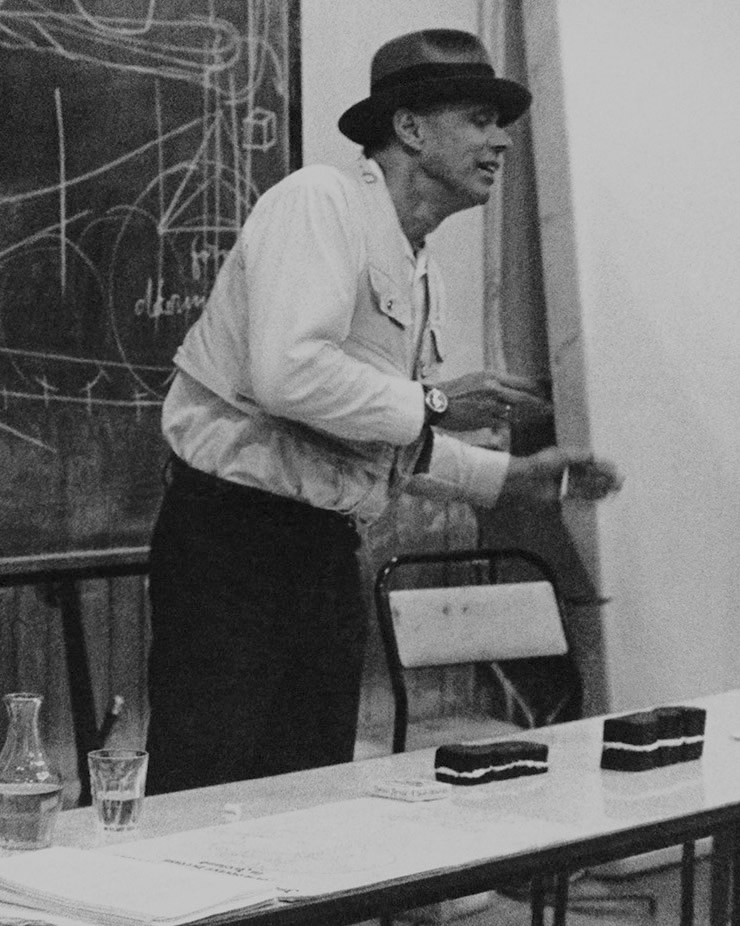

“I put me on this train!” An interview with Joseph Beuys: Art Papier

Joseph Beuys, Crawford Art Gallery, Cork, 1974

ART PAPIER: Joseph Beuys, do you have a mission?

JOSEPH BEUYS: Yes, perhaps I have a mission . . . to change the social order. To change the money system mostly, that's the most important thing, the money system. Money and the state are the only oppressive powers in the present time. Money and the state and the [interaction] between these blocks. There is no other power and as long as people go to vote and go to the polling booths and say yes, yes, yes, to this system, as long this system will survive. And so we go radically another way and push against this Radically.

PAPIER: I heard you say in a recent television interview that you don’t look towards America for this kind of radical social transformation that you feel that Germany or Central Europe will probably be the place where it can happen, because in Germany change can happen more quickly.

BEUYS: This is what I think. It is only an estimation, you see, I was not judging. I said probably. Now this the sixth time I've been in the United States, with dialogues, with actions, now with a kind of exposition. I have in the meantime had some experience with the American scene and I admire and I like America. Like on the poster that was to be seen: "I like America and America likes me." That's true, but I feel that in Central Europe, at the moment there is much more tension and much more power in the discussion about the future of society. So I feel Europe will maybe, perhaps or probably, be the spot where the new ideas come up, in the next one, two, three years; that's what I think.

PAPIER: And this process will come through a democratic change, will involve direct democracy?

BEUYS: Yes sure, that is what I think. I am against the kind of revolution done from one day to the other, with a kind of putsch character, you know. So I'm working in a more revolutionary way, going the organic way, finding as much as possible people supporting such a movement, so. I try with a movement on the grass roots . . . against the ruling systems not only in Central Europe but in every part of the continent. . . . A democratic system is already working, with more . . . and more, minorities working on their grass-roots problems, pushing against the system. I see already running within the Free International University or in similarly shaped organizations, the impact and the results of a kind of direct democracy.

PAPIER: None of what I've seen or read [about your work] speaks directly to the political realities of your life. Yesterday, I heard you talk about the evils of economic profit in philosophical terms. Let's talk about profit in terms of your show at the Guggenheim Museum. What does this exhibition mean politically and economically for you?

BEUYS: Politically, it means perhaps a lot because there is a good impact in West Germany. If a person like me does succeed in a foreign country, and especially in New York, in the United States, and at the Guggenheim, it brings a lot of impact to people who are in a way enemies of my intentions in the cultural scene, in democratic discussions, in economic proposals.

PAPIER: Economically, in the long run, this can mean a lot for your work?

BEUYS: It could mean a lot for my work on the side of business and on the whole side of the economic value of objects. But because, and since, I am no longer working in the object, in making things, and I am working more promoting political ideas within West Germany and other countries, like the Netherlands, England, and Italy, I will surely not be a producer of objects which [make] money on the art market. But, on the other hand, I have to care for money because the whole organization of the Free International University, for instance, needs money. Every person who is involved with the Free International University doesn't take an income from the organization. Everybody involved has another profession from where he takes his income. So we try to establish a kind of internal bank system where everybody gives as much as possible to the pool.

PAPIER: So you give a lot of your money to the Free International University, to this pool?

BEUYS: Yes, sure.

PAPIER: Does this increase your power with the Free International University?

BEUYS: The Free International University is a political movement. And during election processes like the election of the European parliaments and now, with the coming federal election in West Germany, we surely are in very bad condition if we have to raise money. For instance, information in the streets, actions, going on trips with the material, speaking in different towns and all such activities, cost a lot of money. Therefore, we need a kind of pooling system. And I try to do as much as I can to fill in because I sometimes have a better income than other people. Sometimes, it's a big quantity I can give, sometimes it's less, you know. This relates to the production of art articles—giving in the art market—so I cannot completely stop this production of sculptures, art objects, which result in this capitalistic system for money. One must see that I try to overcome the political system and try to develop a kind of enterprise, with other descriptions than the capitalistic enterprise and understood as a so-called free market, in business and all the other things. [For] surely every work has to be organized in a kind of enterprise or structure.

PAPIER: But doesn't that increase your importance in the Free International University, giving that money?

BEUYS: No, no, nobody has special importance in the Free International University. It is not a hierarchical organization.

PAPIER: You say in your manifesto for the Free International University that the traditional student/teacher relationship must be broken down, that it cannot be one-way, it has to be a dialogue, not a monologue.

BEUYS: That's exactly right.

PAPIER: Yet you remain at the center of the German Free International University. How important are you to the Free International University?

BEUYS: How important? I founded the Free International University. I shaped the idea. After I had done the Organization of Direct Democracy then later on I found it necessary to go on with a research enterprise and with a political movement related to every field of the society. Not only towards the ecological problems in democracy, but also to the freedom problem in creativity and then later in economics also, to change the understanding of money, to change the whole understanding of capital. Therefore, I founded the Free International University, but even though I founded the Free International University, I have no privilege in this organization. Everybody has a completely equal right, equal say, and there is no privilege. Everybody helps everybody as much as he can.

PAPIER: What I don't understand is: the Free International University is a democracy, you tell me everyone is important there, everyone has an equal say: then why so much attention on Joseph Beuys?

BEUYS: Yes, perhaps because I founded the whole idea and a lot of people feel it as a very radical intention to go and run this way. In a way it is a kind of innovation in the whole political discussion and also in the understanding of what art should or could do in the world as political power, art as a political power. Therefore, you see, it is in a way the new character of the things which makes people interested. And, on the other hand, it is surely the established information structure which tries to go the old way, which tries to work with the star…

PAPIER: But aren't you the star?

BEUYS: Yes, I am the star in a way. It's true. I admit this, but I try to use this position.

PAPIER: Do you encourage stardom?

BEUYS: No. Encourage it? I encourage the ability and the dignity, and the necessity to look at everybody's creativity.

PAPIER: You say you don't encourage stardom, but I see you publicly signing catalogs and posters. Your multiples cost a lot of money. People buy ownership of Joseph Beuys objects. The concepts seem very unimportant to these people.

BEUYS: But, you see, I don't judge about how people work, watching what they take out of catalogs, political manifestoes or things, I don't judge.

PAPIER: Okay, let's look at the multiples that are for sale in the museum. A $50 felt eraser with your signature—what intellectual, political value does that have?

BEUYS: It is a kind of vehicle, you know. It is a kind of making, spreading out ideas, that is what I think. It spreads out the idea. You must care for information and I personally try to make information available not only in a written way, in a logical description of the steps we should take in the future towards a liberal, equal and social society. I try also to work with images, with fantasy, with jokes, with humor. It accelerates the discussion of the problem of a new society. A new society is really something other than what some so-called socialists think the class struggle theory of Marx means. I think in a real other way of the future of society. You know, that is a problem. So I work coming from the idea of art as the most important means to transform the society.

PAPIER: You see yourself as being important in discussing these issues in the coming years. Do you think it is important for you to live a lifestyle that is consistent with your philosophical beliefs?

BEUYS: My lifestyle should be parallel to what I say, yes. I inform about possibilities, philosophies and ideas for life and future, and I cannot live radically another way, that would not be a very good example. But I think more and more people feel that I try at least, I try to do what should be in a way a kind of ideal. I can only say in this modest way I try to give what I can give. Yes, I try everyday new things. I try to be up and think over again what would be the next step and how I should behave. And so there is a moral intention also. It's implied in the whole thing. The morality of this thing is very important.

PAPIER: And you feel that your actions are consistent with your beliefs?

BEUYS: Yes, my actions are consistent during the last twenty-five years. But in every year I can see a kind of progress in details, I can see that there are a lot of details ameliorated in considering the problems for everyone's freedom in the cultural scene, also in education, schools, universities, information level, radio, television, newspapers. I see a progress in considering and research in the law, human rights question as a democratic power sphere, and during the last five to six years, the Free International University. And with the help of very able friends and philosophers in Germany, [we can] develop the kind of economical model which would content the majority in that moment where the majority of the people can understand that this is a concrete and very solid proposal for a solution of the social question all over the world.

PAPIER: In your work for social transformation, do you want to avoid the profit system or be part of it?

BEUYS: No, I try to avoid the profit system . . . I am against the profit. But as long as I live in the capitalistic system I would be stupid to relinquish my money because I have to deal with the struggle against the system, and therefore I need the money to struggle against the profit system. But when the whole system is delivered by the majority of the people, and new laws are existing on the economical level avoiding every money thing, then everything is through. But as long as things are not through, I have to care for money to work against the system.

PAPIER: In that process, you come and have a show at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. They are also profiting from your show. For them politically it means a lot to have Joseph Beuys, the radical artist from West Germany come and show, for them it increases the image of the museum, in economic and political terms. Do you agree with that?

BEUYS: Sure, I think.

PAPIER: So at the same time you are feeding them.

BEUYS: No. Yes, I am feeding them, but feeding them also with new ideas. If you read the catalog then you see that the feeding process is also against the established position of this institution. And because the whole world [consists] only of institutions one has no other thing to do than to go in with new ideas in the institution. Every family is already a kind of institution, yes, every person in itself is an institution. One can only work with institutions and bring other ideas [into] this institutional structure.

PAPIER: You say your ideas are new, if not radical and revolutionary, yet you get incredible support from the West German government. Why are they supporting you? If they are somewhat to the right, if not reactionary, why do they support you, a leftist artist, an artist who offers and suggests a whole new direction for society?

BEUYS: I don't know, perhaps they have the idea that it is necessary. That there is another reason to pay for the thing ... No, they are not open-minded, but they have the fear of losing their face. Their system tries always to work with the image of their own particular freedom, pseudo-freedom. Everything is untrue, but they try to misuse the artists to make propaganda for what they call "we are free." So they also use the artist to make propaganda for their own system.

PAPIER: So they are using you?

BEUYS: Sure, they try to use me, but it is impossible to misuse me, because I go radically another way. I take their money out of their pools, and that's very interesting to do—and they should pay, the government should pay everything of the Free International University and then the thing would run. Very, very quickly and very easily you would reach another level of society.

PAPIER: So you will be the one to pull the money out and they don't really understand that you are going to put this money to a radical use.

BEUYS: At the moment they don't perhaps . . . In the meantime some people know already the system of which I work, I try to pull the money out of the system. But there are also examples of people who have more than other people—in a way privileged personalities—who try to change the system. There is not only the so-called underprivileged people interested in changing, but also people who have more money, rich people, are inclined to support such a movement. There is also a kind of what one calls in Germany Maecenas, who give a bit . . . sometimes more.

PAPIER: So there are people on the right who sympathize?

BEUYS: So what do you call right? Right and left doesn't exist, that's an illusion. Right and left doesn't exist anymore.

PAPIER: There are very wealthy people in Germany who support you?

BEUYS: They support the revolution.

PAPIER: They support the revolution. Doesn't that give them privileges? Now let me ask you this: is that a democracy, for them to use their money to influence the system? It means they have more power.

BEUYS: You say generally that all people that have more money are inclined to be against revolution. That's not true. Surely, the people who have more money are a minority, yes . . . [but] it is not the guilt of these single persons that they have more money, it is the guilt of everybody that they gain so much money. Therefore, if anyone is to be charged with guilt, one has only to look to themselves, to ourselves. Everybody is guilty in the system because everybody every morning has to ask: "How much do I work against the system? What did I organize against the system?" So everybody is guilty for the system and not [only] the so-called capitalist people who have more money than other people . . . If the people are clear that this use of capital in the society is a false one, why don't they rise from the grass roots and lay down their work? In the workers' factories, in Ford, Chrysler, in Germany in Mercedes-Benz, in the iron factory, in big business? No, as long as workers are supporting the capitalistic system, as long the capitalists will be there. And people with privilege and more money in their pockets—that's the system.

PAPIER: What role will you play in future politics?

BEUYS: In future politics I will play the role of a person who can show how money, capital, the idea of capital could change, away from an understanding of capital as a changing fate, where everybody's dignity is exchanged as a commodity, the so-called salary dependency. [To show] that money should shift to a democratic regulator of everybody's work, creativity and dignity. So I would call this kind of understanding of money, the dignity money, the ability money of the people. Therefore, the only need for democracy is to look for this and to see that [the] only means to change democracy is to change the understanding of money and the state. . . .

I can only work as an informer. I can only appear in different places, in universities, in the streets, during democratic processes, in election processes and speak about what I think about possibilities: how the future should be, should look, and how freedom should be organized. Equality in the democratic legal structure should be built up and the understanding of capital in economics should be radically changed. So I can only make information in a kind of program where people can see there is already a solution proposed. There are already existing morals.

PAPIER: That is your role, only as a teacher?

BEUYS: As a teacher, as an informer and an organizer who faces the people, who wishes, who could be perhaps, some influence in the parliament. That's my role now, to inform the people about possibilities, to organize the resistance against the system, and to organize elections. So I could run for a position in the parliament. I could, I did it already.

PAPIER: Are you interested in doing that in the future?

BEUYS: I am perhaps running for a federal election. I'm not really clear if this will then be the right decision, but I think it could run this way. Once sitting in the parliament, you have a lot of influence on the media; the media is then no longer able to push new ideas aside.

PAPIER: You seem to have a lot of influence on the media right now.

BEUYS: Yes, but you see every important political dimension of the thing gets cut out. They include only the traditional understanding of art and art activities in the given cultural scene, in the very boring, the "nicht existent" outside of the world and very far divided from the needs of the majority of the people. So I try to cut it out, and I try to bring it in—that's the only thing.

PAPIER: But why were you on the cover of a newsweekly, like Der Spiegel?

BEUYS: When I was five years old I was not on the cover, when I was thirty years old I was not on the cover, when I came out of the last World War I was not on the cover, when I made my first exposition I was, I think, thirty-four years old, I was not on the cover—even ten years later I was not on the cover—but with the propagation of a new understanding of art creativity and new understanding of art [working] towards social change, then I appeared slowly on the cover. I pushed it, I worked for this, I struggled for this, I put me on this train! Working in the streets, working in the open. So I made something from which the people felt, "Oh, let's look, there is an idea, perhaps very interesting to hear about" and so it came to the surface. I appeal only to the people to do similar things.

So at least, let me say I try, I try to do things as well as I can. And I can only encourage other people to do the same thing or similar things. This perhaps is a real other methodology because the whole movement can't be a conformity in itself. It has to be in a very manifold way, because what the system fears is manifoldness of people's intentions and inventions against the system. If you work with an ideology, for instance, a Marxist ideology, you will never succeed against the system. They take it over to their own things, yes, every system in the capitalistic system is already working inside with a kind of capitalistic sort. So the only methodology is the color, the manifoldness in the unity. The unity means the liberation of the people from the dependency of money and state in a given structure. So that's what I think.