The Drawings of Joseph Beuys: Anne Seymour

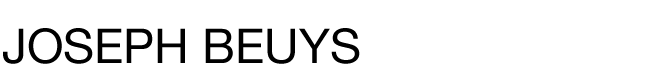

Joseph Beuys, Kleve, 1950.

The look of a drawing by Joseph Beuys is unmistakable, despite the astonishing variety of materials, methods and sizes he crowds into that category. This can encompass oil paint, gold paint, watercolour, plant juices, chemicals, blood, chocolate, 'Braunkreuz' — an invented name for a certain type of common brown floor paint, collage of virtually anything flat from pressed flowers to felt and toe-nails, and that inimitable sensitive pencil line on every kind of paper, torn, cut or pristine, on cardboard, notebook and diary pages, sketch-books, kitchen lining paper, tracing paper. He also makes drawings on wrapping paper, newspaper—whatever is to hand. One would know that line anywhere, tenaciously encircling imaginary space and ideas, metaphorical, political, social, scientific; translating, formulating previously inexpressible messages from spheres beyond the visible, inscribing them in spidery German, or sometimes German gothic script, often in English, sometimes in Dutch, even in Latin, with that characteristic handwriting suggestive of the scratchings of some Shaman's magic stick.

Drawings may represent isolated thoughts or they can be for specific sculptures and installations (there is never a literal transfer of ideas, always some metamorphosis in between), most concern recurrent preoccupations which may or may not become visible in sculpture, although—Franz Joseph van der Grinten has pointed out—Beuys perceives the sculptural problem in some way in all his projects.[1] A single drawing, like the magnificent twelve part The Cable, 1970 or the six part In the Morning the Shepherd Saw 1959 can extend over several sheets. Often drawings are composed of between two and half a dozen sheets mounted together in a particular way. And in a number of cases in his life, Beuys has brought together huge blocks of individual drawings which nevertheless relate to one another and are kept together in perpetuity—such as the 266 drawings of The Secret Block for a Secret Person in Ireland (exhibited in Ireland and England in 1974), or the additional chapters extending James Joyce's Ulysses, or the Leonardo Codex drawings.

Beuys's drawings may look like drawings or watercolours in the conventional sense, sensitive figure drawings, landscapes, flowers—but can also look rather different. They may take the form of lists, for example of fascinating groups of things botanical, medicinal, even of the materials we throw away (SEDIMENT, 1919) or of the names of his ancestors (CLAN, 1964). Another use of this listing approach has been in Beuys's scores for plays or actions such as One Second Play 1961 and Play 17, 1963. Drawings can also look like scraps of geometry or algebra, they may be dotted with calculations, diagrams, names or brief phrases. Before a lecture Beuys sometimes makes a resume of his ideas in just such terms on paper, which are then re-examined during the lecture itself as a huge blackboard drawing. The attractiveness of a drawing's appearance is no indication of the relative importance of its contents and is certainly not Beuys's primary intention.

It seems almost incredible that any one person should be able to feel so much, think so widely, see in such detail and from so many connecting points of view. The sensation of a multitude of ideas pouring from a teeming brain is overwhelming. But it is nevertheless a very organised brain, and although we cannot hope to cover the full range of Beuys's activity in 150 drawings out of any thousands, the aim of this exhibition is to demonstrate some of the basic themes and ideas which appear in them and through which Beuys makes known his view of the world: recurrent images such as the deer, the hare, the bee and the swan, the role of the Shaman, revolution, social order, the future, theories about sculpture and the wider understanding of art.

If there is a feeling about the drawings of looking over someone's shoulder, of seeing what they see as they peer into a microscope, of watching them make calculations, a suggestion that each drawing is private as a thought is private, there is also a public aspect which is equally important. It is not just that the ideas which concern Beuys are vast or universally relevant, but that they are being explored for the precise purpose of provoking society through art towards a wider understanding of itself and its problems. To this end Beuys's whole life has also become a part of his work and it is in the drawings that the ideas, which later take three dimensional form in the sculpture and actions and lectures, often find their first expression.

`With me', Beuys told Heiner Bastian and Jeannot Simmen, with typical driving understatement, 'it's that certain questions—about art, about science—interest me, and I feel I can go farthest toward answering them by trying to develop a language on paper, a language to stimulate more searching discussion—more than just what our present civilisation represents in terms of scientific method, artistic method or thought in general. I try to go beyond these things—I ask questions, I put forms of language on paper, I also put forms of sensibility, intention and idea on paper, all in order to stimulate thought And I not only want to stimulate people, I want to provoke them. Even if this provocative character, especially in the drawings, isn't particularly blatant—it goes all the deeper. My drawings make a kind of reservoir that I can get important impulses from. In other words they're a kind of basic source material that I can draw from again and again.’[2]

Beuys's early watercolours hung on his school staircase, but his parents were not at all keen on his becoming professionally involved with art. They paid for him to go to high-school, encouraged his interest in natural science and seem to have hoped that he would study medicine. Failing that, a future in the local margarine and butter factory seemed a good prospect (something that later amused him very much when making use of the substance as a sculptural material); an artistic career, which clearly began to attract him increasingly in his teens, was regarded as a disaster.

How they could have imagined that this remarkable boy—interested in anything and everything, with such phenomenal intellectual equipment and independence, who learned the principles of casting from the local blacksmith at the age of four, was acting out the history of Ghengis Khan in his games at the age of eight, was collecting and cataloguing biological specimens at the age of ten, who played the piano and the cello, appreciated the sculpture of Lehmbruck and frequently visited the studio of local sculptor Achilles Moortgat, constructed a scientific laboratory at home and joined a circus where he demonstrated talent as an escapologist—could ever have fitted into a job at a margarine factory, remains a mystery.

Born in 1921, Joseph Beuys was an only child. His father had a fodder store and the strictly Roman Catholic family lived on the German/Dutch border, first in Cleves and then in nearby Rindern. Apparently Beuys always felt himself a loner, an outsider, and hard times and busy parents left him much to his own devices. However at no time in his life does he seem to have had any trouble acquiring knowledge of all kinds, often outside the humanistic school curriculum, and including large amounts of natural history, country lore and customs, local history and mythology. He seems to have learned early on about the landscape in which he lived—a landscape like no other in Germany. Even today, on a winter visit, one gets a striking sensation of time past from this vast fertile plain of the Lower Rhine valley, bounded by the Reichswald on one side and the endless plain of Eurasia on the other, dotted with enormous isolated farmhouses and the occasional clustered town rising through the mist, where hares criss-cross the frozen grass and swans populate the tributaries and dykes. Then it must have seemed even more deeply and continuously part of history, stretching back through the wars fought across it which have determined European history, leaving behind a mixed German and Dutch population, (Dutch Couple, 1951) which takes little notice of the border and in Beuys's time still enacted many ancient customs and cults, in particular those to do with swans—from childhood a life long preoccupation and later a central image in his work.

The experiences of this period, (‘a sense of place' seems a lukewarm term for such powerful personal identification as Beuys's with a place as a source of meaning) were to become of crucial importance. In the wider view perhaps the impulse began in the 18th and 19th centuries; recently it has gathered new momentum and several artists younger than Beuys have been similarly affected in the past 15 or 20 years, in some cases as a direct result of Beuys's example.

A relatively idyllic childhood was terminated by the war. Living in the country and on the border Beuys had been fairly little affected by the Nazi rise to power. He went on the Stemmarsch to Nuremberg with the other local boys and attended the odd book burning, but that he seems to have been most interested in salvaging some of the books for himself (in his role as outsider he wanted to read everything forbidden by the regime) rather sums up his view of it all at the time.

However, the period of the war turns out to have been as important as any in Beuys's life and was clearly a vital period of emotional and intellectual growth. There were perhaps four main aspects of relevance for later developments. First of all, until 1943 Beuys kept up his scientific interests, studying in local universities wherever his duties, first as a radio operator and then as a fighter pilot, took him. However, that year, in the middle of a lecture on amoebas, the dead end he might be heading for in specialised science suddenly seems to have struck him with horrifying clarity. Secondly, his interest in art, which he had maintained through drawings and watercolours remarkably similar in appearance to later examples, seemed to offer an alternative. Third, it seems likely the war itself was playing a part in stimulating Beuys to feel a need to do something that would radically change the appalling situation society had got itself into. And fourthly, during the same year, 1943, he was shot down (he was seriously injured on five occasions in all, resulting in an award for bravery) in the Crimea, where he was rescued by local Tartar tribesmen, who wrapped him in fat and felt to help his body regenerate warmth. This now famous event, in which Beuys brushed with death and resurrection and discovered the healing properties of these warm and insulating materials, not only confirmed and extended his interest in the relevance of the customs of such so-called 'primitive' cultures, but later led him to use fat and felt as sculptural materials. (Which is of course additionally important in that it demonstrates Beuys's continual seeking from childhood on for patterns of connection and significance in the events of his life.)

Beuys has described his decision to opt for art as opposed to science on many occasions. 'In the beginning', he said in 1979, 'I was interested mainly in developing a methodology for thinking about art and science. My drawings were one motive in this respect. At an age where most people have their set careers, I made a decision that was almost theoretical—science didn't look to me as if it would have given me the chance to create something stimulating, something that would lead to change. I had this historical aim in sight, the fact that something had to be radically transformed, and I knew that art would be the right experimental field to do it in.[3] Elsewhere in the interview he expanded the idea. 'I had a feeling that I had to choose a different method, I had to produce something in my laboratory that would provoke people, get a stronger reaction out of them, something that would make them think about what it means to be human— creatures of nature, social creatures, free agents.’[4]

Although he finally chose art as his platform, Beuys remains by nature a scientist, not least because he has that kind of universally enquiring mind which he admires in others—such as Leonardo, Galileo, Darwin and Faraday. He makes it his business to know what materials are made of, how substances are formed, how they relate to one another, what their properties are. And he extends his attitude to materials to cover mental concepts, patterns of thought and states of consciousness. His interest is in discovering human parallels in the physical construction and life processes of the world we live in, and in the lessons we learn from our surroundings, to which end he also makes use of a wide range of other branches of learning, from anthropology to geology, from political science to economics. In short, his concern is to identify and explore the forces which give meaning and direction to life, even though these are not all necessarily analysable by scientific means. His action Manresa, of 1966, (named after the village in the Pyrenees where the soldier Ignatius Loyola, recovering from war wounds, began the meditations which gave rise to his Spiritual Exercises) has as its central theme 'Intuition is the higher form of Reason'. It must surely also have suggested a personal parallel in Beuys's own life. Many artists at the end of the thirties and the beginning of the forties were similarly attracted by science. Where Beuys has proved exceptional is in the continuing strength and breadth of his interest, the magnificence of his grand design and in his use of science, not as a reference, or as a means of presenting something new in art, but as a tool on its own terms both as a practical reality and as a moral one.

What clearly motivated Beuys at this point was his sense of purpose—as he has said, the need to provoke people and to make them understand what it is to be a human being. However, Caroline Tisdall has suggested that full recognition of the role he had to play became clear to him only slowly, and that it seems to have been finalised by a period of trauma Beuys went through from 1954 until the late fifties, a kind of 'Saison d'Enfer', partly as a delayed reaction to certain events in the war, which eventually brought on real physical illness. He lived out part of the darkest period in his life (when again he confronted death and resurrection, as it were in the wilderness, but nevertheless on home territory) on the farm of the van der Grinten brothers, who became two of his earliest patrons and supporters, near Cleves. And it was there that vast numbers of the drawings from the fifties—perhaps the most productive period of all for drawings—were done.

The first event in the chronology which Beuys later made charting the influential events of his life, (and which has been reproduced in numerous publications), is that of the wound drawn together with sticking plaster, signifying the trauma of his own birth. He described it in reference to the sculpture Bathtub 1960 as the wound or trauma experienced by everyone as they confront the hard material conditions of the world through birth, Beuys has made many drawings referring to pregnancy and birth, but if we compare Before Birth, 1950 showing the human foetus as mankind surrounded by the warm, bright waters of the womb, with the hard empty enamel tub with its residue of gauze and fat, we get perhaps the most forceful idea of the extent of that trauma and of the sense of Paradise Lost, at a very particular place and time in the world.

Demonstration of the wound is a theme which runs through all Beuys's work and appeared in public first in 1958, in a project for a competition organised by the International Auschwitz committee. Beuys's understanding, through his own wounds, perhaps, of the traumas which have afflicted our society and particularly the traumas which have befallen Germany in his lifetime, apparently provoked in him the desire to initiate some kind of healing process. It seems to have taken the form of a determination to try to rectify that situation whereby, as in the past, in science and politics responsibility has been delegated to groups of specialists, while intellectuals and artists have remained silent, and ability and creativity have been put to death behind a screen of 'one-sided materialism' and outward progress.

The widespread growth of interest at the end of the nineteenth and particularly in the first decades of the present century in ancient and primitive customs and anthropology had an important impact on Beuys. To initiate a corrective force against the false progress of what he has called 'one-sided materialism' (i.e. life entirely dedicated to the production of material goods — he has nothing against materialism in the wider sense), Beuys chose to present the image of the artist as 'scientist' in its most ancient form.

Always on the look-out for the sources of things, he introduced into his work, almost from the beginning, the parallel between the artist and the Shaman, the healer and wise man of primitive tribes. First appearing in the drawings of the early fifties, the image grew from a private reference to a public one from the sixties onwards — immediately recognisable, above all, by the hat Beuys invariably wears as a kind of symbol of office—as his work developed an increasingly direct relationship with his audience, and thus a need to include the man as well as his output. Beuys has clearly read a good deal about the role of the Shaman and about religious and magic practices in primitive tribes. And as in these tribes, in Beuys's work we cannot see the Shaman and his practices as separate from one another. (The Shaman has to take responsibility for his predictions —he is not only answerable to himself but to society.) However, Beuys has used these ancient parallels in ways which can be generally understood, not as references which need footnotes. It is not hard with the little knowledge left to us to come to at least some general conclusions. In his drawings especially, Beuys goes back to the Shaman's original private function as investigator of the natural sciences, making references to the world of hunting, fishing and farming, but he combines that role with the more complex public one for the good of society, exploring the powers of plants, of drugs and minerals, the phases of the moon, the mysteries of life and death and so on.

While on the one hand one can emphasise that Beuys's work is to do with reality rather than magic, he would no doubt point out that there is more in reality than meets the eye, and that many aspects of our knowledge of it may have their sources in magic. He makes use of aspects of sympathetic, homeopathic or contagious magic, for example confronting like with like, or making a collage of felt (the best is made of rabbit fur) and the toenails of the Shaman as in Moon, 1963. He uses felt and fur in this way in the drawing Tails, 1962, thus in traditional terms retaining his power at a distance. Even his simple use of logic in both drawing and sculpture may be seen to connect with such ancient traditions.

Beuys mixes the practical aspects of magic as an art with the philosophical applications of magic as a science, but without making the references explicit — perhaps they are merely ingrained in his consciousness, the secrets of the power of his images. He seems to aim for references to aspects of ancient lore with which he personally might have been involved, local German fairy tales and folk lore he would have come across as a child, (Siver Coins from the Stars, 1945 Frau Holle, 1957), the Shamanism of the Tartars or other Russian tribes he could have had contact with while flying aeroplanes during the war.

Beuys seems to have felt, realised and enjoyed making connections between things at a very early stage. It seems likely this became a conscious habit about the age of ten, for in his biography under the year 1931 he lists ‘Kleve connecting exhibition’ and ‘Kleve Exhibition of Connections’. Early experiences and ramifications of them recur throughout his career, for the thought processes once initiated seem to be continuous and the ideas inexhaustibly explorable. Inevitably Beuys’s method is part scientific and part the primitive reasoning of the Shaman, part commonsense and part intuition based on in-born heightened sensibility. Through his various exhibitions and actions we have learned to recognise his iconography and the references which have grown up over the years. Nevertheless, these are very tightly controlled. One has the feeling that, as on a stick of rock, the lettering would go all the way through, but only the aspects of his life which are of relevance are available. From this point of view his is the reverse of a personality cult. Beuys is a very secret figure despite his well-documented public image.

Apparently he sensed almost from the beginning that certain aspects of his youthful experience would be of future importance. Heiner Bastian has written poetically about Beuys as a child, trying on the mantle of nature, an image which suggests particularly well the multifarious and all-enveloping aspect of those experiences and the ease with which his receptive brain wove them together to form a magic cloak of understanding, that finally became the huge seamless garment of thought we know today.

The close relationship Beuys felt with the country surrounding him is expressed literally by exploration of the soil (1928 'Exhibition of the difference between loamy sand and sandy loam') and by digging himself into it (1933 `Underground exhibition') which he has connected to his fascination with the hare (and which we shall come back to). It is also expressed by his interest in the growing of plants and the properties of plants, especially healing plants, (1930 `Donsbruggen Exhibition of heathers with herbs'.) The theme of homeopathic medicine runs right through his work.

The earliest drawing in this exhibition is Herb Robert, 1941, made in one of those strange moments of peace at the centre of conflict. Pressed flowers have been attached to a working paper listing therapeutic, oil-bearing plants, made on study leave at the University of Poznan. It subsequently remained put away (like many aspects of the artist's work), to await relevance, until selected for exhibition by the artist in 1980. Although at the time conceived in the spirit of science rather than art, this early drawing may be compared with Therepeuticum, 1964, a list of healing plants where certain of the names have been covered with thick stripes of pigment in order, according to Beuys, to absorb the different substances. It is a usage comparable to that of felt as an insulator and a similar conjunction of felt and chemicals was made in the sculpture Stripes from the House of the Shaman, 1964-71.

Drawings of natural forms were amongst the first things Beuys exhibited after the war, and while studying under Matare in Dusseldorf he made several equating geometrical and plant forms as well as others where the basic lines of an animal—say a sheep or a deer—are emphasised to bring out the simple rhythms and patterns inherent in the form, as in Being Animal, 1948. At the same time Beuys was developing that thin organic line, so characteristic of his drawing style, which seems so specifically 'alive', and also so much more complex and subtle than that of the other students of Matare at that time, despite the strong thematic links between them.

Beuys sometimes refers to plants symbolically, as in several Rosicrucian references, they can also be incorporated in sculpture and in drawings as real things, as substances. Pressed flowers and dried leaves feature in several early drawings, and Beuys experimented with plant juices as pigment both in the fifties — Monument to the Stag,1958 is coloured with rubbed moss—and recently, as in Skulls under Downe House (Charles Darwin's house in Kent). Plants frequently recur in actions, like the fresh red rose for Direct Democracy, which stood in a chemist's cylinder throughout the 100 Days of the Documenta exhibition of 1972, representing revolution, transformation and evolution. On other occasions Beuys has planted carrots in sand dunes and potatoes in West Berlin, and he has demonstrated his interest in the primitive plant life of bogs, in peat and in the rotation of crops as in Runrig, 1973. In Vittex Agnus Castus, an action which took place in Naples in 1972, Beuys's Shaman's hat was stuck all over with sprigs of that Mediterranean shrub, commonly called 'the chaste tree'. The Romans used it in the Temple of Vesta and by Christian times it had become a Parsifal symbol, purging sexual desire and the temptations of the flesh. The drawing Vitex Agnus Castus was made from memory for the director of the Botanical Gardens in Naples, in order to help Beuys find the plant he needed for his action. (This emphasised the two poles of male and female, warm and cold, while drawing them together— another recurrent theme in his work.)

The Shaman played a very early part in Beuys's view of the world. As we have seen, Genghis Khan appeared in his games around the age of eight. Beuys has pointed out that roughly translated Genghis Khan means John Smith, and that he would thus have been a blacksmith in the Mongolian tribes of long ago, a man skilled in the use of fire and metal, and therefore a Shaman. Beuys himself reports an early interest in casting and forging iron and had a cousin who was a blacksmith. The shepherd was another traditional (and equally humble—the aspect of Everyman seems relevant to Beuys's understanding of the concept of the role) Shaman's calling among the nomadic tribes of Eurasia, and appeared at about the same time in Beuys's childhood games. His role as shepherd or stagleader is marked in later work by the staff, crook or walking stick, and apparently as a child Beays carried such a stick around with him everywhere for several years, seeing himself in imagination surrounded by his flocks and herds. (Looking back, the social aspect of it also seems prophetic.)

Communication with powers beyond the human in the simple agricultural sense is described in drawings such as Shepherds Talking, 1974 and The Impact of the Full Moon on the Sower's Head, 1972. In the former, two shepherds, both wearing hats (suggesting a shamanistic element) are depicted discussing their animals, which include a donkey, sheep and possibly reindeer. According to Beuys, the shepherds have interesting matters to impart concerning powers and energies—hence the presence of the bent copper rod or Eurasian staff, used by Beuys in various actions and successor to the original crook or walking stick of his childhood—which leaps actively from the hand of one of the shepherds. They are apparently the cause of this surge of energy for they are connecting with the animals through their brains, by discussing them.

In The Impart of the Fall Moon on the Sower's Head something not dissimilar is happening. Here the sower, again wearing a hat, receives the power of the full moon and transmits it to the seeds below the ground. He is sowing by the light of the full moon because of the beneficial effect on the growth of the plants. The moon is depicted as very tiny and almost integrated with the sower's head, which is virtually a skull. Thus the sower runs along the surface of the earth in an earthly energy field, listening to the terrestrial powers and to the powers of growth beneath the roots (indicated by signs like runes), while transmitting to them the power of the moon.

The drawings Blacksmith I and Blacksmith II, both done in 1958, show the Shaman in a different guise. In Blacksmith II the focus is on a kind of shorthand rendering of the anvil and the fire, which following the wispy intangibility of the images, introduces a spirit clement involving the wind through the use of the bellows. In Blacksmith I we have a more daemonic image. The scene is suggestive of a witch’s cave: the fire roaring up a shaft and the smith looking for something, perhaps an augury, in the brightness of the flames. The result of the smith’s creative activity is visible in his penis, which Beuys has compared to the neck of a swan. The drawing has a more obviously ecstatic quality emphasised by the way the figure is seen in tremendous contrast to the surrounding darkness, and by the fact that it is headless. Beuys took advantage of a piece of torn paper to suggest that by having no head the figure becomes in a sense all head, the head becomes vast, part of the sky, infinite.

Ecstasy in the Shaman’s role appears in several other drawings as in Trance in the House of the Shaman, 1961, Dance of the Shaman, 1961 and Shaman, 1958. Shaman, 1965 has both an ecstatic open mouth and a third eye in the centre of his head like a kind of trepanning; thus the head is an open receiver, emphasised by the receptive antennae on the top, and by the raised hands in the sphere where receptiveness is operative. However in this case the figure is a kind of bird-man, who is perhaps transmitting between the kingdoms of man and animals, having taken on the characteristics of, say, a swan or an eagle.

Communication, as we have seen, tends to be through the head (regarded as — sacred in many primitive tribes) which Beuys often renders almost as a skull with features rather similar to his own spare and skull-like physiognomy. This skullish, bony look may have two rather different references. On the one hand, it may bring the artist or Shaman into communication with ‘the beyond’ through death; on the other it may suggest intellectualising forces which Beuys regards as specifically male rather than female. For example, in The Psychology (Psychosis) of Capricorn, 1972 the human skull becomes increasingly bony until it forms the mountains on which the Capricorn is standing. In sculpture the relationship between the human figure and the mountain is expressed in the bronze Mountain King, 1961. When presenting the female counterpart to this, the huge wooden figure Virgin, 1961, Beuys described the male intellect at its farthest intellectualised peak as a ‘cold, hard, crystallised, burnt-out clinker’,[5] the female always being by comparison less petrified, less tied to the earth.

In order to communicate with the powers of the unseen, with inexplicable or higher forces, or with ‘the beyond’, the Shaman traditionally has to pass, as it were, through the process of death. In Druid cults initiation takes place through the sympathetic magic of surrogate burial in a stone coffin. Beuys has drawn himself several times in this guise, as in Self in Stone, 1955 in The Secret Block... and in the present exhibition in The Cable, 1970.

This aspect of initiation is paralleled in Beuys’s action The Chief, 1964, when he spent nine hours completely wrapped, unmoving, in a shroud of heavy felt. In this form of mock death the artist was accompanied by two dead hares, while from within the felt from time to time he enunciated a primitive cry, like the roar of a stag. Beuys has said that every such action has a radical effect on him, so that in a way through this real situation he is involved in a real death, not an interpretation. Furthermore he believes that only through such a transformation of the self, which takes place through soul, mind and will-power, is it possible for evolution in any person's attitude to take place. Only thus he feels has he been able to become revolutionary himself, and only thus can society be affected — something he feels Marx, in his insistence on revolution in terms of outer conditions, did not allow for.

The hare and the deer are the two most frequently mentioned animals in Beuys's menagerie (though this also includes cats, toads, moose, elks, horses, rabbits, eagles, doves, etc.), figuring in drawings, sculpture and actions throughout his career. The hare has appeared dead in How to explain pictures to a dead hare, 1965, modelled in effigy, stuffed, or stretched on a framework as in Eurasia, 1966, possibly a reference to the practices of Mongolian Shamans. It can be transformed into an inanimate object, such as the Shaman's bag stuffed with powdered quartz in Stripes from the House of the Shaman or merely exist as a skull, or as a tiny jaw bone lying on a gramophone record of one of Beuys's past actions in Seven Double Objects, 1972-78. In whatever the circumstances it retains its special powers, speaking for the artist as for the Shaman. If Beuys speaks through the hare, often it seems he is the hare. The hare running ever westwards from the Steppes exemplifies the principle of nomadic movement across the plains of Eurasia and all the movement of the peoples that has entailed through history. The cycle of birth and death is echoed by the way the hare rejoins the earth by making a 'form' in it (as Beuys did instinctively in childhood), both life and death thus coming from the mother earth—as in its original meaning. According to Beuys the hare is related to the lower part of the body, having a particular affinity with women and with menstruation, the subject of Hare's Blood, 1962. He also compares the hare's moulding of the earth with the processes of human thought and understanding, a process of rubbing, digging and final penetration which transforms the thought and makes it revolutionary. Thus How to explain pictures to a dead hare may be interpreted as a complex discussion about the problems of language, human thought and consciousness. One of the most beautiful drawings of the hare is to be found in In the Morning the Shepherd Saw, 1959.

The stag has features in common with the hare as one of the animals through which the Shaman may proceed beyond death, but whereas the hare represents the lower part of the body, the stag stands for the upper part and the head — the male province. The antlers are its most important feature for they give a record of the entire nervous, hormonal and venous system throughout a yearly cycle, and represent the inner feeling or soul of the animal. Traditionally endowed with special spiritual powers the stag has a closer connection with death than the hare. It often appears at times of death or danger and according to Christian symbolism, when dead, represents the misunderstanding and sacrifice of Christ. Many of Beuys's drawings of stags such as the two Monuments to the Stag, 1958 and 1959 relate to that time in the fifties when he was most obsessed with the idea of death, though also meditating on the phenomena of existence and of evolution. Beuys has always made it quite clear that he does not 'use Shamanism to refer to death, but vice versa — through Shamanism I refer to the fatal character of the times we live in. ... But at the same time I also point out that the fatal character of the present can be overcome in the future.'[6]

The presence of the Shaman is not recognised by his own image alone; the emblems of his trade can be equally significant. The grey felt trilby, for example, with which he insulates his energetic and receptive brain. A hat on a shepherd or a dwarf can signify the presence of the artist, as indeed can any hat, perhaps, even the shining gold Jockey Cap on the Grass, 1969. The images of the staff, or of deer or hare, equally suggest the Shaman cannot be far behind. Just as Beuys made a Shaman's bag from a hare for Stripes from the House of the Shaman he also drew the Shaman's material, Houses of the Shaman, 1965, the Shaman's Two Bags, 1977 and the Stagleader's Cart, 1976. Both the latter seem like ceremonial, cult objects but are also peculiarly organic. The last suggests by its antler-like forms that it is in fact capable of running on its own energy. (One gets the same impression from the Jockey Cap.)

One cannot talk about the image of the Shaman, who is male and represents the artist himself, without mentioning the role of his female counterpart. Beuys uses a male image only in a specifically masculine context, such as a sexual context or as the over-intellectualised concentration on the powers of the head, or in reference to the spirit of Mars, as in the sculpture Tram Stop, 1976. Where the image of the man appears to be mineralised and static, that of the woman in Beuys's work is more fluid and active and he believes women have a greater openness to the possibilities of the future. Women are frequently shown running, leaping, squatting, carrying bags of necessities, sticks, stones, filters; for example Woman with Sieve, 1960, Girl with Bag, 1956, Freckled Frogs, 1958 demonstrates well both this active role and their more watery connection.

Women are also often presented as actresses (Actresses, 1958). Witches Spitting Fire, 1959 comes into this class. The sense in which Beuys regards them as actresses is in terms of 'performance, of the kind he himself is involved in in his 'actions, not in the sense of reciting Shakespeare on a stage. (Indeed this drawing hints at the whole alchemy involved in performance through which Beuys has transformed science and developed possibilities for the future forms of art.) Traditionally the Shaman is often confronted by witches, by elementary spirits, giants and so forth, and one suspects that these particular witches may have come out of the Shaman's furnace. Just as women tend to take the heroic position in Beuys's work, they often suggest an androgenous connection and these particular women seem to have a large proportion of Mars in their characteristics. Male and female often join in other contexts, for example Stag Woman with Felt Sculpture, 1959 or Girl with Staff, 1958. Beuys has even thought about himself as pregnant in While I was Pregnant, 1951.

Another area where male and female elements sometimes fuse is the image of the swan, as Swan Woman, 1958 and Pregnant Woman with Swan, 1959 both demonstrate. The swan cults of the Lower Rhine appear to have made a deep impression on the artist as a child. The medieval legend of Lohengrin relates to precisely this area, but Beuys's interest is less to do with mythology than with a kind of empathy with the bird as an inhabitant of a particular geographical area, and with a recurrent childhood psychological experience, or kind of waking dream, connected with the golden swan which, until the Second War, topped the Schwanenburg Castle in Cleves, and which at the age of four or five Beuys could see from his house across the steeply sloping roofs of the town. The presence of this bird seems to have inspired in him a sensation of the need to make use of the powers of the head, and an understanding of what by doing so it meant to be 'Prince of the Roof.[7] The climax of this vision is probably the sculpture dernier espace avec introspecteur, 1964-82.

There are many representations of swans in Beuys's drawings, including a whole series entitled The Intelligence of Swans, and several swan images are to be found in this exhibition. In The Cable the swans are also included in the context of a medieval street scene, perhaps a reminder of Beuys's childhood in Cleves. Swans' necks, forever dipping beneath the surface of the water for nourishment suggest a parallel with the human energy of the backbone-like cable flowing beneath the earth, and that both derive energy from that source. As with the hare or the deer, Beuys (the Shaman) is the swan; in each case he can in a sense be said to take on the personality, perceptions and habits of these creatures, thus each time sharpening our view of a mental, spiritual, moral or physical (often sexual) idea by the comparison. The trace of actual hares' blood on the drawing of the sexually available young girl, the woman whose neck has become a swan's are both good examples of Beuys's Zeus-like disguise in operation.

The close relationship between artist, the swan and the countryside of his birth is expressed with poetic force in Pregnant Woman with Swan which depicts a tiny swan swimming within the body of a woman, taking the place of a male organ (the comparison already made in Blacksmith I) or foetus. The very word for pregnant in German, ‘schwanger’ seems connected. The external form is rough, primitive and earthy, and looks like an outline map, a jug, a kernel in a nut or an ancient fertility symbol such as the Willendorf Venus. The contrasting watery image of the swan inside is depicted with enough suggestion of horizon to give it a spatial orientation. (A similar composition to Bermuda Triangle 04.00 Hours, 1959). The themes of birth and return to the earth we have already discussed in terms of the hare are also echoed traditionally in the Leda mythology. However here the theme of regeneration through the earth is given a particularly terrestrial aspect. The unity of the image also perhaps contains a reminder that the swan only takes one mate in its life. This is a union of Mars and Venus, but as in many of Beuys’s drawings the principles have been reversed.

The sea creature or fish is another image often used by Beuys, which also has parallels in the magic of primitive tribes. A related use of metaphor to that in Pregnant Woman with Swan can be seen in Angel Whale, 1953 which demonstrates how Beuys disentangles and fuses layers of reality and non-reality, in this case to form the traditional connection between the seas and the heavens, between the largest mammal of the deepest earth and the spirit of the highest skies. He even draws a kind of hook or trap for the creature, a sign of ever present danger, perhaps invoking the ancient custom of using fishhooks to catch souls in certain tribes (compare Whale Trap, 1966. Angel Whale was made at the time when Beuys was working on a series of animal reliefs in slate, in the course of which he also made numerous drawings of fish, sea cows, seals, whales and so on. Two Red Fish, 1954 belongs to the same group, but unlike most of the drawings which were very small and painted with blood, this image is relatively large and painted in brilliant cinnabar red—a primal colour, which is the basis of mercury and like the fish a symbol of life.

The fish is also a symbol of continuity and represented in Beuys’s theories about man’s place in evolution. It appears along with the seagull, the snipe and the goat in the construction drawing Evolution Beuys made for his children in 1965, to explain how these creatures cannot escape from their fixed point in evolution, whereas mankind can. Moreover, since evolution is a fixed but continuous process with man up at the front, it is not only for man to speculate about the direction is which he is moving, but about how he can affect his destiny.

Beuys’s research into the patterns which make up the whole process of evolution has led him to try to regenerate perceptions long lost, through contact with the animal kingdom, the scientific exploration of the substances of the earth, through the traditions of the past (the Shaman) and increasingly since 1960 through direct contact with the human beings who make up today’s society. It seems that what Beuys is trying to do is to make us see exactly the nature of our position, to show us what we have lost by our particular degree of civilisation (closeness to nature, intuitive powers, ancient lore, irresponsibility and so on); and what we have gained: materialism, increased intellectualisation and ostensible freedom from the rule of the Shaman — but it is both freedom at a price and freedom which has to be fought for. As Beuys points out ‘there are no such things as unshakeable principles – everything is alive and in flux’.[8] The only laws are created by man, and he too is in flux.

Thus if he uses Shamanism deliberately as an incongruous primitive element in our society, by the same token it is clear to society that Beuys can be no more than a metaphorical Shaman, since Shamanism no longer exists. However, as it no longer relies on the Shaman for guidance, society is faced with another problem: it is free to control its own destiny and indeed must have a moral responsibility to do so. The image of the Shaman Beuys has adopted reflects our precise place in the scheme of evolutionary development. We see ourselves and our rulers reflected in primitive societies and see to what extent the Shaman still operates in a modern situation. That gives us a view of our rung on the ladder.

Perhaps the little drawing Dwarf, 1965 sums up Beuys’s view of this position. He regards it as a self portrait, and it depicts a very unpretentious, primitive, ugly, little creature in a hat (a cave wight, the artist has suggested) digging away very fanatically, in one hand a twig or root, the other protected from the energy generated by his spade with a scrap of felt. Wolf Vostell’s quotation of Tagore in another context seems relevant: ‘The burden becomes lighter if I laugh at myself’.[9]

In a nutshell and with scientific modesty Beuys demonstrates his position on the evolutionary scale and defines the nature of his activity. He is always digging away, not only industriously but fanatically, where maybe no one else has thought to dig before. His purpose is to get to the truth and to help society. He is not concerned with beauty, with painting beautiful pictures, or with playing games to do with art; he is only concerned with digging, a primary activity, because the truth, the reality, is more important.

Beuys has made it quite clear that he is interested in ideas and not in artistic or scientific activity for the sake of it: ‘I’m interested in ideas that are there in reality. I want to create a new space for this idea. I don’t impose my own personal stylistic preferences on things in any way... The object has to say something to me first. If it doesn’t say anything to me, I wouldn’t sit down and draw it. I don’t sit down until there’s a necessity, until something says something. If nothing does, I don’t draw.’ [10]

Beuys’s enormous advantage is that he came to art from the outside and he determinedly remains outside it — because it is too important to him. A group of drawings such as this offers an extraordinary opportunity to examine how his creative mind draws together ideas from reality at various levels. Each of his works is involved with a complex ‘constellation’ (as he often puts it) of ideas and a special excitement attaches to the drawings as they are often the first and most direct evidence of the artist’s thinking.

Although the appearance of a drawing is not of first importance to Beuys, its colour or substance are likely to have some sort of relationship with its subject or meaning. Beuys uses materials in drawing very much as substance, and in ways comparable to how he would use them on a much larger three-dimensional scale. The fact that he frequently uses ordinary or unimportant materials is not so much a matter of principle as a matter of suitability. Thus a material will tend to be the real thing or an equivalent for it and it will certainly make a point. Choice of what might be seen as ‘arte povera’ materials in his work certainly does not have its origin in art at the beginning of the sixties or with the Fluxus group, but goes back much further. The drawings parallel the progress of the sculpture. From the fifties substances such as fat, felt, copper and iron used in the sculptures and actions are referred to increasingly in the drawings, and occasionally actually incorporated into them. Some of the drawings from the end of the fifties get to look more ‘scientific’, for example suggesting the look of chemical apparatus, electrical batteries, Faraday cages and so on.

Colour is frequently used as substance, and even if it appears to be used quite traditionally, a closer look will usually provide a precise meaning supporting the total idea. Red, for example, appears rarely, but when it does, it is used deliberately as in Two Red Fish. The use of red in Hearts of the Revolutionaries, 1955 seems self-explanatory, but it also has another title which makes the choice especially suitable: Passage of the Planets of the Future. Blood is used in many drawings of fish thus doubling and opposing the symbol of life. It is also used in a drawing of a young girl —a smear of hare’s blood suggesting the menstrual cycle. Chemicals (iron chloride is a favourite often included with watercolour) and chemical reactions as well as organic liquids, flower and plant juices, have been used as a means of making drawings without artist’s pigment, for example in Before Birth, 1950, Two Girls, 1952, Druid’s Measuring Instrument, 1961. Metallic paint has been employed in studies for sculpture (Gold Sculpture, 1956), and to equate like with like in another way in Flowing Water, Health of the Mouth, 1951. Even when the medium is primarily traditional, like watercolour, there may well be a connection with the idea Beuys is presenting, as with the watery aspects of Before Birth.

Sometimes a colour may be chosen deliberately so as not to have any other connections, especially with art. Beuys’s use of the mysterious ‘Braunkreuz’ is a good example of this. This is an oil paint he first discovered in 1958 when trying to cover a cross form with a colour which would have no meaning as such. He tried various grays thinking that, like felt (which operates in negative suggesting colour by its neutrality and sound by its muffling qualities) this would achieve the desired result. But the only colour which seemed to work as he wanted was a common brown used for painting floors, and because of his original need he renamed it ‘Braunkreuz’. It has been used in drawings ever since, mostly sculpturally in large solid areas, more as substance than colour, for example Energy Field, 1962 or For Felt Sculptures, 1964. The inference that this is very much a sculptor’s approach to working on paper is emphasised by the grounds Beuys uses for drawings and the way he incorporates collage or mounts several sheets together into a single image. Although the choice of ground may be haphazard in the sense it is not sought after — maybe torn or already used bits of paper, the cardboard backs of old notepads and so on—it may trigger the expression of an idea. However, whereas it is the original conception which finally holds the key to the drawing, rather than the substances which help to make it visible, the final swift interaction of energy between artist, substance and idea is one of the things that cause the drawing to come alive at the moment of making. Obviously this is a truism about all art, but in Beuys’s work one has a stronger sense than usual of the relevance and material evidence of this, as well as of the consciousness of the artist and of thought processes expressed in terms of performance.

If a need to represent an idea or image which is alive is basic to all artists, Beuys makes assurance doubly sure through his concept of energy and its importance, whether contained in the powers of electricity or magnetism, thought, conversation, metamorphosis, earthquake, biological or spiritual changes in birth, death and evolution, or in matter generally — from tables to mountains, from a jar of pears to a glacier. Beuys is not so much interested in the energetic aspects of individual substances as in how they can be used in one of his ‘constellations’ of ideas. At the end of the forties Beuys had already begun to formulate his Theory of Sculpture, which was later to be embodied in the sculpture SaFG–SoUG, 1953–8 (short for sunrise – sunset in German). This work demonstrates his conception of the passage of chaotic matter through sculptural movement to ordered form, a passage from warm to cold, paralleled by the formation of the earth and the processes of evolution. Beuys seems to have found confirmation for his theories in those of Rudolf Steiner, especially as expressed in the 9 Lectures on Bees. Numerous drawings, such as Bee, Old Woman, Pregnant Woman 1954, Bee, 1970 or Queen, 1962, as well as sculpture from 1947 onwards, illustrate the artist's continuing fascination with the bee’s production of honey and the social structure of its communities. In Beuys’s work the theme is always connected to the idea of warmth, with metaphors for natural and social behaviour and analogies for physical and spiritual production.

He has said that what interested him primarily about the life system of bees was the total aspect of heat or ‘thermal’ organisation and the sculpturally finished geometric forms resulting from it. In sculpture the fluid and crystalline elements of honey and bees-wax are used directly as material culminating in the great heap of bees wax on the shoemaker’s (Shaman’s) chair in dernier espace avec introspecteur, 1964-1982 and in the Honey Pump, 1977 which demonstrated the principles of the Free International University working in the bloodstream of society.

The principles of Beuys’s Theory of Sculpture are manifest in countless drawings, but three examples give some idea of the range of ways in which it is possible to interpret these ideas. Granite in Arid Chalk, 1965, is a good example of an idea based on the opposing poles of hot and cold, in this case beneath the surface of the earth and operating in a geological context which, having a power to influence growth in particular ways, should be taken into account in agriculture. This drawing involves diametrically opposed elements, which also operate in reverse. The bone-like formation of the chalk contrasts with the obelisk-like clarity of the granite. What looks like fire (the red granite) is however the cooler of the two elements, while the whiter chalk or lime, which might be said to represent water, is in fact the warmer substance. Pregnant Woman with Swan works in a similar way.

In Pressure-Current Insulator Metalveins, 1960 Beuys is concerned with opposing forces in a different way. Here we are also presented with a sculptural parallel for an idea and the idea itself. For here, as in the Fond sculptures, Beuys opposes the passive insulating qualities of felt with the active conducting energy of a metallic substance such as copper. The drawing shows close up and long distance views of the earthly landscape; the distant view has a tiny moon in the sky, the close up reveals the metallic elements within the earth: gold, silver, tin, mercury, etc. A mountain range marks the border of the discussion of these two states, which concerns not only the visible and invisible, but also the unmaterialised and materialised conditions of energy and two different spiritual states. The terrestrial sphere is characterised as a hard crystallised, metallised state, the other as still fluid and embryological. The two states are joined by a ‘line of transformation’ which rises out of the invisible towards the visible; and the energy in warmth, which penetrates into the upper sphere resulting in new material conditions, creates a fusion of materialised things or causes dematerialisation of the present material state. The flow of energy and the pressure which builds up is indicated by the words ‘Fluss’ (flow) and ‘Druck’ (pressure). Cross forms allude to the Christian ethic which has been important both to the process of spiritualisation and materialism on earth.

The third example is a series of three drawings, Energy N1, T2 and M3, 1971, which discusses three different kinds of energy. The first drawing (marked N for neutral) signifies a neutral discussion involving the material alone—the principle of life. The second (marked T for ‘Tier’ — i.e. animal) concerns the animal kingdom and introduces the principle of the soul; the raised hands express the soul of the animal and its crying need for help. This middle position of the theory of sculpture marks the aspect of feeling between will-power and thought. It is represented by three hearts, which indicate the aspect of feeling and movement and also the central position in this constellation of energy. The last drawing in the group (marked M for ‘Mensch’ - i.e. man, human being) represents the possibility of intellectual discussion through knowledge and consciousness of all the possibilities of energy, Beuys described this by depicting a kind of earthly goddess. The earthly aspect is expressed by the fact that the goddess is shitting, but by doing so she instigates a new earthly link and thus the possibility of higher progress in the future.

Beuys’s Theory of Sculpture developed in the sixties to include Social Sculpture, which extended the definition of art beyond the activity of the artist to include the creative talent of every individual, thus paving the way for a society of the future based on individual creativity. It then grew again, as expressed by a huge blackboard drawing Energy Plan for Western Man, 1972, and related drawings such as The E-Plan for the W-Man, c. 1974 to evolve the principles of the Free International University, calling for a regeneration of thought throughout the world which would produce an alternative to both Eastern and Western forms of capitalism, and a free democratic socialism which would operate through the people, instead of a party system based on the forces of money and power. These are the bare bones of Beuys’s thinking about the establishment of a new social order. The drawings, actions, lectures, sculpture and political activities fill in the flesh and reveal just how complex Beuys’s work has become.

The radical transformation of the social order is the primary concern of Warmth Time Machine, 1972, one of several drawings on the same subject at this time. Beuys begins his arrangement in the cultural sphere. The drawing first of all concerns his theory of Social Sculpture, which relates to everyone’s creativity and labour and is thus part of the move towards the wider understanding of art. He then introduces the two main areas of the body politic, the economic system and the legal system, which secures it. Here Beuys discusses the condition of labour within the capitalist system and proposes a new credit system and a new democratic banking system, which works with (instead of against) nature to preserve it and to develop quality for the future. Thus the general structure of the drawing is as follows: at the top are the principles of freedom and self determination as expressed by a pentagram or star. (From Beuys’s point of view the true symbol of Christianity, being both dynamic and static. Rudolf Steiner had similar views on the central importance of Christianity and considerably influenced Beuys’s social and political theories). At the bottom is nature with all its resources. And in the centre is the discussion of our present state of culture which is based on the idea of capital and the use of money.

Linking the three areas of the drawing is a kind of line of time, similar to the line of transformation in Pressure-Current Insulator Metalveins. This puts Beuys’s ideas in historical perspective offering a kind of simultaneous equation with, or contemplation of, historical events. Transverse lines indicate the middle of time and the year zero of historical time, which Beuys takes as the beginning of the Christian (socialist) Impulse, which being principally concerned with humanity, instigated the overthrow of the old order of nationalistic culture. More than half the drawing is made up of words, words such us ‘Unternehmen’ (enterprise) ‘Wirtschaftsystem’ (economic system) ‘Rechtsystem’ (the law) ‘Kreditsystem’ (banking system), Incarnation and Excarnation. Beuys also uses the rubber stamp, dating from the early sixties and used for all his actions which includes the symbols of earth and Christianity surrounded by the word ‘Hauptstrom’ (mainstream), indicating we should concern ourselves with the main problems — in this case capitalism, socialism and Christianity.

The purpose of the drawing is essentially to contain the argument in the most succinct form possible. The use of words in drawings becomes more frequent from this period, but Beuys also includes other kinds of language, such as small signs indicating factories, a calvary with three crucifixes, a serpent indicating Paradise Lost, or a triangle to indicate the discussion of form in art. Reference is made to the problems of painting and sculpture — namely those of line and colour, form and figuration, light and shade, and to the need to retain the aspect of craftsmanship in the arts, to retain the special abilities of the people and the traditional idea and satisfaction of working very closely with materials in a workshop. Such ideas could be used in relation to any profession, Beuys takes the artist’s because that is his point of view. Thus at the end of the fifties and beginning of the sixties Beuys got closer and closer to direct involvement between himself and the social context in which his work was being produced. It was not a purely personal movement, more a world-wide one, which gave rise to many different manifestations including Pop Art. In 1962 Beuys made contact with the Fluxus Group, an international mixed bag of artists and musicians, (especially musicians), who were interested in broadening the concept of art in the general sense and bringing it closer to the public. Although he used his relationship with the group for his own purposes and in many cases did not agree with the ideas of the other members, the performance aspect of Fluxus extended Beuys’s field of activity enormously.

In drawing the effects are felt in a new category — the ‘Partitur’ or score for an action, which later developed into the ‘partitur’ for a lecture like Warmth Time Machine and which is related to the Plays of 1961-3, that came first. As well as full-scale scores of this kind Beuys would also make many other drawings in connection with actions, ranging from the more general, like the shamanistic Fluxus Instruments, 1963 to drawings for various, specific actions, such as Score for Manresa, 1966 or Vitex Agnus Castus, 1972. Beuys’s interest in the structure and meaning of language and in music and sound in the context of art as a language were much developed by his work in this context. One of his strongest youthful talents was literary, and had he not turned to science and art, he might well have ended up a writer. His exploration of the energies of sound and language involved working with musicians, using animal as well as human modes of expression and studying the origins of the German language. The series of drawings entitled Words which can hear, 1975, was made in the context both of this research and of his role as Shaman, and remains an on-going preoccupation, the most recent drawings in the exhibition, the 16 part To Mikis Theodorakis, made at Christmas 1982, demonstrate the same concerns.

Just before his liaison with Fluxus began, Beuys was appointed Professor at Dusseldorf Academy of Art and this, as well as the consequences of his movement into the sphere of ‘action’ and performance as well as sculpture, and his theories leading to the further development of Social Sculpture, resulted in increasing involvement with the student predicament and education as such. These were the years when the student movement developed all over the world, erupting with particular force in 1968, and which also saw the rise of the private pressure group as a force to reckon with.

This is not the place to describe Beuy's’s expulsion and final reinstatement at the Academy or to discuss the huge number of public events in which he took part during the sixties and seventies. However it is significant that though he continued to make drawings for sculpture, and other reasons, from the mid-seventies onwards, by far the larger proportion of drawings is concerned with theoretical structures. They are scores for actions (which in turn often give rise to sculpture) and analytical structures describing the social movement of which he is part and where he has established political organisations, such as the Organisation for Direct Democracy or the Free International University. Many of the drawings for Honey Pump, and for the ecological movement (partly embodied in the Green Party, of which he was a co-founder) were done in the style a teacher might use on a school blackboard. Often they were very large, moving across several blackboards at once, in order to get in all the related points of his constellations of ideas and thoughts about possibilities for the future.

Beuys’s sculpture, his drawings and actions all show the same process of thought and the same drive to widen the area of research, when all about him the tendency is ever towards narrowing and specialisation. Perhaps no one achieves everything he sets out to do because of the fluid nature of the situation; but one thing is clear, we cannot now, being warned at the outset, fall into the error of specialisation and regard Beuys’s work simply as an advanced form of art.

If it relates to anything, perhaps Beuys’s scientifically based attitude goes back to the age of German Idealism, to Novalis, to Goethe and his circle, and then to later followers such as Rudolf Steiner. Encouraged by the Allies the postwar period brought a great resurgence of interest in the golden age of German culture. However, just as Beuys has not closed his eyes to the traumas of the recent past, he can also be much tougher than his antecedents in his cultural judgments. Whereas in Hegel’s view he might not be considered an artist at all, in Beuys’s opinion (the digging dwarf). ‘We haven’t arrived at art yet’,[11] and what will happen one day will be greater than anything we have ever experienced.

Within art Beuys has been peculiarly influential from the beginning, even as a student he was obviously one of those who affect the others. His own students have included important younger artists in all fields of action, by no means all of them sculptors; artists as different as Kiefer, Rinke and Dahn, for example. His presence is felt in many areas of sculpture, but often younger artists from all over the world, who are not sculptors, can also be seen looking over their shoulders at his example – from Clemente to Schnabel. Even by reacting against the inevitable academicising of his work by second generation teaching, the young ‘Wild’ painters of Germany have not entirely shaken him off. The reason for all this is not to do with style or medium but with ideas.

Beuys also has a particular role in Germany outside the specialist art context. Active in so many walks of life, transcending the gulf between youth and age, he seems to have given that society a sense of balance it would not otherwise have had. There have been other great minds in Germany who integrated art and politics— Bertolt Brecht, for example, inventor of the theatre of the scientific age. But although Brecht was fascinated by reality and by the world he wanted to change, his was a love-hate relationship. Further he was neither practical nor visionary — Beuys’s devastating combination. Perhaps more than any single person in postwar Germany, Beuys has given those who want to listen a sense of freedom, a solution not based on materialism, but on the power of thought.

Self determination and human liberty are basic questions of art and Beuys has admitted that at bottom this is the context of his drawings. The free human gesture is always there as a reminder ‘even if all you see is a jockey’s cap on the grass’.[12] With Beuys inevitably we connect a hat, wherever it is tossed down, with the artist. The hat makes the Shaman’s point, states his position. Yet in Jockey Cap on the Grass, 1969 more artistic even than the old grey felt, the mood is more lyrical. The cap is a tiny symbol of speed, skill and pleasure. Perhaps it contains a suggestion of mortality — if so it is even stronger for not being personalised, and because (like the moons he draws sometimes) it is so small and fleeting despite its hieratic presence. In their conversation of 1979[13] Heiner Bastian reminded Beuys of the two principles of Goethe’s Faust — on the one hand continual searching of consciousness in all directions, on the other ‘verweile doch’ (stay a while), the perfect moment of happiness, and Beuys equated this with the Jockey Cap.

Notes

1 Götz Adriani, Winfried Konnertz, Karin Thomas, Joseph Beuys Life and Works, Barron’s 1979 (first published in German, 1973, Dumont Schauberg Verlag, Cologne) p.54

2 Heiner Bastian and Jeannot Simmen, Interview with Joseph Beuys, in the catalogue of the exhibition Drawings, National Galerie, Berlin, Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam, 1970-80, pp. 93-94

3 Ibid, p. 101

4 Ibid, p. 96

5 Caroline Tisdall, Joseph Beuys, catalogue for the retrospective exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, 1979, published by Thames and Hudson, p. 50

6 Heiner Bastian and Jeannot Simmen, op. cit., p. 94

7 Caroline Tisdall, Joseph Beuys, dernier espace avec introspecteur 1964-82, Anthony d’Offay, London, 1982

8 Heiner Bastian and Jeannot Simmen, op. cit. p. 95

9 Caroline Tisdall, op. cit. (5), p..94

10 Heiner Bastian and Jeannot Simmen, op. cit. p. 99

11 Ibid, p. 97

12 Ibid, p. 96

13 Ibid, p. 99