Joseph Beuys Interview about key experiences: Georg Jappe

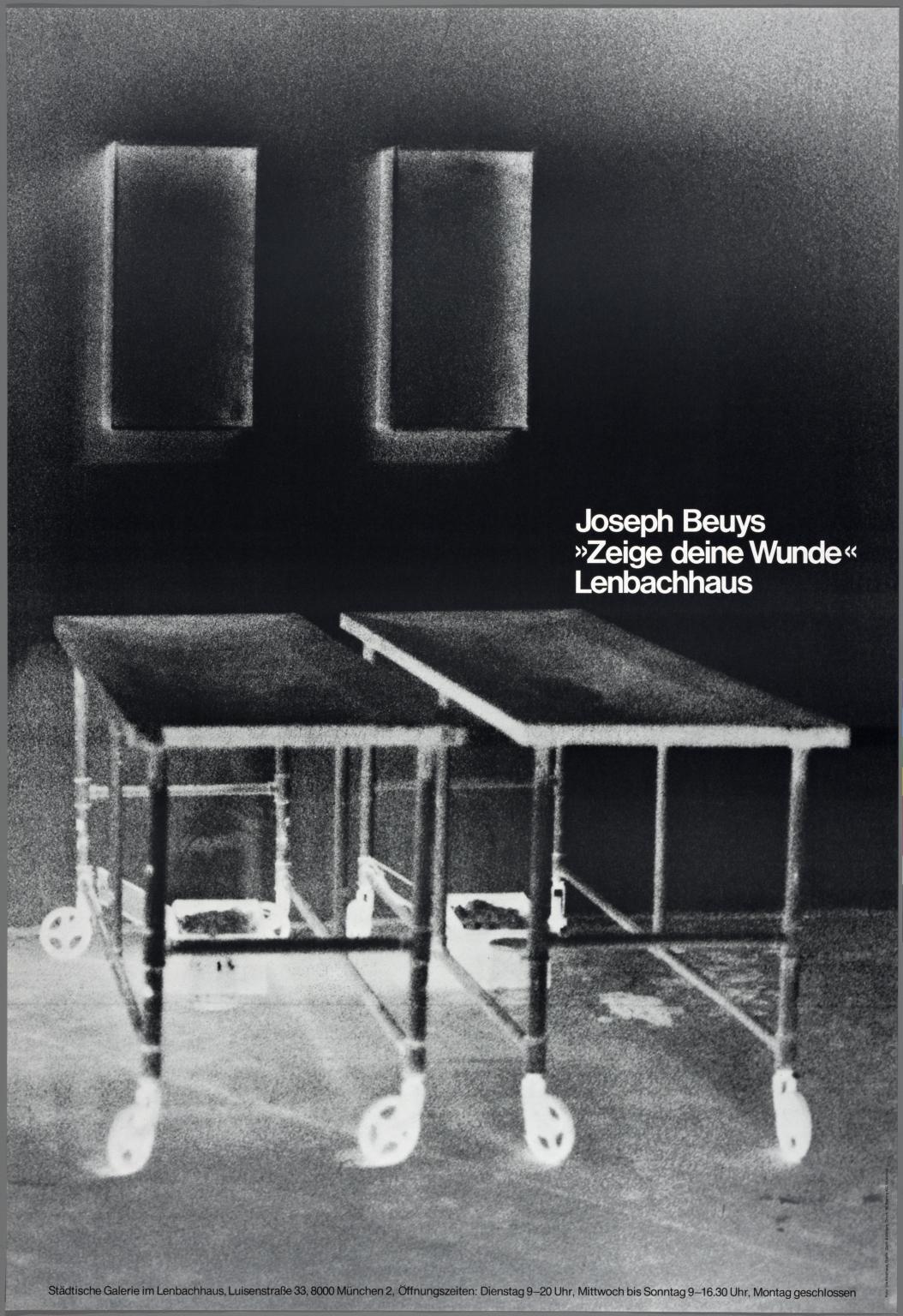

Joseph Beuys: Seige Deine Wunde (Exhibition Poster)

BEUYS: Key experiences come in many different forms. For example, wholly external key experiences-practical life encounters with various matters can become a key experience, but there are also obviously key experiences which, how can I put it, have an almost visionary character, say childhood or eidetic images, or . . . one can even have key experiences in dreams, and well I’ve had quite a few such key experiences. (Pause.) But I think it's always right to start with the practical, that is factual, key experiences. Those that arise somehow from working.

One can also say that true key experiences always inherently have something experiential about them in the broadest sense, something that cannot be purely accounted for by rational cognition. Anyway, in the consciousness of a human being with a completely rational stance towards life, these experiments often appear as something mythical, graphic or simply put, as something mythological. I believe that key experiences of the second kind, those that happen in childhood or up to the age, say of fifteen, are often far more decisive than external key experiences later; or that decisions which are made in connection with later key experiences – say in a work situation where one has decided to proceed in a certain way and discovers that it's not going to work out – these decisions link up with key experiences which lie much further back and exist in a wholly different, let's say a spiritual stratum. (Pause.)

Anyway, my most important key experience as far as work or method is concerned, came when I made the rather spontaneous transition from an interest in science to an interest in art. Let's say quite simply that I experienced the feeling of being forced by a specialized concept of science into a particular field of work, as no longer a possibility for myself. Let's assume that I had decided, embarking on a general study of science, as I did, to specialize in chemistry; then, at the next crossroads in this field, I would of course have had to proceed to yet a narrower field, and then again from this narrower field to another narrower one at the next crossroads, and so on, until, had I become a good chemist-and I always stress, had I become a good one-I could have become influential and effective as a leading authority in a very narrow scientific field. That was a real anxiety experience for me during the war. When I got a study leave as a soldier – you could do that then – during which I attended a few lectures at the Reich University in Posen (which might have been an opportunity to be completely excused from duty at the front through so-called scientific service, as many people I know did),

I began to say to myself that I must have this worked through by the end of the war; that I must decide science or art?

JAPPE: And where did you have the experience where these things became clear for you?

BEUYS: I experienced it as a shock, quite graphically in a professor's lecture about amoebas. There are these microbes that exist on the border between plant and animal Life. And I experienced the fact that this man devoted his entire life to a few small animalcule-like creatures. That terrified me so much that I said: No, that is not understanding of science. It was this . . . image of the amoebas, it still recurs again and again today. I literally still see the black board with these few little animals. I wasn't very old then, I didn't incorporate this into a conceptual scheme, I just experienced it!

When I later studied at the art academy here, I saw that the concept of art is equally limited. That was another experience, being sent to a particular teacher. At that time, you were still assigned to a teacher. You were received in a very friendly manner at the door, unlike today. On the first day as a student, you were greeted warmly by the Director, and as in those days you didn't yet have the opportunity to choose your teachers freely (the entire academy was burnt out, with no roof, and you could see through to the sky), you were allocated to specialized classes. "Go to Room 20," where my class is now, he would say. "Go to Professor Mages." I went, and he was just coming out of the door; I turned on my heels (laughs). "OK:' said the Director, "then go instead to this other one, to Mr Enselinig." Well, he approached me almost like a surgeon, wearing a white smock, with modelling tools instead of a stethoscope like a doctor. It felt like going into an operating room. This experience-finding in art another specialist. With him it was pure academicism, drawing the human figure with constant reference to the musculature. He would say, "Look, you haven't got the muscle right at all," then he would tap on the studio model, on the muscle. As if art could be built up from the muscle.

Enseling was always very nice, though I presented him with things that drove him to despair. At times like that, he would always say something like, well, I know almost all sculptures, but I've never seen one like that (laughs)-he put it so naively! Or, on one occasion, I took part in a competition for a fountain which he had announced. And what I submitted really wasn't very adventurous, but it had free forms; and he said, " I know almost all fountains, Mr. Beuys, but I've never seen a fountain like that!" (laughs.) But that was a judgment for him, because a muscle just doesn't exist in that way, i.e. what I had done was wholly off the mark. Halfway through my studies, I made the effort to transfer to Matare, who had some freer views about art; that was like a revolution for me.

JAPPE: Well,what's the story here? It is often said that the flying vest, fat, felt, were all inspired by the crash and the Tartars tent where you were cared for . . . wasn't that also a key experience?

BEUYS: Yes, of course! That lies on the border between the two types of key experiences. It was also a real event. (Pause.) Without theTartars,I would today not be alive. These Crimean Tartars were behind the front. I already had a good relationship with the Tartars. I often went to them, and sat in their houses. They were against the Russians, but certainly not for the Germans. They would have liked to take me and had tried to persuade me to secretly settle down with some clan or other. You not German, they would always say, you Tartar. Implicitly of course, I had an affinity to such a culture,which was originally nomadic, though by then partially settled in the area.

Then when I had this crash, and they hadn't found me because of the deep snow, if they hadn't accidentally discovered me in the steppe while herding sheep or driving their horses... then they took me into the hut. And all the images I had then, I didn't have them fully conscious. I didn't really recover consciousness until [approximately] twelve days later, by which time I was already in a German field hospital. But all these images fully entered into me then. In a translated form, so to speak. The tents . . .the felt tents they had, the general behavior of the people, the issue of fat, which anyway is like . . . a general aroma in their houses . . . also their handling of cheese and fat and milk and yogurt-how they handle it, that all in effect entered into me. I really experienced it. You could say, a key experience to which one could forge a link. But of course it's a bit more complicated. Because I didn't make these felt pieces to represent something of the Tartars or, as others say, to represent something that looks like a concentration camp mood, gray blankets . . . that plays a part of course, that is what the material itself brings along with it. Especially when it is gray. But those are all admixtures. Later I took felt and tried to insert it fully into theory. As an insulating element.That adds a theoretical element. But I probably would never have come back to felt, without this key experience. I mean to these materials, fat and felt. Just as I would also, without my inner conditioning, never have come to these people and to such a sphere of life. So one can trace it all further and further back, but the real experience with the crash, that was definitely very important for me. (Pause.)

JAPPE: Did you actually experience the crash, or was it all so quick that . . . ?

BEUYS: No, I experienced going down. I said let's all bail out. Then I probably said briefly, I'm not a hundred percent sure, that there's no point any more, because we were already, the altimeter had failed, and I could judge this by instinct that, if we had jumped, the parachute wouldn't have opened. But I don't really know any more. When I said that, the impact came probably two seconds later.

JAPPE: And that you didn't. . .

BEUYS: No, not at all . . .

JAPPE: And there were others in the plane?

BEUYS: Yes, one other. It was always a two-man crew.

JAPPE: And he . . . he died?

BEUYS: Nothing could be found of him. He was atomized. Basically, one found nothing but small bone fragments. Everthing else was pulp in the cockpit because he had the bad luck to be strapped in. I hadn't . . . actually, I never strapped myself in. (Pause.)

I always wanted to have freedom of movement. And I had only one belt, in which one could move forwards and backwards. And this belt must have torn at a very opportune moment, when the plane impacted. And as it tore, the cockpit canopy slipped off – it was a sliding canopy – slipped down, and I went out with it, and then onto me came the entire tail section of the plane. So basically, I came down at the same velocity, no longer fastened into the plane, but next to it. Otherwise, I'd have been . . . there'd have been nothing left of me. Well, then I – they, I did just experience them, hearing voices, these Tartars, and rummaging in the metal, which . . . lay over me, and how they found me, and were standing around me, and then I said "woda:' i.e. water, and then everything got interrupted. (Pause.) Well, all that just to introduce the sequence of events, why I survived what normally no human survives. (Pause.)

JAPPE: Also, you said in Venice that "Tram Stop" realized an early experience, without which you would never have become a sculptor.

BEUYS: Yes, that's the reason why I always wanted to realize it, and often made initial attempts to execute it, . . . this project that I've always carried around with me. Because I really would probably not have become a sculptor. I experienced, at this place, as a small boy, that one can express something tremendous with material, something quite decisive for the world. That's how I experienced it. Or, let's say, that the entire world depends on the constellation of a few chunks of material. On the constellation of where-something-stands, of the place, geographically speaking, of the how-things-relate-to-one-another, quite simply. Without any content coming into play-for example, I did not register then that there were ornaments on top, that there's a kind of dragon head on it, and so on. That didn't-! didn't even see all that. I saw only that there was an iron post, and there were iron elements, in various forms lying around sunk into the earth and peeking out; when I came from school, I regularly sat there, because there was a stop for changing trams there, and, to use current language, I let myself sink down into this – yes, into this state of being seen by the other things. I often sat there for hours, probably, absorbed in the situation, quite simply, entered into the situation. So, the experience that . . . one can make something with forms.

Something similar . . . that connected up again, another of these linking situations, in Cleves, shortly before I became a soldier. I was glancing through a few books which I had saved from the book-burning, which of course we had in our school-yard, all kinds of things by Thomas Mann, and who knows, by . . . Hanns Heinz Ewers, and a couple of art catalogs, I looked at them again, some I had already read, there were incidentally a couple of Dada magazines in the group, with drawings by . . . George Grosz . . . that actually didn't affect me, and by Klee, that didn't affect me, but there was an illustration of a torso by Lehmbruck. There again I experienced, but not so powerfully as earlier, that it's all a question of forms. That one can do something tremendous with form [art]. That was another bridge of a sort which led further, also to the later decision. (Conversely, the sculptures in Cleves and his art-classes both "slipped right by" him.

Although I still remember the film about Michelangelo, that I was tremendously fascinated by it. And the teacher, he fascinated me. And the entire situation. You must remember, I went to school at a time when, firstly, there was hardly any talk about art, and, if you did see some art, it was Nazi pictures hanging in the hallways, but above all it was rare to go into a dark room where there was a modern projectng device, let's call it. I recognized nothing in this film. I looked intensely at this, the whole thing struck me as one seething chaos. So I really . . . Michelangelo, among other things, is actually the initiator of the baroque style . . . that is, all these ground-up forms, I saw it all like a huge sausage machine, one big seething . . . .like a kind of cloud-filled sky. Clearly, at that age I was not able to put things into context.

JAPPE: But you said that the teacher fascinated you?

BEUYS: The teacher fascinated me. Because he said something on the topic whose tone I found tremendously kind, tremendously kind. There too, I listened only to the sound.

There is this experience, a kind of waking dream, which keeps recurring, for two whole years. An experience where . . . I'm sitting on the roof, on the ridge of a roof.And . . .I'm repeatedly being told by a figure, coming from outside, I don't know how to describe it today, well, naively put, one could describe it as a kind of an angel, which said to me over and over: you're the Prince of the Roof. So, quite simply, this sentence came to me stereotypically again and again, the moment when the meaning became clear to me that the roof is the head. That wasn't said, it came out of this hallucination or daydream, that happened while playing; I was still very small. Suddenly, boom, there it was, and I moved off to the side. Suddenly l couldn’t play any more, I focused on this situation. Usually I then left the playground, we used to play these great games, and ofen took the boat out too, anway I then moved off to the side. Afterwards I was, how to put it, quite groggy, and had to work through the whole experience for a long time . . .

So, that's also a key experience. (Pause.) I would have to read up again how I expressed it there, in that book. Penninus is in my expanded Joyce . . ."Beuys extends Ulysses by six additional chapters" – if one can speak of a main character that work, then it's this Penninus. And, although many figurative things are drawn there, he is represented entirely in the abstract as a kind of roof form upon which there lies a stone which is just on the point of crossing the crowning point to roll back down the other side, and it's right there up at the top. So there's this immersion into this kind of mythological depth of concepts. Becuse this Penninus too is decidedly a mountain god, and has connections to, let's say, forces in the head. Knowledge forces, thinking forces, and so on, that then enters into this context with the concept of "mainstream?' In which stress in laid on the necessity of working things through in thought, and not just, as I said, making art, doing science . . . I believe that that's where to find the core of key experience connected to the necessity of putting things into a theoretical relationship, which, in turns, looks like a world structure, since in our day it can no longer be mythology, but it must be a world structure which incorporates the invisible ends of being human. That is, everything one calls the transcendental, or can call the metaphysical,the suprasensual, that is whatever completes on a higher plane that, which, in the course of evolution and of western scientific development, had to be catapulted out of the concept of science in order, for example, to learn rational thinking or develop a concept of science which enables human beings to develop technology. (Pause.) This key experience came up again and again, for at least three years, until it became dear to me, as I said, not through explanation by this shadowy, impenetrable, or ghost-like being which, as I also said, came flying in, but rather I had to deduce it myself from the situation, like a resultant in physics. It was as if it was inherent in the problem: I will go on saying this, until you understand, until you grasp the inner meaning of the text, what it means to a Prince of the Roof. Let's put it that way.

JAPPE: And being a Prince of the Roof means to find a theoretical relationship . . .

BEUYS: Yes,but not so baldly, I'd say. It means, let's say, to think of the head's forces. After all, one must consider, that this was present as an experience at an age when one is not normally allowed to be concerned with the head, if one wants to develop in a healthy manner. (Laughs) I was five then, or four, [or six!, a time when one lives from quite simple vital forces, especially me.

JAPPE: Were you actually an only child?

BEUYS: Yes. Only child. That is, there was a previous birth, but he died. (Pause.) And there is a profusion of such key experiences, whch exist as. . .either day or night dreams, and which are very important to me. Above all, the day dreams and the phenomena which have guided me to this inner relationship, which I consider important. I must be quite clear: an inner relationship, which I myself, in the first instance, consider to be important; so I'm not turning up and saying it is important in a wholly objective way. But I am one hundred percent sure that it is possible to build something up out of this which is also objectively important. I want to be very cautious about saying whether I can do that or contribute to that building up. I do believe that I can contribute something. That this circle of a representation of world, life, political organization, right down to the nitty gritty details of culture, law, and economy should come into a closed system. When I say closed, l do not mean something shut off from everything outside, but something that is as resolved and coherent as a natural law, a natural relationship. That's an intention that is absolutely contrary to the concept of pluralism, which says the world is rich, the world is so diverse, everyone is different, so just be liberalistic, just be pluralistic, just go and run away from each other so that there is no chance of a unified movement amongst humans which can resolutely – here's the concept of the closed system again – and with a unified idea defend against oppression. In my opinion, all this is implied in these basic experiences.

JAPPE: Do you think that you were born with this structure, and did it become clear to you through certain experiences? Or did the experiences structure you? Do you know what I mean?

BEUYS: It would still be useful if you formulate it again, then maybe I can say some thing in response.

JAPPE: An experience like the Prince of the Roof . . . is that a message to someone already formed in such a way to receive this message? The old question – to what extent is an artist made by nature, to what extent by nurture; of course there are elements of both, but where is the emphasis?

BEUYS:. . . or let's say the following: I believe it is dependent on a person being born in a certain condition, for that person to recognize such things, which another person cannot assimilate because part of it doesn't reach him. When receptivity is not there because of hereditary disposition, then it is probably very difficult to get it in later years. In principle all human beings can be worked on in this way. I'll describe this process of being worked on as what happens when something spiritual comes to a human being, so that he is no longer just a natural being, like an animal, the postulate of not being divided can be fullfilled in the poorest hovel, and I mean this social reference not in the sense of class struggle [the concept of class) but in the sense of using as always in a stereotypical form, repeated over the course of an entire period. I am running across a meadow, in Cleves, an image, and there the train passes,travelling to Holland,to Cologne, Cologne-Neuss-Krefeld, then through the lower Rhine Kevelaar, Geldern, then comes through Cleves and goes on to Nijmegen. A completely empty meadow, with only the train on the horizon, actually not so faraway, but at that moment forming the horizon, as a line. The train stops, a man gets out, dressed completely in black,with a top hat on, approaches me and says,"I tried with my means, now you try with your means-alone!" (Laughs) That was all.

JAPPE: How old were you?

BEUYS: Oh, about seven or so, perhaps a little older.

JAPPE: What's meant by the word "means"?

BEUYS: I can't be certain of that. He might have said, "in your way." I think he said: "means." That's how it often is with this kind of experience, whenever the man speaks, or anyone speaks, then he's not really speaking, one shouldn't interpret that only in the acoustic sense. It comes across as information; that is, the image makes no noise. But one understands what the man is saying; it comes across directly as a thought. Everything takes place without sound. But he moves his mouth and one understands what he is saying.

After my time as a prisoner of war, when I was 28, when others had already fully dealt with their development, I began to study. No power in the world forced me into science. Or into art. Not my teachers. Or my parents. My parents would have preferred to see me – and here's something purely superficial – going to the lard factory in Cleves. Because we have in Cleves one of the largest factories for butter, margarine, and lard.

JAPPE: What did your parents do?

BEUYS: My father dealt in agricultural products. Whatever one needs on a farm: artificial fertilizer, corn, milling flour too, at home we roughground it, when it was flour for baking purposes, then it was transported to Neuss, Wehrhahn or to . . . Gottschalk, Düsseldorf, or what's he called, the other one . . . Plange, August Plange. I know them all, these mills in Düsseldorf, as a child I always came along. When there were big transports, mostly affter the harvest, once or twice a year, there was always a trip to the big mills.

JAPPE: And why should you have worked in a lard factory?

BEUYS: Because it was the most comfortable way to get a good job. (Laughs.)

JAPPE: Did you gain time for your development because of the war or was it a postponement for you?

BEUYS: I certainly don't regard it as lost time. I could have had those experiences nowhere else, that's for sure. For a concept of work that is after all oriented towards experiences, it was more a benefit (Pause.) And the categories of experience were so densely packed, that one could never speak of boredom. From the training period, when one is not left in peace for a second, when there was always something happening, always something happening, right up to the whole situation on the front, . . . during operations, or afterwards in a prisoner-of-war camp . . .

JAPPE: Yes, but after your studies you spent another ten years in seclusion, in the countryside, unlike artists today, who start exhibiting at that point.

BEUYS: I had no need to take part in the modern art world. (Beuys notes that even during his studies, he had earned money through commissions and competitions.) And therefore I always had enough money, I had no reason to complain, I could rent the studio in Heerdt and worked there independently. When I graduated from the Academy, I had more of a need to move to Cleves. And I did my most important work in Cleves. Not at the Academy. Everything that's interesting about my drawings, for example, didn't arise at the Academy, but in Cleves. I destroyed 99% of everthing I did at the Academy, because it had only training value for me. That was true with my work for Matare, too; I saved nothing, with only a very few exceptions, where there are still a few samples of works. Nothing of the study drawings either, at most there are l0 or 20 nudes, portraits.

JAPPE: Why did you then decide to undertake the actions?

BEUYS: (Pause.) I don't believe that I decided to undertake the actions. Rather I believe that the actions developed quite organically from the intention that this thing with art must be expanded. The first possibility of course, was to approach it interdisciplinary. Even before the actions I had repeatedly given thought to the fact that one unthinkingly used the terms sculpture as carving and sculpture as forming interchangeably. With this intention I was also interested in incorporating sound, and the opportunity presented itself through this contact with musicians, like Paik and others,with whom I had good contacts from the begining. But at a certain point actions stopped being extended, and that’s surely the reason why today actions, happenings, fluxus are nothing more than a certain style within the modern art scene. I think that the theory inherent in the topic wasn't grasped. That the concept of action should not be restricted to a physical action within the art world. But rather that one must see it as a political action, and also must generalize the concept of action.

JAPPE: Yes, but that's what you did.

BEUYS: Yes, I did, but those in the movement . . . most of them didn't do it. Most of them didn't move beyond neo-dada. I always had disagreements with those who wanted to apply the term "neo-dada" to these activities. Then it did in fact not go beyond that. (Pause.) Meanwhile, I do not diferentiate between an action with classic objects or an action without or a lecture or a pure theory. No difference applies. Because the action characteristic really does now, one could almost say, occupy one point in the information system; in terms of information theory, it should be considered no different from a general truth, i.e from a fact where no artist has the right to extract anything for – or herself, as if it was something special.

It is simply impossible for human beings to bring their creative intention into the world any way other than through action. And only this perspective justifies the thesis that everyone is an artist, which, put like that, is a provocation, because in reality and qualitatively, not everyone is. But potentially they are; so we could say that from a purely anthropological point of view, the concept is correct. I believe. And this is precisely where the question of freedom comes in – and that is definitely now an explosive political arena – to what extent can a human being today be a freely creative?

September 27, 1976