painting was.

DB: Which is precisely what glass is not meant to do when it is placed over paintings. It is meant to be pure transparency, it is not meant to interfere in these ways although it always does. Conceptually we try to suppress the noise generated by the glass almost as a kind of cultural reflex.

MR: We thought that if we placed a text on glass placed over the painting there would be a physical separation between the two surfaces. It would appear more as contingent information than as composition-with-text. Without the thick paint, on the other hand, it would be just a badly glazed painting. The glass works on the paint, but the paint serves to incorporate the glass into the picture.

MB: There were various ways in the previous series of Hostage paintings where we were courting certain sorts of high genre abstraction - courting doing it rather than doing it. We were working at the margin of psychologically ‘weighty’ abstraction and temporal disorder — the painting's becoming its unordered materials. The reflected surface might be a wall through which you saw parts of a museum: the painting as container for the painting-container. But the painting as container was the undoing of the icon-as- container it contained. It becomes the merely materialised presence of the icon it contains.

MR: The thick paint, as a palette and as painting becomes a kind of reversal of the museum, a reversal of the container and the contained. In this way it involved a disfigurement of the classical and persistent problems of figure and ground. A painting containing a museum, the materiality of the former being the iconic possibility of the latter.

MB: The glass in these later Hostages was the promise of a text. But if it was to be more than extraneous it had to put the painting at risk in some way, to do the opposite of what glazing is supposed to do. There had to be a cost in glazing the painting at alt, notwithstanding the fact that the glass was itself going to be papered and the painting obscured.

MR: When we first began to make these pictures we assumed we would have them framed. But if we had, of course, they would just have looked like conventionally protected pictures. They had to appear to be glazed in the studio rather than at the framer's shop. But the device does advert to various conventions of glazing and framing.

MB: The glazing provides a kind of temporality. We were still concerned with trying to find ways to solve the problem of the ‘future’ - the idea of time-yet-to-come. Given that it was possible to narrate a series of events as a real temporal structure, then the purely linguistic or textual modality of the future was not going to sit there in mere effacement or wilful gesture.

DB: I can see how this introduces a form of temporality into the work, but I'm not so sure how this serves to invoke ‘the future’.

MB: I don’t think you invoke the future. The future, as Arthur Prior points out, is merely possible.[5] There are conceivably some necessities for the future but these are only logical, or nomological. The merely possible is necessarily general, so you cannot invoke the future in the sense that you can evoke the past. In a way this goes back to one of the themes that was addressed by the snow paintings. One of the matters we addressed in those was in part a visceral matter and in part quite a difficult intellectual problem. It was how do you unpack the sentence ‘Something has happened to this painting’? Certainly, within the tradition which has been developed over the last 50 or so years, to narrate the difference between something’s happening to a painting and a painting’s merely being produced is actually quite difficult.

DB: A shot Leonardo? Or a broken Duchamp?

MB: The Large Glass is individuated in virtue of being broken and repaired, the shot Leonardo is not ~ it is individuated as a Leonardo, that is, in spite of being damaged and repaired. It’s this margin of ‘in spite of that seems interesting. There is one very instructive, very interesting and very bad painting, Pollock's The Deep in the Beaubourg. It is clearly a Pollock which something happened to: it had an accident; Jackson got desperate and painted it out but stopped at some point probably because someone came along and said ‘Ooh, that’s good’ or he fell over or whatever. The point is that it’s not a - painting that has literally had something happen to it but that you can’t in anything but pretentious dishonesty understand that painting without thinking of it as a painting that’s been subject to a disaster.

DB: The Pollock I thought you were going to mention was not The Deep but Out of The Web which is a painting that has had something happen to it perhaps for similar reasons but which has connected yet distinct layers of work on it.

MR: There are plenty of paintings to which something happens which just merge into a kind of a-temporal mess. The point about ‘something happening to it’ is that there is this dimension of narrative temporality. The Deep obviously had another coat but there are paintings which are assemblages which reduce that narrative possibility to a kind of (post?) modernist vernacular.

MB: There isn't the ‘jerk’ in it. There isn't the sense that noticing the happening is a potential derogation of the thing. The idea of being stalked by this sort of derogation has always more than fascinated us. The derogation is very similar in structure to the answer to your question ‘Why the landscape?’: the answer being ‘Because we produced a text’.

MR: And not ‘Because we are now landscape painters’.

DB: Is this not the core structure of these works and others before? The text generates the landscape which as it were eats the text; the landscape produces and is in turn derogated by the band; the disturbed paint qualifies and rearranges that distinction, the front surface of the glass does further damage to what's there so far; the text which you have applied to one or two of the pictures does its work on the front surface of the glass; and does your malapropisation of the text serve to derogate that act?

MB: Each stage or process is successively a resonance in the guts of the last bronze god.

DB: There is an irony there, I suppose, in that from the iconoclastic blow of Conceptual art another idol was formed. Although this process was not invented by Conceptual art: Duchamp’s Urinal is the most obvious example of idolised iconociasm.

MB: Each moment imposes a very powerful moral strain on the subsequent moment. This is precisely why the matter of the future was simultaneously so repellent and so beguiling - for its cultural didacticism, but also for its psychological, moral and emotional intricacy. I don’t think you can interpret these ‘landscapes’ adequately unless the genetic character of this textual material is recovered.

MR: We don't mean by that, that we would like to resurrect Conceptual! art, but I think running through the work is the conversational base which Art & Language started out with. It is this morale, not stylistic trappings, which runs through the work. The landscape is there, but it is a face, a face we were forced to pull.

MB: The point is that we moved from the text to the landscape immediately, without the intervention of years. The problem was an artistic one, not a theatrical one. We are in the business of representation. We are not the impresarios of literal theatre.

MR: To some extent we are already in 1998 ... The compression of the moment when we were faced with actually painting this frightful landscape we had set for ourselves was very strange indeed.

MB: The original Hostage texts were themselves quite odd. Their power lay in their worthlessness, their value in their being realisable — that is, turned into falsehoods. As both texts and perlocutionary acts they were quite exotic. As bits of wood and canvas - as ‘form’ they were displaced to another time in our lives. In this respect they were quasi-pictures. I think the ‘landscape’ paintings with the poster stuck on produce similarly exotic tensions; one is in some way disempowered as a reader. That is, one is always at the edge of treating the text as iconic. You can imagine a picture in quotation marks - it's a fairly odd idea although quite an interesting one.[6] Can you also imagine a text rendered in the pictorial equivalent of quotation marks? It is made quasi-iconic – made near unreadable in virtue of its situation vis-a-vis the literally unreadable.

DB: Is not one fairly simple reason for this the fact that the text has a physical presence, it isn't pure text but a thing, an object which acts physically on the work, which gets in the way of looking at other things?

MB: Yes, but there are other paintings in which we have introduced large areas of text (two of the Museum paintings and a related print) that have a rather different pictorial effect. These were all more or less literal texts. The difference seems to have something to do with the fact that they share the same surface. In these current paintings, the intervention of the glass means the text does not share a surface, it covers one. Importantly it also covers up a picture. The mind resolves this loss, by trying to force the edges of the texts into the pictures.

MR: When you look at the text on the front of the picture you are made quite aware that the thing you are reading is obscuring something you might rather not have obscured. But it is not obscuring it in the same way as it might if the poster was applied directly onto the paint. In these the poster has a shadow behind which you might try to rummage.

MB: it is a ‘something that’s happened’ to the picture. A text slapped on the surface would be something more like the realisation of the painting. It’s harder in the former case to identify the aesthetic target. And I think you try to integrate the text into a plausible space within the picture. You tend to read a line, then your eye strays off in order to set it spatially somewhere. You constantly try to readjust the text in a non-reading way. You cannot read and look at a scene simultaneously. Your attention is split, rendering you, so to speak, both verbally and visually dyslexic. This means the text hovers in some strange purgatory between being iconic and non-iconic. It is so far towards the limit of what could conceivably be iconic.

DB: Given the degree to which the text-poster is tied in to the structure and narrative of the work, some viewers might be surprised not to see them on more than a fifth or a quarter of the pictures.

MB: The text is perhaps always a derogatory possibility which the paintings face but which they do not all have to wear on their faces. The loss that's involved has to be from the ‘outside’ as it were rather than an internal stylistic convention. If we stuck a text on every painting it would become not an act of derogation of what's beneath but a device of quickly diminishing power.

MR: The danger of the texts is that you risk losing the textual quality of the paintings. It’s important not to lose the sense of there already being a text in the painting, albeit archaeologically.

MB: This suggests to me a connection between these paintings and many of your other pictures. The processes that you have described by which various elements of the work are made to act upon each other are visible in some of your earliest paintings such as the Portrait of VI Lenin in the Style of Jackson Pollock series. In these you set up your abstract expressionist style and you set up your socialist- realist element and they were made simultaneously to derogate each other.

MR: This is what made them not post-modern. There was always a baroque confrontation between one and the other. In ‘post-modern’ art you set up your clash of images, and perhaps leave the dogs to fight, but there is never a moral loss, the onlooker doesn't get involved in the scrap.

MB: One of the more memorable observations made to us recently was by someone in New York who said ‘It's so interesting that in relation to your earlier work you have become so lyrical’. At some point I have to regard that statement as first order. The displacements in the work were successful enough to direct that person into a 180 degree (mis)interpretation. That (mis)interpretation is as it were one of the ironies internal to the work. The attempt to produce a stable, non-radical, non-sceptical, non-ironic, non-self-inconsistent interpretation of the work must be doomed to failure, or the work has failed. This is not charismatic solipsism. The work requires the prosecution of conflict, not the luxury of the play of contrasts. This conflict may always remain ordinal. You may never get a sense of the whole. This is reality - the only chance against manipulative barbarism. The ontological problem is that a work of art tears itself apart having worn the clothes of ‘unity’. Adorno’s interpretation of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis is entirely germane.[7] | think we can extract more hope than Adorno, I don't think I have to resort to quite the same artsy pessimism as he insists upon. The radical incompleteness of what he called the human project, the necessity for the radical interpretation at any and every moment in the unfolding of that project, and therefore the dry necessity of taking risks ' with aesthetically uncomplete and self-uncompleting works, is what hope there is for a human project. This is entirely distinct from the solipsistic play of contrasts authorised as a secure Cultural moment. That’s Tony Hancock.

Notes

1 See Charles Harrison, ‘On the Surface of Painting’, Critical Inquiry, vol 15, no 2, Winter 1989. See also chapter 7 of Harrison, Essays on Art & Language, Blackwell, Oxford, 1991, PpP175-200, which is based on the same essay.

2 See ‘Frames’, written, directed and produced by Gina and Jeremy Newson for Signals, Channel 4 TV: broadcast 15 February, 1989.

3 Charles Harrison, '“Form” and “Finish” in Modern Painting’, paper delivered at Form conference, Slovenian Society for Aesthetics, Yugoslavia, October 1990. To be published in Journal of Slovene Academy of Sciences, 1991.

4 Michael Fried, ‘Art and Objecthood’, Artforum, June 1967. Reprinted in Minimal Art – A Critical Anthology, ed G Battcock, Dutton, New York, 1968, pp116-47.

5 See AN Prior, Time and Modality, Oxford, 1957.

6 See, for example, Nelson Goodman, Languages of Art, Harvester Press, Brighton, 1981.

7 Theodor Adorno, ‘Alienated Masterpiece: The Missa Solemnis’, 1959, in Telos, no 28, Summer 1976, pp113-24.