Life Drawing: Ann Temkin

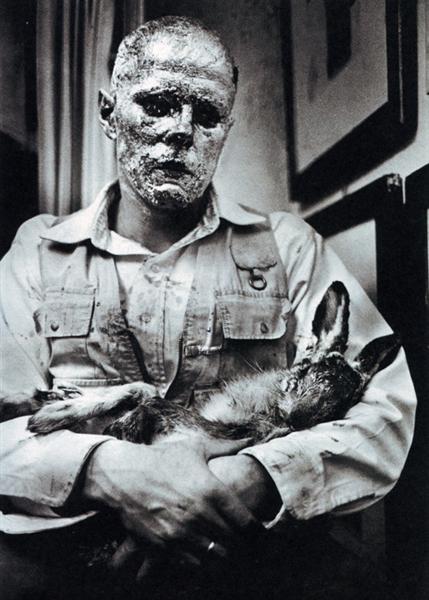

Galerie Schmela, Düsseldorf, 26 November 1965

One of the best-known images of Joseph Beuys presents the artist seated in an art gallery, dressed in jeans and fisherman's vest, cradling a dead rabbit in his arms. Beuys's trademark felt hat, synonymous with the artist himself, is missing; instead his head is coated with honey and gold leaf. Behind the artist a group of large drawings hangs on the wall, their thin lines almost invisible in the photograph. The year is 1965, and the setting is the action How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, which Beuys performed at the opening of his first exhibition at the Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf. The pictures in question are Beuys's own drawings, crudely framed and densely hung.

This striking photograph exemplifies the place of drawings in Beuys's work: always in the background, they provided an essential basso continuo to his other work. Autonomous objects in themselves, they are an inextricable part of the Gesamtkunstwerk of Beuys's life, teaching, performance, sculpture, and political activism. The total number of Beuys's drawings is unknown, but it is generally agreed to exceed ten thousand sheets. Beuys has been described by those who knew him as constantly drawing; he drew while traveling, while watching TV, while in private discussion, while in performance. Beuys's attitude toward drawing implied it to be as intrinsic to him as breathing.

The photograph of Beuys and the hare demonstrates rupture as well as continuity. Beuys's performance at the Galerie Schmela marked the conspicuous beginning of the second half of a four-decade career. During the next few years Beuys emerged as a leader in an international vanguard convinced that art-making could not be separated from the sociopolitical context in which it occurred. Paradoxically, the moment at which Beuys's work began to be embraced by galleries and museums was the point when that work (and that of a new generation of artists throughout Europe and the United States) began to challenge the authority vested in such institutions. Innovations in medium and structure signaled rejection of modernist ideas of art's permanence, transcendence, and form itself.

The pictures that Beuys "explained" to the hare were, by that point, a sort of work that engaged him far less powerfully than previously. Drawing had been Beuys's major preoccupation throughout the 1950s; during the mid-1960s his drawing practice markedly shifted to become a vital component of the performance and activism that characterized his next decades. Yet Beuys always insisted that those early pictures contained the seeds of his later use of drawing as a vehicle for social change.

Beuys's rhetoric with regard to his early drawings was remarkably consistent over the years in the course of innumerable interviews. He referred to them as the source of all his ideas, and as catalysts to his work in all mediums[1]. Beuys made this assertion in respect to drawings that appear to be self-sufficient "presentation drawings" as well as to those that seem to be note-like jottings. The importance that Beuys attributed to his drawings is consistent with the autobiographical voice of his work as a whole; drawings traditionally are regarded as the work most intimately connected to the artist, as is implicitly acknowledged when scholars examine a sketch book much as one would a diary, or use drawing as a key tool of connoisseurship. Beuys's estimation of drawing relates both to the medium's distinguished place in the German artistic tradition, and to its importance in the line of modernism – stretching from Marcel Duchamp and Dada to contemporary conceptualists – that valorizes idea rather than masterpiece.

Beuys was extraordinarily voluble during the interviews and lectures that filled the last two decades of his life, as critics, collectors, journalists, and curators sought explanations of his work and ideas. The gathered pages of published and unpublished interviews would run into the thousands, not including the innumerable hours he spent talking in the classroom, following an action, or at an exhibition. Only in extremely rare cases, however, did Beuys directly address the subject of the art he made. While he was willing to speak volumes on his theories of art and society, he displayed great reticence when it came to the matter of his art objects.

A valuable description of Beuys's drawing exists in the form of a telephone conversation in 1974 with the art critic and historian Caroline Tisdall on the occasion of the exhibition of his drawings entitled The secret block for a secret person in Ireland. This "conversation" was transcribed in the catalogue published by the Oxford Museum of Modern Art[2]. The text demonstrates Beuys's frequent use of the telephone to express the idea of communication, but it also rather coyly plays down the seriousness of the exchange, placing it on the level of a chat rather than a lecture. Beuys's pleased conclusion to the published version of the "conversation" was: "See we have talked for two hours and not said one word about art."[3]

Beuys's language of drawing is open to enormously rich possibilities of interpretation. The process of separating the important strands that inform his work — alchemy, the Christian tradition, anthroposophy, folklore, literature, and the history of science – reveals the extraordinary breadth of the thinking that underlay the methods of Beuys's art[4]. Beuys's drawings invite individual reading to a degree unique in the work of his contemporaries. Here, however, the place of drawing will be situated within Beuys's career as a whole. Through a study of his drawings, one follows Beuys from his position as an isolated outsider, to that of the avant-garde teacher and performer, to the "social sculptor" intent on worldwide reform. Over the course of four decades, Beuys's drawing moved from the sketchbook page to the blackboard, from private to public; the studio and the gallery were replaced by the street, art fairs, magazines, and television. The lone dead hare metamorphosed into thousands of students, collectors, activists, artists, and tourists watching and listening to Beuys explain his vision.

Beuys's drawings, like his entire oeuvre, participated in the formation of the artist's identity. Beuys has been suspected, with Andy Warhol, of being more noteworthy as a celebrity than an artist, but that judgment ignores the fact that Beuys's construction and presentation of self occurred inside his work rather than outside of it. His life and work have an intrinsic and reciprocal relation in which priority is undefinable: the artist "Beuys" is as much a product of the work he created as that work is a product of "Beuys." The unique conflation of life and art expressed in that signature became the vehicle through which his work found its voice, and through which it continues to speak today.

(Stoop) if you are abcedminded, to this daybook, what curios of signs (please stoop), in this allaphbed! Can you rede (since Weand Thou had it out already) its world? (James Joyce, Finnegans Wake)[5]

Beuys's unusually long formative period prior to recognition as a professor and an artist in the early 1960s evolved through the medium of drawing. A vast body of work on paper pre-existed the emergence of the public figure who came to be known as "Beuys"; a recent exhibition of the early drawings was aptly entitled "Beuys before Beuys."[6] The painfully precise and delicate lines of these mysterious drawings convey Beuys's search for an alternative language, his escape from "the usurpation of language through culture development and rationality."[7] The alingual communication he advocated with the hare in his arms can be seen as the original objective of the drawings themselves. Beuys's initial interest in art had its source in the question of language. Beuys listed in his Life Course/Work Course for 1950 "Beuys reads 'Finnegans Wake' in 'Haus Wylermeer'" (a cultural center near Kleve)[8]. Beuys singled out a book that expanded the limits the English language had posed for its author (Joyce had informed skeptical friends that he was at the end of English[9]), and that created a rich network of multilingual puns to provide a new vocabulary. Joyce's revolutionary concept of language assured him a place in the pantheon of personal heroes from various centuries and disciplines whose biographies Beuys artfully braided into his own through out his life[10].

After Beuys left the Düsseldorf Academy in 1951, he commenced a period of isolation that resulted in one of the most remarkable outpourings of drawing in this century. Beuys spent close to a decade elaborating a personal idiom, doing so almost entirely in the medium of drawing. Setting aside the functionalism of academic training, he sought in his drawing practice an avenue to other realms of the spirit. Working in solitude in Düsseldorf, Beuys drew prodigiously: thousands of works on paper in oil, watercolor, and ink and pencil record the themes and ideas he was investigating. The intensity with which Beuys worked during these years finds few equivalents in the art of his predecessors. The analogies are to periods of crisis; one recalls, for example, Paul Klee's last year of work, achieved both despite and because of physical and spiritual agony[11]. For Beuys these years were a therapeutic episode; in fact, he was administering to himself what in 1964 he would call the "Art Pill," which by then he directed at the healing of society as a whole. Beuys later referred to the decade of the 1950s as a long period of "preparation," evoking the mandatory period of purification for holy figures in many religious orders as well as tribal cultures[12]. John Cage once stated that art must serve as self-alteration rather than self-expression; this process might best describe Beuys's explorations during the 1950s[13]. Like the burrowing hare, the artist went underground.

Beuys had been drawing since boyhood. Landscape near Rindern, 1936, one of the few surviving watercolors he made during high school, faithfully portrays the flat, spare landscape of the Lower Rhine area. Beuys continued to draw during the war, and as a student at the Düsseldorf Academy, he adapted his work to the idiom of his professor, Ewald Matare. Matare's artistic language reconciled abstract form and naturalistic figure, and his students followed his example in sketches of plants and animals structured in geometric sections. The small wooden and bronze animal sculptures made in class share the simply articulated forms of these studies. Matare's sensitivity to any material's inherent qualities was one of his more important lessons for Beuys, as can be seen in remarkably textural drawings such as Sheep Skeleton, of 1949[14].

Beuys's earliest drawings also made direct use of Christian symbolism, which in more subtle ways would permeate his work throughout his life[15]. Drawings from the years 1948 to 1951 include many renderings of the Pieta, the Crucifixion, the Man of Sorrows, and the Lamentation. These belong more to a process of private exploration than classroom mandate. Beuys later described works such as these as "small attempts" to approach the spiritual realm in terms of traditional motifs[16]. In many of the drawings Beuys sought to integrate Christian imagery into a broader context, setting the religious element in a cosmic, nature-based frame recalling the pantheism of German Romanticism. The drawings are contemporary with many small crosses he sculpted in wood and bronze, reminiscent of ancient relics, which thereby add a pagan aspect to a Christian context. For example, the bronze Sun Cross, of 1947-48, points to the ancient significance of the cross as a sun symbol, as it conflates the crown of thorns around Christ's head with the form of a sunburst.

During his years at the Düsseldorf Academy, Beuys and several fellow-students developed an intense interest in the interpretation of Christianity espoused by Rudolf Steiner. Beuys adopted from the anthroposophist what he later termed "the fundamental anthropological notion of the human being . . . the human being as a being that has a thoroughly earthly character and yet cannot be described without a transcendental dimension."[17] Steiner's teaching on the unity of the spiritual world with the physical world directly influenced Beuys's imagery, as did his emphasis on the event of Christ's Resurrection as the pivotal moment in man's spiritual history. Beuys's delicately penciled Cross of 1950, corresponding to the bronze Throwing Cross of 1949-52, imparts to the cross the quality of a living thing as it conflates monument and blossoming plant; the cross implicitly signifies the transformation and hope that follow suffering.

The spiritual quest manifest in these drawings continued into the decade of work after Beuys left the academy in 1951. Drawing became the vehicle for that search and, at the same time, a way of life. The countless pages, ranging from simple writing paper to small sketchbooks to torn sheets of newsprint, testify to one large work in progress. There is a strong dichotomy between the narrowly defined range of key themes, such as the female figure and the landscape, and the mesmerizing variety of renditions that continually renewed the encounter between the artist and the page. This introspection differentiated Beuys's work from the art of the day, and his drawings bear little resemblance to contemporary German artists' echoes of Expressionism or experiments in abstraction. The archaic motifs and the drawing style maintain a powerful, if puzzling, anachronism. Yet Beuys's desire to step out of time and place reflects his position in a context that offered no real sense of either. During the 1950s German culture had yet to recover its foothold from more than a decade of Nazi dictate; German identity was being questioned, as collective ambivalence over the recent past effectively blocked access to an older tradition.

Internationally, too, the postwar years sent scores of artists seeking models that offered an alternative to contemporary bourgeois culture. Abstract Expressionists in the United States turned from shattered illusions to the realm of primitive myth. The "anti-cultural position" of the Frenchman Jean Dubuffet condemned a Western culture too fond of analysis and argued for painting that could "imbue men with new myths and new mystiques . . . ."[18] Beuys's therapeutic ambition was distinct, nonetheless, in its specific investigation of the roots of a poisoned Germanic tradition. His effort to transcend the present excavated a vision of the past he would later use with the aim of changing the future.

The female figure pervades Beuys's drawings of the 1950s: the world of these drawings is one almost empty of men. The many artists who portrayed women so constantly —Auguste Rodin, Gustav Klimt, Alberto Giacometti, to name three who interested Beuys — had differing contexts for their obsessions. In Beuys's case, the insistent representation of the female figure over the course of a decade in hundreds of sheets suggests a personal search for the qualities embodied in the traditional feminine archetype. As a ruined Germany initiated its "economic miracle," Beuys sought recovery in the opposite direction. Setting himself up as an outsider to society —a patriarchal society —this litany of women points toward an alternative: an ease among the spirits and nature, at far remove from civilization.

Throughout the 1950s Beuys's drawings of women grew more technically sophisticated and diverse in mood, but the pattern was established with the simple figures of the late 1940s. Most often, the woman represented is isolated on the page, self- absorbed and self-contained. The depictions of the 1950s were steeped in tradition, as witnessed by several images of the theme of Death and the Maiden. The figure is seldom individualized, even in the case of an occasional portrait (minimally identified by initials), or an historic or mythic figure such as Judith or Diana. Generally, the features of the face are unimportant, and sometimes the head is not represented at all, such as in Nude, of 1954-55, where the woman's shoulders meet the top of the page. More notable is the sculptural carriage, an acrobatic reach, or a graceful gesture. The placement on the page is the most dramatic aspect of these quiet works, as the figure hovers in a void or balances provocatively at the edge.

Beuys's images present an essentialist view of woman as a sign for the natural world, and, at the same time, the realm of the spirit. Whether seer or mother, priestess or acrobat, she occupies the axis opposite from intellect and culture. Haunting images such as Woman Warding Off, 1952, perpetuate the ancient concept of woman's connection to the irrational and immaterial. Attention focuses on the woman's staring eyes (covered by hands in the fainter visage hovering above), while a tiny spiral (which Beuys considered a "hearing form"[19]) suggests his equal interest in the ear as an organ of perception. The extraordinary perceptive powers Beuys ascribed to his women set them in the tradition of the ancient sibyls, who preserved the link to the gods long lost by the general community. In certain nomadic societies, male shamans wore women's clothing in order to establish contact with the spirits. Carl Jung discussed such practices as demonstrations of the anima, the feminine personification of man's unconscious. Jung's portrayal of the anima principle as a "radio" to man's unconscious anticipates Beuys's later description of himself as a sender or a transmitter, the intermediary between the spiritual and earthly worlds[20]. Beuys would articulate this feminine capacity in later works such as the multiple of 1968 entitled Intuition — a recommendation in the form of a word penciled on a wooden box.

Simultaneously, Beuys's female archetype claimed a connection to the earth, an association with seasonal cycles and growth. Beuys's drawings of the 1950s include many images of pregnant women and women menstruating or giving birth. Beuys also focused on the state of motherhood, in straightforward pictures of mother and child as well as in more mysterious works such as the drawing Mother with Child, in which two figures loom over a railway landscape, cradling a child between them. Conversely, women are sometimes depicted as strong warriors sporting spears or shields. Many, such as Representation with Critical (-) Objects, 1957, portray women with strange objects in the forms of filters, rolls, or wedges that anticipate Beuys's sculptural forms of the 1960s. The women's mobility —spiritual as well as physical —is implied by the many wearers of skates or snowshoes, or more exotically, a female astronaut.

Beuys extended the idea of the natural woman in drawings such as Woman Sitting on the Ground, 1952, in which women assume almost animal-like positions. Sometimes the visual pun is explicit, as in Bat, 1958, where the spread legs of the woman become wings. Beuys's many depictions of women as basket-makers or carriers signal their own biological capacities as vessels. Indeed, the women often appear as vessels, their graceful forms drawn as those of an amphora, or the area of the womb explicitly depicted as a cavity.

The figuration of the female provided Beuys with a vessel for images of otherness, as it had for generations of male artists before him. In this respect, a solidly traditional cultural viewpoint coexisted with the radical aspects of his work. Woman already offers a representation of an Other, from a male point of view. This duality is replayed in the female's own dual characterization, at once ethereal and/or natural. Predecessors such as Paul Gauguin or the German Expressionists had represented women as fleshly creatures set within the faraway culture whose otherness they embodied. Beuys's vision pointed north, but whereas he occasionally identified a figure as Eskimo or Tatar, his women generally remain immaterial, often almost ghostly. The quality of absence on these pages gives them their poignancy as well as their capacity to function as signs; the lack of solidity, of identity, and of setting is filled by femaleness.

Beuys's exploration of medium is the most important vehicle for his emphasis on the organic aspect of woman. The female figures are evoked in many mediums, ranging from all sorts of pencil line (faint silhouettes, intense networks of nervous scratches, exquisitely shaded plastic volumes) to almost transparent watercolor and thickly painted oils. At the end of the 1940s, Beuys painted the female figure in delicate pinks or pale green watercolor evocative of Rodin's example. Soon thereafter Beuys derived the use of what was probably an iron compound in solution often referred to as Beize, the German word meaning stain or corrosive, and the general term for furniture wood stain.[21]

Beuys reserved this medium primarily for depictions of women and girls, and used it for the rest of the decade. The iron medium refers to the female in substance as well as in form and relates closely to the hare's blood with which Beuys also worked occasionally, as in Color Picture, of 1958. Depending on the intensity with which it is concentrated on the page, Beize produced colors varying from a warm honey to a rich red brown. Beuys often used a thin onion-skin paper for works painted with Beize, so that a pronounced puckering surrounds the saturated area. The solution permitted Beuys a rich exploitation of positive/negative space in delineating the human body. In works such as Untitled (Salamander I), 1958, the medium impregnates the sheet and pools in sculptural ponds of varying shades. Saturated with this solution, even more than in Beuys's watercolors, the page itself becomes a vessel for the liquid medium.

The female figure suggested for Beuys a bridge between the earthly and unearthly worlds. The animals that populate scores of his drawings of the 1950s function in the same way. In Matare's classes at the Düsseldorf Academy, Beuys had drawn animals in the manner of his instructor, but after 1951 both his iconography and idiom underwent a dramatic shift. The local world of farm animals such as sheep shifted to the realm of Northern legend, while strictly geometric analysis of form gave way to individual freehand drawing. Beuys elaborated a specific menagerie of swans, stags, elk, and bees, all dense in symbolic meaning, Germanic as well as Celtic, Christian, or Greco-Roman. These are animals of legend and folktale; although they occupied the Northern landscape, it is their mythical powers more than their physical presence that fill these drawings. Beuys described these animals as "figures which pass freely from one level of existence to another, which represent the incarnation of the soul or the earthly form of spiritual beings with access to other regions . . . ,"[22] The reference could describe Beuys's hopeful vision of himself at that moment; indeed, it defines the aspirations of the Romantic artist from Caspar David Friedrich to Wassily Kandinsky to Clyfford Still. Friedrich 's paintings of figures standing on mountaintops explicitly posit the artist as mediator between the earthly and otherworldly; the prevalence of mountain imagery in Kandinsky's and Beuys's work echoes that shamanistic or priestly identification. And just as animals provide shamans with their attributes, so they serve an artist who casts himself as such a mediator.[23]

The animal most closely identified with Beuys is the stag, a traditional emblem of the Northern forest and an omnipresent creature in German legend. In Beuys's work the stag assumes particular meaning as a spiritual being ("accompanier of the soul"[24] a status shared in many folk and religious traditions. In Celtic legend, for example, the stag is the spirit guide, and in Christian tradition, a symbol of the crucified Christ.[25] The stag is a conventional symbol of masculine power, but it also has a feminine aspect as a symbol of fertility, with antlers that are renewed each late autumn or winter and fall off blood-red every spring. The figures in drawings such as Stag, 1955, have a princely mien and yet the exquisite grace of feminine beauty. The stag appears in scores of Beuys's drawings of the 1950s, in a wide variety of pictorial formats. In many pencil drawings the animal is formed by a thin and fairytale line, while in others the stag is conjured out of thick pencil that has the roughness of charcoal.

Beuys's stags or elks often assume a martyred aspect and appear wounded or as skeletons. These lonely scenes are easily read as tales of spiritual defeat; Beuys discussed the death of the stag in his drawings as "the result of violation and misperception."[26] Such scenes relate to the many images of the skull in Beuys's work of the mid-1950s. Whether modelled in pale watercolor or detailed in networks of radiating pencil lines, the skull suggests hardened thought —necessarily softened with honey in order to "explain pictures to a dead hare". Often shown on an "ur-sled", the skull is presented as an intermediate stage in existence, passing from material death to spiritual rebirth.

Beuys commemorated the death of the stag, in particular, in a number of striking pencil drawings from the 1950s called "stag monuments." These images all present a large sculptural form whose arching pyramidal shape loosely echoes a stag's skull, the volume defined by fine striations. The stag monument remained an important element in Beuys's symbolic landscape throughout the rest of his career — in 1978 he confessed it to be "still in his head"[27] — and his sculpture Lightning with Stag in Its Glare, 1958-85, endures as its final grand memorial.

Beuys's most personal totem is the swan, the traditional symbol of his native town of Kleve. To this day a Swan Tower crowns the town's center, honoring the legend of the swan who delivered the knight Lohengrin to the daughter of the Duke of Kleve.[28] In countless forms, the swan occupies a central place in Norse and Teutonic myth, legend, and folktale —generally as a feminine force linking the realms of life and death.[29] The swan first appeared in Beuys's drawings in quite naturalistic guises and thereafter in far more abstract drawings where a fluid sweep of line alludes to the grace of the bird and the ripples of a lake.

Beuys's expansive, lush line, executed variously in lead or colored pencil or inks, is at its best in a family of works known as "From the Intelligence of Swans". Again, Beuys's title refers to the realm of knowledge that lies beyond simple human intellect. The swan's "intelligence" implies its connection to the other world (heralded in the Lohengrin legend as well as in the common notion of the "swan song," a swan's announcement that it is to die). A mediator between different realms, like the stag, it also mediates between the sexes: its essentially feminine aspect is united with a phallic neck. The swan embodies the unity of the female and male capacities in a single being, the integration of physical prowess and psychic powers.

"From the Life of the Bees" is a group of works parallel to that of "From the Intelligence of Swans." Neither is a series as such; both groups include drawings made over a long span of time, with a wide variety of mediums and sup ports. While the bee did not share the local specificity that the swan had for Beuys, it is a creature that has attracted fascination for centuries and was considered divine in many ancient cultures. Beuys's title repeats that of the well-known book The Life of the Bee, written by Maurice Maeterlinck in 1901, but Beuys's more direct inspiration was probably his reading of Rudolf Steiner's lecture "Uber die Biene," given in Dornach in 1923. Steiner emphasized the importance of the bee's process of forming solid geometric shapes (the honeycombs of six-sided cells) from amorphous material (the bee's waxy secretions), a metamorphosis he saw as parallel to those that take place continually in the individual human body as well as in the earth itself.

"From the Intelligence of Swans" displays the virtuosity of line in Beuys's drawings of the 1950s; "From the Life of the Bees" presents the role of substance. While draw ings such as the Queenbee (For Bronze-Sculpture) , 1958 , employ a regal gold, most of the bee drawings are made in the honey-colored Beize solution that Beuys used for his female figures. The connection recalls the ancient identification between the queen bee and Venus, and several of Beuys's early sculptures and drawings conflate the form of the bee and woman, such as the tiny Woman, of 1957. The honey color and oozy quality of the Beize solution medium evoke what Beuys called the "warm" character of the liquid the bees produce and transform into a geometric structure.

This counterpoint between "warmth" and "cold," between organic amorphousness and geometric form, provided the foundation of what would become, by the end of 30 the 1950s, Beuys's theory of sculpture.[30] His elaboration of the process of metamorphosis has as its exemplar the activity of the bee, and the honeycomb offers a natural model for Beuys's "fat corner," the sculptural form that integrates fluidity and geometry. The bee's waxy secretion has a chemical composition similar to that of fat, and the long history of wax sculpture was an important antecedent to Beuys's seemingly radical choice of medium.

Beuys was well within tradition when he used the bee as a basis not only for sculpture but for social sculpture. The bee's advanced social organization —long praised as a model of perfect order and industry by societies ranging from the medieval Catholic church to nineteenth-century Utopias —provided a pattern for a social sculpture wherein individuals are integrally linked in self-government. Even more directly than the drawings of animal or female figures, the sheets on the theme "From the Life of the Bees" hint at Beuys's transformation of a visual motif into a conceptual system and of a personal vision into a universal one.

The animals and figures in Beuys's drawings of the 1950s inhabit an undefined region, affixed neither to heaven nor earth. Similarly, the landscapes he painted and drew during this time were curiously placeless. While Beuys's early watercolors mir ror his native countryside of Northern Germany, and works of the 1940s document the places he saw during the war, the landscapes of the 1950s rarely portray a spe cificview. These landscapes have more to do with process than with place, as they pictorialize the drama of creation and regeneration. Beuys's subjects —glaciers and volcanoes, waterfalls and mountains —chart the formation of the earth in primeval times and its continuing evolution. They represent the carving of space and the shaping of land that occurs over the ages. Rarely are there inhabitants or other evidence of civilization; instead, the earth appears as a sculptural site that natural processes endlessly create. Beuys often made this concept literal in drawings such as Warmth-Sculpture in the Mountains (Double), 1956, in which he placed "sculptures" within the landscape.

The interchange between solidity and fluidity that occurs during these earthly processes supplies the poignancy of the sensuous watercolors Beuys painted during his months at the van der Grinten farm in 1957. In all of these drawings —themselves solid objects —the vitality of water is foremost, whether mixed with pigment or present in such forms as tea or berry juice, which Beuys sometimes used as mediums. Certain drawings depict water processes specifically, as in Two Reflections on the Water, while a work such as Granite takes as its subject a hard crystalline substance that originated as molten liquid. Both in subject and technique, Granite and a host of works like it explore what Jean-Paul Sartre described as "the secret liquid quality in solids," evoked in Grimm's tale about a tailor who pretends to draw water from a stone, using a piece of cheese to accomplish the trick.[31]

Beuys's watercolors explore the theme of creation and metamorphosis. The cyclical nature of life (Joyce's Finn again awaking) and the pattern of birth and rebirth underlay Beuys's spiritual vision. And whereas Beuys was not engaged in confessional drawing, these subjects reflected Beuys's unmistakable response to his current situation. The drawings posit the re-creation of a country — both a landscape and a culture —that had undergone a collective death. They document the creation of an artist who needed to be invented and forecast an art whose very subject was to be creativity.

By the end of the 1950s this art began to take form in what Beuys described as a purposeful integration of the realms of science and art. Naming as his models the universal thinkers Leonardo, Paracelsus, and Goethe, Beuys sought to merge the paths of spiritual, intellectual, and artistic research. He later remarked that by 1958 he had begun to be convinced "that the two terms, art and science, are diametrically opposed in the development of thought of the Occident, and because of this fact, a dissolution of this polarity of perception had to be looked for."[32]

The initial sign of this search was the variety of scientific allusions in Beuys's pictorial language. Beuys was widely read in science, dating back to his early plans for a career in that field, and his imagery at the end of the 1950s reflects this interest. Beuys's plaster Aggregate of 1957, which was cast later in bronze for works such as Double Aggregate, 1958-69, parallels drawings that depict electrical apparatus such as batteries and inductors.

The theory of sculpture that Beuys developed at exactly this time also resembled a scientific formula: the "warmth theory" recognized that heating and cooling were the active factors in changing mass and proposed this thermal axis as the basis for the making of sculpture. It doubled as a formulation for the thinking process — opposing dry, dead, "cold" thought with fluid, living, "warm" intuition. This oscillation is the basis of countless drawings made between 1958 and 1961, many of which are Beuys's most powerfully mysterious images on paper. In these graphic works that have no definable subject and yet are far from abstract, the energy of Beuys's line was more highly charged than ever before.

Relatively few pencil drawings from this period now exist as autonomous works. Among the most elaborate is the drawing entitled Currents, 1961, in which arrows pointing up and down chart the energy forces within a complex tangle of ducts, channels, and waves drawn on a long, narrow sheet of tissue-thin paper. More typically, Beuys worked in sketchbooks and preserved in distinct masses the draw ings that explore his theory of sculpture. The four sketchbooks collectively entitled Projekt Westmensch, begun in 1958 and continued through the early 1960s, include pencil drawings and watercolors as well as text notations.[33] Obviously a reservoir of plans and ideas, these books were preserved intact by the artist and exhibited only during his museum retrospective at Monchengladbach in 1967.

Many of the drawings of the late 1950s made on loose sheets or torn from sketch books were incorporated into the drawing project The secret block for a secret person in Ireland. Assembled and titled in 1974, the block consists of over four hundred drawings that Beuys said he had set aside over the years in order to form a totality. With three exceptions, the titles of the fifty-five drawings from 1958 and 1959 in The secret block are designated only by a line and a question mark (as Beuys told Caroline Tisdall, "Art is at its most effective and scientific when expressed with a question mark."[34]) They have as strong a sense of narrative content as his earlier landscapes —Beuys's collectors recall how the artist liked to "narrate" his early drawings, telling the story of each as he looked at them —but their iconography is less closely tied to existing tradition. The energy fields in these drawings conceptualize the sense of process and metamorphosis detailed in the earlier drawings.

The same enigmatic pictorial language dominates a series of six sketchbooks, known as the Ulysses sketchbooks, that Beuys worked on between 1959 and 1961.[35] These are indicated in the Life Course/Work Course by the statement for 1961 that "Beuys adds two chapters to 'Ulysses' at James Joyce's request." This elliptical refer ence indicates their profound importance to Beuys. The sketchbooks contain pages and pages of intensely worked drawings in pencil, crayon, and watercolor; containing 346 drawings altogether, they present an encyclopedic view of the artist's for mal and thematic vocabulary. The invention of language was again on Beuys's mind, and the drawings are the culmination of the long odyssey he made during the previous decade.

The signs and systems represented in these drawings defy verbal translation, yet they create a universe that is in itself somehow perfectly readable. In dense images full of arrows, canals, probes, and antennae, Beuys evoked natural processes of circulation, growth, and transformation. As one looks through the six sketchbooks, a variety of voices and moods arises in drawings more or less intense or quiet, all united in a flow that has no particular start or stop. The vitality of the line throughout the books attains a haunting level, as each point and stroke virtually moves on the page. Beuys understood Joyce's Ulysses as a spiritual book, and it is significant that he claimed it as a foundation for the drawings that gave pictorial form to the concepts of his warmth theory. He firmly maintained that his scientific pretensions were geared toward spiritual or evolutionary warmth, rather than anything actually rep resenting a technically scientific brand of art. In so doing Beuys reclaimed an idea with which he felt the twentieth century had lost touch: that the professional work of science, or art, was initially and ultimately a spiritual undertaking.

Interviewer: How do you relate to art, in general?

Beuys: My relationship with art is good. Likewise with anti-art.[36]

Beuys's emergence from a decade of self-declared "preparation" roughly coincided with his appointment to teach at the Düsseldorf Academy in 1961. At this time he discovered among the Fluxus artists working in West Germany an all-important laboratory for new forms and ideas. In a few years he would be the nation's most notorious artist, operating in a whirl of students, fellow-artists, journalists, and slightly later, collectors. Beuys had neither the need nor the time to give drawing the role it had during the 1950s, but it by no means disappeared as a central aspect of his practice.

This turning point is best witnessed by the appearance of the medium Braunkreuz (brown cross) in Beuys's drawings at the start of the decade. So named by Beuys, it is an opaque reddish-brown paint, varying considerably in tonality and texture in his different drawings. The use of Braunkreuz presents a distinctive change in the drawings, replacing introversion with an assertive voice in works often larger in dimension and more monumental in scale than those of the 1950s. From this point on, Beuys's drawing cannot be considered apart from the rest of his body of work. His art also began to resemble physically the contemporaneous work of German col leagues as well as American and European artists, and to engage ideas current among the avant-garde. Trespassing borders between drawing, sculpture, performance, and multiples, Braunkreuz provided an important route to Beuys's disintegration of conventional object categories. Sometimes called "Beuys-brown," Braunkreuz came to function, like fat and felt, as an autographic medium linking life and art.

Immediately, the word Braunkreuz signals Beuys's keen sensitivity to language and his penchant for word play. A cross in itself, the word is an intersection of two independent elements that creates a third whole. The combination of the words brown and cross calls to mind a number of varied, even contradictory, associations. Red Cross (Rote-Kreuz), the international relief agency for the wounded or sick, is per haps the most obvious. Braunkreuz also echoes the name of Christian Rosenkreuz, the supposed fifteenth-century mystic for whom the Rosicrucian sect was named.[37] Apart from the doctrines of the Rosicrucians, early Christian traditions associate the rose with the blood of Christ and with the secrets of the cross in general.

Beuys's substitution of "brown" for "rose" or "red," however, renders a complex transformation. The word Braunkreuz , like the appearance of fat in Beuys's work, plays ambiguously on the awareness of Nazi history and its evocations of genocide. Brown was the color adopted by the Nazis, evidenced in such terms as Braunhemd (Brownshirt), the unofficial name for Hitler's storm troopers. "Brown" became a casual adjective to describe anything Nazi —today still used in references to a braun Vergangenbeit (brown past).

The allusion to Nazism and World War II is reinforced by the militaristic associa tions the cross holds in Germany alongside its religious symbolism. The Iron Cross (Eisernes Kreuz) is a military medal for valor, first awarded by Prussia in the Napoleonic Wars and reissued by the German government during this century's two world wars. The same cross marked the vehicles of the German armed forces in the two world wars and is used in a modified form by the Bundeswebr of the Federal Republic today. Morever, the symbol of the swastika, adopted by the Nazis in 1935, ls a known in German as the Hakenkreuz (hooked cross).[38] Such associations can continue further: it is a short step to Gelbkreuz, the German term for mustard gas, used in World War I.

Braunkreuz, then, is a term loaded with powerful references not only to Christianity, the occult, and war or disaster relief, but equally to German militarism and Nazism. This complex constellation of terms —circulating around the concepts of the spirit, the wound and war —removes both the word and the medium Braunkreuz from any fixed interpretation. Beuys's homeopathic concept of art (healing like with like) allows the possibility of a purposeful link with the "brown" vocabulary of Nazism. In his public remarks Beuys never sought to clarify these multiple allusions. On the contrary, the very ambiguity of the interchange of these concepts is a primary element in Beuys's work as a whole.

One cannot look to Beuys's own statements for direct explanation of technical questions regarding Braunkreuz any more than for mention of its references. Indeed, this subject in particular has acquired the air of a house secret, echoing the clandestine nature of Rosicrucian activities. This mystery concerns, first of all, questions about the exact nature of the medium(s) used to achieve the rust-brown color. Beuys termed his Braunkreuz works Olfarbe (oil colors), as distinct from his watercolors and pencil drawings, and never specified further. Commentators have identified Beuys's brown in a variety of ways over the years. Recent laboratory analysis indicates the paint to include commercial rust proofing.[39] The great numbers of drawings made with Braunkreuz reveal a range of slightly different colors; this may result from different practices on Beuys's part (mixing the paint with more oil, for example), or on variations in the specific brand of paint available over the years, as well as varying rates of change in appearance over time.

Braunkreuz can be seen as a culmination of Beuys's interest throughout the 1950s in painting with unusual materials. It demonstrates his preference to treat his mediums as "substances" with independent values rather than as mere coloring agents.[40] While Braunkreuz technically relates to the work in oils Beuys did during the late 1950s, it more generally reflects his fascination for pigments and mediums that were to be found in nature or at the hardware store rather than a specialty art supplier. Specifically, Braunkreuz appears to be a descendant of the Beize solution with which Beuys worked throughout the 1950s, each associated with the element iron. The two share a luminosity that, in the case of Braunkreuz, works in striking counterpoint to the apparent density of the surface.

The early manifestations of this brown substance are essentially paintings on paper. The development from Beize to Braunkreuz is paralleled in the many women painted in rich brown, such as Rubber Doll, 1959, or Mystery of a Love, 1960. More boldly explicit than figures drawn during the 1950s, these women exert the powerful aspect Beuys described as that of "actresses." Beuys was rapidly defining his self-presentation, and his dual roles as teacher and performer contributed to the aptness of the shamanistic metaphor. Lapidary yet mesmerizing images such as that of the powerful Shamaness, 1963, expressed the auratic power of the person at the head of a classroom or on stage.

A good basis for an exploration of the meaning of Braunkreuz is provided by a photograph of Beuys in his studio in Düsseldorf, probably dating from 1962 or 1963. Four thin, flat bundles of folded newspapers hang on the back wall, each covered by two crossing stripes of paint. They hang isolated on the wall like medieval icons or targets. The newspapers on the studio wall are the same sort of bundles that hang on the cupboard for Scene from the Staghunt in the collection of Beuys's works now on view at the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt. Both the photo graph and the sculpture represent workplace situations. The Darmstadt Staghunt is a simple, tall, open wooden cabinet, the contents of which present the accumulation of material in the laboratory/studio: wires, old bottles, test tubes, funnels, mousetrap, metronome, twine, trash, tools, paint tubes, little toys, first-aid items, fire extinguisher, and assorted debris (a miscellany evoked in the typescript and Braunkreuz drawing of 1961, Scene from the Staghunt. Hanging in front of the cabinet are fifteen bundles of newspaper (dating from 1963), all wrapped with twine in a cross shape, painted over with brown lines about one inch thick, formally echoing the compartments of the cabinet.

As the newspapers hang along the cabinet's open front, they have the decided presence of something more than ornaments. A clue to their role can be found in a number of small objects that Beuys called "batteries," simple bundles of newspapers like those seen hanging on his wall in the photograph mentioned above. The "batteries" bear striking resemblance to contemporary works by Piero Manzoni and Marcel Broodthaers, among other artists concurrently exploring the arena of assemblage. The electrical metaphor, however, is unique to Beuys's work and relates to the artist's theory of sculpture. The friction that results from the accumulated layers of newspaper sheets produces physical warmth, while "psychological" warmth results from the accumulation of the information in those pages. To extend the metaphor, the cord that ties them (overpainted with brown and forming a literal Braunkreuz) contains that energy and grounds it. Indeed, a work entitled Ground, 1964, joins a small copper wire, which conducts electricity, to the corner of a rectangular sheet covered with Braunkreuz. The earth brown color of the paint provides a double meaning to the function of the paint as a "ground."[41]

Operating in this way, the Braunkreuz newspaper bundles and single sheets form direct counterparts to the Fond sculptures that Beuys made throughout his career. Fond is the German word for base or foundation, and as their name indicates, they form the base of Beuys's overall sculptural project. The Fond series operates on the principle of energy producers and presents, according to Beuys, "the idea of the battery as a reality and a metaphor."[42] In the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt, the visitor encounters in the same room as the Scene from the Staghunt the 1968 work entitled Fond II, two wooden tables thickly coated with copper. An actual foundation on which work can be done or things can be rested, Fond II could be charged at 20,000 volts, transformed through an inductor from a 12-volt battery. When exhibited in a charged state, as it was in two exhibitions before being installed in Darmstadt, the sculpture literally conducted energy.

Later Fond sculptures replaced the use of an actual battery with the repeated layer ing of piles of felt, iron, and copper, which produced warmth in a more figurative manner. In the case of every Fond, the function of the sculpture can be described as the accumulation of warmth to supply the power of transformation of matter, and by extension, of spirit. Beuys called the Fond pieces "static actions" because they rest in one place and yet imply activity.[43] In the same way, one can view the Braunkreuz bundles hung on the front of Staghunt as small motors for a machine, or for human creativity (to use Beuys's word, "evolution") at work in the studio or laboratory.

In Beuys's universe, the role of the warming, sculptural nature of Braunkreuz closely relates to that of felt, an analogy made clear in the many Braunkreuz drawings that evoke large fuzzy masses of that material, as well as in works such as Felt-Action, of 1963, that incorporate into the Braunkreuz drawing an actual felt fragment. Many works sharing the spirit of Braunkreuz employ an opaque gray paint more directly suggestive of felt.[44] These drawings can be beautifully minimal: a work of 1963 entitled For Felt Corners juxtaposes two small triangles, one with a wedge tipped beside it, on the inside covers of an opened sketchbook smudged by footprints. They can also be richly complex: Felt Angle and Nude of the same year, which depicts a human figure beside a sculptural form (a tall, black, angled column), employs hare's blood, milk casein, oil and a collaged piece of film celluloid. These two very different drawings share the doubled structure characteristic of much of Beuys's drawing and sculptural work, paralleling the polar structure of his theory of sculpture. These works also reflect his preference for the triangle (in three dimensions, a tetrahedron or corner), the symbol by which Beuys expressed "form" in his theory of sculpture. "Felt angles" are frequent motifs in the pictorial drawings of the early 1960s, as in Felt Angle and Nude or the eerie Dead Rat, Felt Ridge, Two Black Felt Crosses, Felt Angle, of 1963. Later in the decade, they appear in works such as Notes for an Action, 1967, as representations of the felt angles Beuys would use in performance.

The newspaper "batteries" found in the Scene from the Staghunt are paralleled in many untitled Braunkreuz drawings that are made on sheets of newspaper. These drawings partially mask the surface of the newspaper with Braunkreuz, exposing particular sections of photographs or newsprint. Beuys was extending the Cubist collage tradition, which had been explored by Germans such as Kurt Schwitters and John Heartfield, whereby the "found" photograph or text functions as a key component of the image in content as well as form. In Beuys's case the photographs or texts often refer to scientific or ecological concerns, using clippings taken from sections of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, such as "Natur und Wissenschaft " or Deutschland und die Welt." A Braunkreuz work of 1967, for example, reveals headlines linking lsd to leukemia, and reporting an artists' protest against a government-sponsored "morals clause" for films.

The reference to the "brown art" of the Third Reich implicit in Braunkreuz is explicit in a work of 1963 that paints over an advertisement to reveal the letters Pst . . , the German word meaning hush. A series of Nazi propaganda posters had been posted around German cities during the war to warn the populace —pst! —to exercise caution in the interest of national security. Some twenty years later, the word brought up the topic of silence in a new context, questioning the muteness of the modernist avant-garde (the silence for which Beuys challenged Duchamp), as well as the heavily charged issue of past and present German silences.[46]

Beuys also used Braunkreuz as overpaint in more than a dozen works centering on Greta Garbo, employing photographs and photocopies of the film star both as an actress and a retired recluse. A literal extension of the 1950s "actress" figures, the Garbo drawings convey the reality of the individual as aura, a reality that Beuys had grasped as well as Warhol. Beuys's characteristic identification with the martyr surely led him to understand Garbo's cool rejection of public life: "People take energy from me, and I want it for pictures."[47] That energy is captured in these reproductions, more real than the actress herself, and it fuels the Braunkreuz objects they compose.

The manifestation of the "brown cross" in Beuys's work during the 1960s extended beyond the literal form of his "batteries" with their crossed cords overpainted in brown. From the beginning of the decade, small painted crosses appear on a variety of objects and drawings; in a sense, these crosses are abbreviations for the polar energy dynamic more fully transmitted by the bundled "batteries." Often the objects on which the brown crosses are painted —letters, lists, drawings —date from years earlier. The basis of the drawing may be printed matter, such as a textbook chart or a magazine advertisement; several brown-crossed drawings employ technical maps and code sheets from Beuys's military service. In the case of these drawings, the information on the page's surface provides the energy of the newsprint "batteries," and the simple brown "seal," the counterpoint.

An important category of brown-crossed drawings includes the work lists that Beuys made throughout his career. These lists are the verbal equivalent of a piece such as Scene from the Staghunt in their accumulation of experience and ideas. The activity of list-making can be traced to Beuys's early studies in natural science and would continue throughout his life. Beuys began to make work lists in quantity at the time of his interest in Fluxus, when he painted over such lists with images or several brown crosses. These lists, such as List with Wolf, 1962, or Washed-Out List, Double Crossed, 1963, compose an informal inventory of the names, mediums, and dates of Beuys's own drawings. Such an annotated compilation recalls Paul Klee's oeuvre catalogue, a document with which Beuys may have been familiar. Klee's private catalogue served the purpose of record keeping, even as its meticulousness attained a form of poetry. Beuys brought the form of the record explicitly into the arena of the works that are its subject, validating the list as an object of art in itself. The lists serve as metonyms for the entirety of Beuys's enterprise in terms of their function as well as their content. All of Beuys's pieces stand as souvenirs of, or probes into, his lifelong Gesamtkunstwerk. As a list signals toward the objects, so an individual object gestures toward the whole of Beuys's career.

Beuys's work-list drawings exemplify the role of the brown cross in Beuys's formulation of Braunkreuz as a personal signature. Whereas the cross operates in terms of Beuys's central metaphor of energy production for the making of art, and the living of life, the choice of the cross as a symbol brings with it inherent spiritual references. The particular significance of the cross within the system of Beuys's theory of sculpture joins with the artist's deep and longstanding interest in its traditional iconographies. One of the key sculptures in which the small brown crosses play an important role is the small Crucifixion now in the collection of the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart. This work of 1962—63 provides the most direct link between the theme of Braunkreuz and the Crucifixion itself, made apparent in the object's title if not in its immediate appearance. The piece is composed of simple materials that share the junk-like quality evident on the shelves of the Scene from the Staghunt. Like contemporary assemblages by Robert Rauschenberg, the piece's humble elements take up the heritage of Dada found particularly in the work of Kurt Schwitters.[48]

The crude appearance of the Crucifixion belies Beuys's exacting choices for the mate rials, especially the acid-encrusted hospital blood-storage bottles that take the places of Mary Magdalene and John the Baptist. The three squares of newspaper, atop each bottle and in front of the cross, bear close reading; in this respect they, too, are descendants of the newspaper fragments used in Cubist papiers colles, whose texts often seem selected for a point. The text accompanying Mary Magdalene is an engagement notice, suggesting her holy marriage. The excerpt over John includes the word guilt,which alludes to the Baptist's call for repentance and moral purification.[49] The text of the fragment on the central beam is initially more enigmatic: an article from the newspaper's financial pages, it refers to the Zentralbank and the fluctuation of the pound. This text brings to the subject of the Crucifixion the principle of an economy and the circulation of capital therein. With this, Beuys drew a direct connection between the blood implied by the bottles and currency: that is, between the circulatory system of the human and the social bodies. This circulation model stands as the basis of Beuys's concept of the social body, later envisaged in actions and installations such as the Honey Pump at Documenta 6 in Kassel in 1977. Again and again, Beuys proclaimed that "creativity = capital," arguing that man's potential rests on spirit and imagination rather than on money and material assets.

Herein rests the connection to the Christian theme of the Crucifixion, for it is this form of capital that Beuys described as the gift of Christ to man: a mandate to act freely and to assume responsibility for one's own fate. Beuys centered spirituality and, concomitantly, creativity, within the individual. Christian symbolism under scored for him a faith in man's own creative potential, a potential that must replace money as society's concept of capital.

This concept depended heavily on the theories of Rudolf Steiner, with which Beuys had been familiar for over two decades. It was probably through the study of Steiner that Beuys became acquainted with Rosicrucianism, one of the touchstones of Steiner's teachings. Steiner felt that his mission in the twentieth century was to lift esoteric teachings into the reach of common people and to reconcile spiritual insight with the demands of modern life: "The role of Rosicrucian theosophy or occultism is to satisfy the spiritual longings of men and to enable spirit to flow into the daily round of their duties. Rosicrucian theosophy is not there for the salon or for the hermit, but for the whole of human culture."[50]

It is along this path that Beuys's vision of Christianity came to extend beyond that of the conventional church. Steiner believed that art would succeed where both religion and science had been condemned to failure by their equally narrow systematization. A similar conviction led Beuys away from an art that directly illustrated Christian tradition and motivated him to explore a way to incorporate and transform that tradition. With objects as his "vehicles," Beuys became most interested in using art as an avenue to spiritual and social revitalization. When his theory of sculpture broadened into an "expanded art concept," Beuys spoke of sculpting a society in the same terms as sculpting an object. This idea governed the last twenty years of his life, when Beuys centered his work in a variety of activist organizations and projects. When asked in an interview what he thought was his clearest example of the image of Christ, Beuys's response was "the expanded art concept."[51]

In this sense, the idea of the cross acquires meaning as a general symbol of unification. Beuys's vision of social change, like that of many other artists during the 1960s, centered on repairing a divided world and a divided self. The political bisection of Germany exemplified the wide gap between Eastern and Western philosophy, religion, economy, and government. The cross suggested for Beuys the unification of East and West necessary for a healthy society, as much as inner integration was required for a fully realized human being.

The channeling of Beuys's spiritual ideas into the monochrome visual system of Braunkreuz was as much cultural as personal. The context of the Düsseldorf art scene in the late 1950s and early 1960s provides an important backdrop for the story of Braunkreuz. This period witnessed the development of the ZERO group, which was greatly indebted to the example set by the Frenchman Yves Klein. For both Klein and the ZERO artists, the spiritual mission of art was a fundamental con cern of their work, and the solution was found in the seeming purity of a mono chrome system.

In 1957 the inaugural show at the Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf was a roomful of Klein's large canvases with rounded corners, identical painted fields of intense blue. One can only speculate on the inspiration that International Klein Blue may have provided to the invention of Braunkreuz. Yet the parallels between Klein and Beuys are striking, particularly the spiritual ambitions that motivated the work of both artists. Contemporary critics primarily remember Klein for the sensational aspects of his showmanship and his elegant critique of the avant-garde tradition in works such as his "exhibition of the void" in 1958.[52] However, Klein's work, informed by Rosicrucian study as well as by his long encounter with Zen while in Japan, rested on the vision of a new age in which the spirit overcomes materialism.[53] Klein's bold entreaty, "Come with me into the void"[54] invited the viewer into the realm of pure space, leaving behind images of the day-to-day world and the lines tracing its details and complications. The viewer looking into a blue canvas with its rolled-on paint was gazing into the infinite, uncontaminated by the painter's hand.

The repercussions of the Klein exhibition in Düsseldorf were immediately felt in the ZERO group, which had been founded in 1957 by Otto Piene, Heinz Mack, and Giinther Uecker. The ZERO artists shared the goal of an art that sought to expand human consciousness and to reach beyond the subjectivity presented by any form of expressionism or illusionism. The ZERO artists chose white as the color ideally suited to their needs, precisely because it encompassed all colors and thereby generalized the artistic statement. All-white canvases announced an attempt to overcome materiality and to arrive at the weightlessness signifying the highest of spiritual states.[55] Springing from these Utopian goals came the desire of the ZERO artists to enter into the social context, literally to transform daily life beyond the picture plane. In July 1961, in conjunction with an exhibition at the Galerie Schmela, the first zero festival took place in Düsseldorf. It was organized as a "Festival of Light" complete with mylar foil and balloons, fireworks, and a parade. With an earnestness that recalls the Dada festivities of Hugo Ball, these artists set out to clothe contemporary reality in an invented one. Even the pavement of the street outside the Galerie Schmela was painted white for the occasion.[56]

Against this backdrop of a white Düsseldorf, Braunkreuz takes on a pointed quality. Beuys's spiritual concerns as an artist were by no means unique, and yet there is a dramatic difference between Beuys's approach and that of Klein or the zero group. Klein set out to visualize the absolute that denoted the coming age, but Beuys seemed to face the opposite direction. The texture and color of Braunkreuz appear to present all the weight, materiality, and ordinariness that his peers wished to escape from or replace. Rather than imagining man's disappearance into the sky, man's "leap into the void," Braunkreuz seems to confirm his attachment to the ground. This recalls drawings from the 1950s in which Beuys depicted himself as contained in stone or merged with the earth. One thinks also of Beuys's Double Fond, 1954-74, a sculpture composed of two iron blocks (one with copper clad ding), a steel rod, and a steel plate. Beuys's accompanying inscription states: "These iron blocks are so heavy that I cannot easily escape from this Hell."[57] Adapt ing a traditional Romantic theme, Beuys addressed the dilemma of the artist whose lofty aspirations are confounded by human physical limitations.[58]

Beuys's motives in selecting Braunkreuz as his medium for a spiritual project involve a mechanism that is also evident in the sculptural materials he used. Paradoxically, Beuys chose a brown color evoking dirt, dried blood, rust, or excrement to stand for a nonmaterial realm. The meaning, therefore, must be derived not through illustration or conventional symbolism, but rather, by a dynamic of contrast. Beuys described this strategy concretely in an interview with Jorg Schellmann and Bernd Kliiser in 1970, discussing why he worked with felt:

The phenomenon of complementary colours is well known if for instance, I see a red light and close my eyes, there's an after-image (ocular spectrum ) and that's green. Or, the other way round, if I look at a green light, then the after-image is red....

So it's a matter of evoking a lucid world, a clear, a lucid, perhaps even a transcendental, a spiritual world through something which looks quite different, through an anti-image. Because you can't create an after-image or an anti-image by doing some thing which already exists, but only by doing something which is there as an anti-image, always in an anti-image process.

So it isn't right to say I'm interested in grey. That's not right. And I'm not interested in dirt either. I'm interested in a process which leads us away beyond those things.[59]

The same attitude is reflected in Beuys's comment about why the objects used in the performance Coyote: I Like America and America Likes Me were overpainted with brown: "Through the blockage the light colors or spectral colors will be directly driven forth as contrasts."[60] This explanation depends on the nineteenth-century color theories of Goethe, whose writings meant a great deal to Beuys. Here he echoed Goethe's observation that "if we look at a dazzling, altogether colourless object, it makes a strong lasting impression, and its after-vision is accompanied by an appearance of color."[61] This counterpoint is suggested in several Braunkreuz works Beuys made on the pages of technical color charts, the squares of pretty color revealed beneath the plastic substance of the brown paint.

Beuys's use of brown paint, like fat and felt, led to accusations that Beuys made ugly art. While Beuys staunchly denied that he found felt unappealing (responding, for example, that if felt were so ugly, why did men wear felt hats all the time?[62]), the strategy was clear. Beuys's attitude toward material signified a rejection of conventional notions of culture, in a grand modernist tradition of "anti-art." He found in Braunkreuz a paint that looked like the paint on people's floors —an art to step on. Its color evoked not only the ground but also waste or decayed material. The very manner in which Braunkreuz was applied —it was by nature a form of overpainting —constituted a gesture of opposition, of wiping out or covering up.

Beuys's approach adapted a realm of imagery that involved the supposedly ugly or unvalued, an avant-garde tactic since the early days of Romanticism and throughout the twentieth century. Both the Expressionists and the Dadaists, for example, incorporated into their aesthetic a profound distrust of the material and professional conventions of Western art. Kandinsky had celebrated the primitives for "renouncing ... all considerations of external form,"[63] a claim that reflected his fantasy rather than actuality. When the Dada artists chose that nonsense word as their collective name, its members pretended to similar ingenuousness.

In the work of artists ranging from Duchamp to Malevich, Dubuffet to Rauschenberg, the path of twentieth-century art repeatedly dislodges the accepted trappings of high culture. Yet the anti-art posture, in the case of Beuys as much as his predecessors, reinvigorated an evolving tradition. Often, the concept of anti-art marked a refusal to accept the restricted territory granted to art in the modernist era. Among the Fluxus artists, especially, the attraction to detritus and ephemeral elements expressed their opposition to commodification on the art market or memorialization in museum galleries. Beuys's involvement with Fluxus during the early 1960s reinforced his idea of art as something that could look less important than it was.

Braunkreuz never became exclusively associated with Beuys in the same way as did fat and felt, or as International Klein Blue became the trademark of Yves Klein. Nonetheless, the Beuys signature was implicit in Braunkreuz and, for this reason, Braunkreuz played a key role in the development of Beuys's production of multiples during the last two decades of his life. Braunkreuz provided the path from the unique work to the large editions of multiples that could function efficiently as object-autographs, Beuys "antennae" that could radiate his message to a large public.[64]

Beuys's first multiple, Two Frauleins with Shining Bread, a complex play on the concept of transubstantiation, has as its center a bar of chocolate overpainted with Braunkreuz.[65] His next multiple, the first that Beuys produced with the gallery owner and publisher Rene Block, was entitled . . . with Braunkreuz. It extended the strategy of creating new works of art by putting small brown crosses on pre existing images. Each of the twenty-six numbers in the edition included one brown- crossed drawing, typescripts of two stage plays of 1961, and a half-cross made of felt. Painted in large block letters on the cross was the word BEUYS, flanked by two small brown crosses that echo those framing the drawing. United in a handmade linen box, these items supply a composite of Beuys's work: texts, image, and sculpture, as well as the concept of the name. Following the model of the many "anthologies" published by Fluxus, and ultimately the Box-in-a-Valise made by Marcel Duchamp in 1941 to house miniature reproductions of his own works, . . . with Braunkreuz provided a small Beuys survival kit. Completing that metaphor, in one box of the edition a gas-mask bag was substituted for the drawing.

Beuys's next multiples provide the transition from the individually painted brown cross to the array of stamps that cover his work from 1967 on, marking sculptures, photographs, drawings, posters, postcards, and drawings.[66] Created with an ordinary rubber stamp pressed to an ink pad, the stamp was at once a method of personalization and a banal part of everyday life, omnipresent in Germany more than in America. The rubber stamp was emphasized in Fluxus work during the 1960s, although it dates back at least to the drawings of Kurt Schwitters. For Beuys, the debut of the stamp occurred in the multiple following . . . with Braunkreuz, the catalogue that accompanied the one-man exhibition at the Stadtisches Museum in Mon chengladbach in 1967. The book's felt cover is in the form of a modified half-cross. Stamped in brown across the felt is the word BEUYS with a cross stamped just beneath the U.

The same stamp marks Beuys's felt suit, a multiple of 1970. The suit had a precedent in an outfit Beuys displayed at the "Demonstration for Capitalist Realism" in Düsseldorf in 1963: a man's set of clothing with small, painted crosses pinned to it.[67] The evolution occurring between those two suits reveals a refinement of Beuys's language but no change in his intentions. The Christian and historical allusions of the earlier costume surface in the stamped felt-suit multiple. Beuys discussed the felt suit in terms of the warmth it provides, that is, "a completely different kind of warmth, namely spiritual or evolutionary warmth."[68]

The "Beuys" stamp soon evolved into others, and the stamp became a ubiquitous part of Beuys's work. The Hauptstrom stamp, for example, became part of any works Beuys considered to embody the central currents of his thought; other stamps named Beuys's organizations (such as the German Student Party, the Organization for Direct Democracy, and the Free International University) or favored slogans ("Beuys: ich kenne kein Weekend" ["I know no weekend"]). The appearance of these stamps on Beuys's works depends directly on the precedent set by the brown crosses used to mark drawings and objects throughout the early and mid-1960s, but the mood was now different. The proliferation of the stamps signals what might be considered the next phase in Beuys's career, after the period dominated by his teach ing at the academy and his early actions. During the end of the 1960s Beuys's methods expanded to use his personal celebrity as a vehicle for a group effort to achieve world change. The individual identity "Beuys," as it was integrated —indeed stamped —into every work, at the same time opened out to include the idea that everyone is an artist.

Bender of space: the Human (h)

Bender of time: the Human (h)

(Joseph Beuys, from and in us . . . under us . . . landunder, 1965)[69]

One of the many paradoxes of Beuys's art is that the works for which he is perhaps most remembered —the actions of the mid-1960s and early 1970s —are those that are least available to memory. A limited number of people actually witnessed them, and remarkably few of them were recorded on film or video. The actions survive most prominently in often-reproduced photographs and in the objects used during performance that are preserved as autonomous works. They also survive through a number of drawings that relate to the individual actions, now scattered among various collections. These drawings, usually combining text and image, are collectively known as Partituren, the German word for musical scores. This general usage derives from Beuys's own frequent, although by no means exclusive, tendency to refer to an action-related drawing as a Partitur.

Beuys's scores comprise an extremely diverse body of drawings, sometimes serving as working notes for an action, sometimes as documentary records. In general, the drawings name or illustrate objects used during the event, list key phrases that Beuys recited aloud, or elaborate the conceptual foundation of the action. Never are they complete accountings of all that would take place. By definition, as drawings, the scores cannot convey the mesmerizing quality of Beuys's gestures, the sensory complexity of the experience, the immediacy of the political moment in which they took place, and the mood of the audience in attendance. But precisely because the scores exist explicitly as fragments, as incomplete elements, they signal the absence of all the rest while they permit a unique perspective on the actions themselves. As such, the scores share the spirit of relics surrounding the action-related objects now clustered in Beuys's vitrines at the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt and other museums and private collections.

Beuys's actions remain the most spectacular enactment of the Gesamtkunstwerk aesthetic that pervades his work.[70] His commitment to the notion of creativity as aresource that supersedes departmentalization as well his own strong sense of music and theater made the actions primary touchstones for the strikingly international and interdisciplinary avant-garde of the 1960s. In the United States, the medium of happenings brought artists out of their studios to stage seemingly improvisational (although often tightly planned) events in lofts, galleries, backyards, and on the street.[71] In Austria, the Actionist movement developed a much more aggressive and sensational theater based on the principle of catharsis.[72] Germany was the center of Fluxus, a worldwide movement in which artists, poets, and musicians used performance to return to art its sense of play. Live performance was an ideal medium for a group that stressed the ephemeral nature of art in a universe of "flux."

The myriad achievements and interrelationships of the artists involved in Fluxus, happenings, and Viennese Actionism have only recently begun to be charted. Their documentation has been hindered by the very qualities that attracted artists to performance practice in the mid-1960s: its resistance to the compartmentalization of art history and institutions. The blend of text, dance, sound, and visual image attained an importance not witnessed since the activities of the Futurists and Dadaists in the 1910s. Like those predecessors, most of these artists shared strong political commitments, even if often veiled by the comic or mystical aspect of their activities. The German word Aktion, employed by the Viennese as well as by Beuys, has the connotation of a political or military maneuver. The politicization of culture during the 1960s resounds in the Fluxus manifesto by George Maciunas calling to: "FUSE the cadres of cultural, social & political revolutionaries into united front & action."[73] The involvement of the artist with an audience metaphorically signals or implies a desire for an art that has more integral connection with life than that of the formalist strain of modern painting or sculpture.[74] While most of Beuys's actions did not explicitly present topical content, the artist's self-transformation in performance beckoned toward individual and societal transformation beyond that arena. Recalling The Chief (1964), in which he lay rolled in felt for nine hours at the Galerie Rene Block in Berlin, Beuys explained that "Such an action, and indeed every action, changes me radically. In a way it's a death, a real action and not an interpretation.Theme: how does one become a revolutionary? That's the problem."[75]