Blow-Up: From the Word to the Image: John Freccero

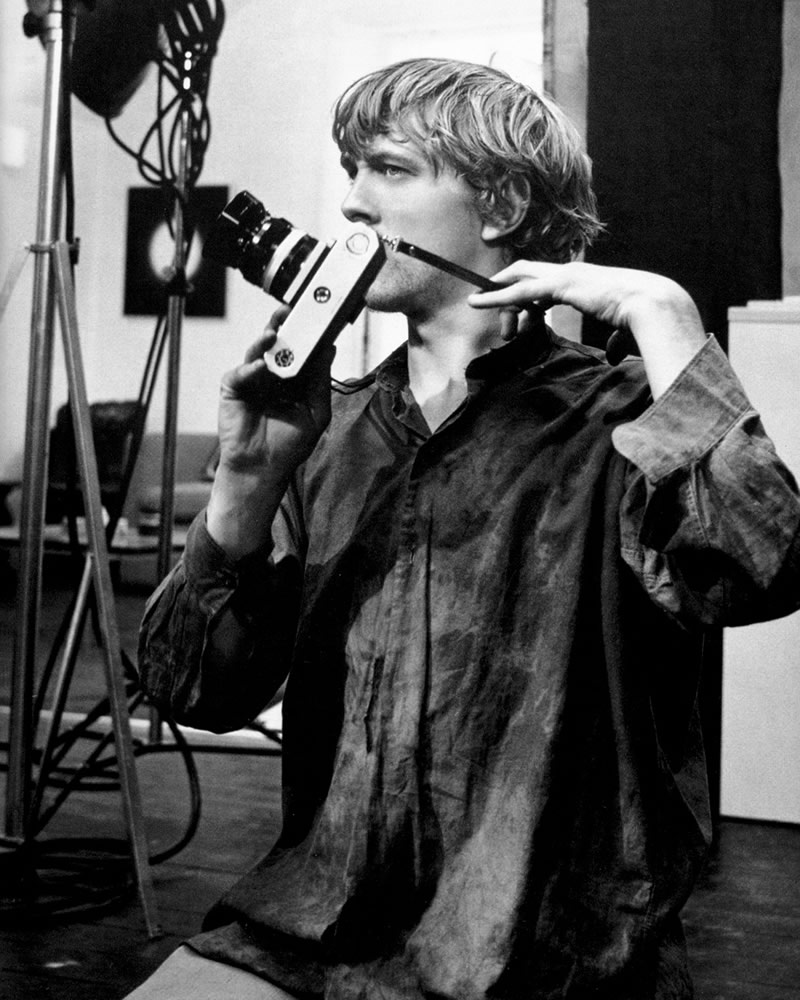

Blow-Up: David Hemmings 1966

In the vocabulary of the communication arts, the word “linear" has come to have a pejorative meaning, standing for a mode of expression, indeed for an entire culture which seems to have been superseded. Linearity and sequence have given way to graphic totality, the written word to audio-visual communication and literature itself, long since displaced as the medium of popular escapism, sees its survival threatened even among the intellectual elite. The current popularizers of the cultural revolution are of course the McLuhanites, but the attack of film estheticians took place much earlier and was both more subtle and more sustained. The burden of their critique was that literature, far from enriching the new visual medium, was in fact a contamination.

Recently, the argument seems to have become more embittered by having been ignored for to long by the academy. Andrew Sarris, for instance, writing in the New York Times, noted petulantly that the literary establishment has at long last discovered the film, is trying desperately to claim it as its own, but that such efforts are futile: "No serious scholar of the film is no concerned with the sudden conversion of the litterateurs." The implication seems to be that the superannuated students of literature had best stick to their obsolete discipline and make way for the cultural revolution.

In part, of course, the anti-literary polemic has been sustained by the vagueness of its terms. Sometimes the word "literary" seems to refer to narrative cliches or to the official culture traditionally charged with embalming them. At other times, words themselves seem to be under attack and 'literature'. is taken to mean the verbal medium in general.

For all the confusion, however, the tone is both too shrill not to betray a certain anxiety among film estheticians about the nature of their own medium. It is traditional to point out that the film is distinct from, say, both the novel and the theatre in that it is a visual, often representational medium (unlike written literature), but with a technically mediated, constantly shifting and completely controlled perspective. At the same time, it is equally obvious that the film is a system of communication that functions, even when it is totally silent, very much like language itself. As early as Sergei Eisenstein and a generation or so before the advent of semiotics, it was recognized that selection and combination, the twin characteristics of the linguistic act, were analogous to Eisenstein’s description of the process of montage, or editing, while the double articulation of language is already implicit in his distinction between photographic representation, comparable to the phoneme, and the image, the result of an interpretation and therefore comparable to a unit of meaning. When Eisenstein illustrated his principles of montage with a translation of some verses of Pushkin into a hypothetical silent "shooting script." he effectively demonstrated certain undeniable affinities between literature, understood both poetically and linguistically, and the new art form which he helped to create.

My purpose in outlining some of these elements of the debate about literature and film is not to enter that debate directly, but rather to introduce my subject. Michelangelo Antonioni, whose work seems to be surrounded by precisely the same controversy. While Antonioni has been popularly upbraided for his incomprehensibility and dullness, what one wag has referred to as "antoniennui," several film experts have accused him of what seems to be an opposite fault: that is, of being too literary and too pat.

One Italian critic goes so far as to denounce his "literary corruption," thus adding the moral indignation of the film theorist to that of the censors and assuring a succes de scandale in the sophisticated periodicals as well as at the box-office. So an evaluation of an Antonioni film inevitably rehashes the traditional polemic and revives the old confusions. with partisans defending the stark visual virtuosity and detractors pointing to the literary sentimentality of the creative genius whose work seems as problematic as the principles of the medium in which he works.

The quality of Antonionion’s films was a subject of heated debate long before the appearance of Blow-Up, the film which both intensified the debate and shifted it to a more popular forum. All the critics agreed that the film marked a radical departure from Antonionion’s previous idiom, both visually and thematically. For one thing, Monica Vitti was missing. For another, swinging London seemed to lend more visual movement to this film than to any of his others. Finally. perhaps most startling, this film seemed to have a plot, or almost, and the first half of it prompted some to speak of it as though it were alienated Hitchcock. Put most simply, while nothing ever seemed to happen in L'Avventura, La Notte, L'Eclisse, or II Deserto Rosso, here at last something had indeed happened, although it was difficult to say with any assurance what it was. For the film theorist, the radical change in subject matter marked a thematic change of great importance. Because the leading character is a photographer who attempts to interpret his own work, it appeared that the director had left off his exploration of neurosis and alienation in order to make his own entry, however oblique, into the debate about the nature of his own medium.

Blow-Up is in fact a series of photographs about a series of photographs and so constitutes what might be called a metalinguistic metaphor, a highly self-conscious and self-reflexive meditation on its own process. Because it is a discourse about discourse, it is subject to all the charges of ambiguity that are usually levelled at such self-contained messages, even when they occur in everyday speech. At the same time, however, that ambiguity places it within a literary tradition, founded perhaps by Petrarch, in which literature's subject is itself and the portrait of the artist is his act.

There can be no doubt that Antonioni's mod photographer, Thomas, is in fact an artist—primarily a visual artist. Early in the film, a scene at the house of his painter friend establishes a symbolic equation between their respective techniques. Bill is contemplating one of the paintings that differs markedly from all his other work in that it contains a figurative element, or what seems to be one:

While I'm doing them, they don't say anything to me—just one big rness. After a while I find something to hang onto. Like that leg there. Then it comes through by itself. It's like finding the key in a mystery story.

For those who fail to recall those lines when the photographer examines his own work, Antonioni has Patricia, the painter's companion, restate the equation when she sees the photographic blow-up: “It looks just like one of Bill's paintings." When he is first introduced, Bill would seem to be the photographer's antitype, a loser trying desperately to keep his painting, which Thomas jocularly threatens to steal, and his woman, who wants desperately to be stolen. By the film's ending, it becomes evident that the parallel is exact, for Thomas too has lost both his work of art, which is stolen, and the woman he coveted who is somehow responsible for in loss.

As a visual artist, however, Thomas differs markedly from the painter and even from his fellow photographers in that he aspires to totality. He seeks to transcend time and to achieve the self-containment and the autonomy of a world created by his camera rather than illustrated by it. This, I take it, is the sense of a detail which most critics of the film have overlooked but which seems to me essential. One of the first things we learn about Thomas and the reason why he finds himself in the park, at the scene of the crime where he makes his discovery, is that he is putting together, structuring, a book of photographs. Thomas differs from his photographer colleagues, whose craft is documentary, in that his gaze transforms the representation of reality into its image, an interpretive act resembling that of the painter. He differs from the painter, however, in that he introduces the temporality of syntax into his art, juxtaposing images into a structure along a syntagmatic axis, which is the essence of language or, for that matter, of montage. Had he succeeded in putting together his book of images and achieving a real simulacrum of time. he would have come very close to resembling the film maker who has been accused of excessively literary preoccupation.

However veiled the allegory and however arch the transposition, the confessional suggestiveness of the story is the unmistakable consequence of the metalinguistic metaphor. As long as one remains within a narrative structure, then the story that tells its own story is perfectly self-contained. When stories are great art, however, and not myth, they come into existence through a consciousness that exists as story-teller: to tell the story of how the story came into existence is necessarily to portray the story-teller, no matter how metaphorically, just as the story-teller's autobiography, as story-teller, is the story he tells. So with Antonioni's meditation on his own art: Thomas is perhaps the portrait of the director as a young director and his failure is Antonioni's subsequent triumph.

The structure is familiar in literature, from Dante to Proust, and recently introduced into the film by Federico Fellini, the title of whose cinematic autobiography, 8 1/2, points unmistakably to the fact that it is a retrospective attempt to understand his own work. The story is of a director who, while fearing that he is washed up after what seems to him to have been a fragmentary career, nevertheless is filming a film that is in fact the film we view. Most interesting from our standpoint, however, is the conclusion of 8 1/2, where the director is called among to sum it all up, both as character and as director, and to give significance to all that went before. Finding himself unable finally to do this, he crawls under the banquet table where he is being honored and shoots himself, whereupon he is immediately resurrected in time to conduct his band of mimes and pagliacci in the parade that is Fellini's trademark, the Trionfo, so to speak, of illusion over reality.

Fellini the magus hides his human despair, just as do his characters, behind the mask of the lie; in this case, the phony suicide, which both gives a conclusiveness to his life story and grants him, author and persona, the leisure and the Archimedean point outside of time from which to tell it. It is this compromise with authenticity, the willing embrace of the lie inherent in the medium itself, that Antonioni has always refused. Fellini perhaps set up the problematic, the cinematic code, and Antonioni perhaps assumes it, for film makers, no less than writers, must work within a tradition; nevertheless, the bittersweet of Fellini's lie is rejected and the code is assumed only to be destroyed. In its preface to a collection of six screen plays, Antonioni had written: "The greatest danger for the film maker consists in the extraordinary means the medium provides in order to lie.” Blow-Up is the dramatic refutation of Fellini's make-believe and its bleakness consists in the fact that the only alternatives it offers to the lie are the search or silence.

To make the point about the metaphoric relationship between the director and his protagonist a little more convincingly, I should like for a moment to go outside the "text.” In an interview on Italian television, Antonioni was asked why, when he knew it would cost him ecclesitical approval in Italy, he included in the film the photographer’s orgy with a pair of teenyboppers. He replied that while he was not at all averse to incurring the displeasure of the censors, he really had something else in mind. In a world as notoriously alienated and neurotic as his own, he felt the need to provide some relief with an episode of good clean fun. The television interviewer was an ideal straight-man, since he had not seen the film and therefore could not catch the irony. Even the most casual viewing of the film would have revealed that it is precisely for the same reason, to find some erotic relief from a gloomy world, that Thomas goes into the park in the first place. His book of photographs includes a series of portraits of derelict old men in a public dormitory, most of them more or less close to death. In order to relieve the grimness of his photographs, which he senses with some detachment, he goes into an Arcadian scene, a park with an enclosed garden, where he photographs a pair of lovers. It is only later that he discovers, with the retrospective gate of the artist interpreting his own work, that he has in fact portrayed not the embrace of lovers, but the death of an older man. In short, the fact of death which he had been seeking to evade. Had he seen Poussin or mad Panofsky, he would have known that this disillusionment awaits all attempts at pastoral evasion: "Et in Arcadia ego." Death resides even in Arcady.

What makes the photographer symbolically capable of making that discovery is of course a discovery about himself. The interpretative act of the artist does not depend so much on the physical evidence as on the construct which one is ready to bring to it and before Thomas can understand, his own authenticity must be questioned. This occurs in his orgy with the aspiring models, who stand chronologically in relationship to him as does the girl, Vanessa Redgrave, to the older man for whose death she is somehow responsible. By a cinematic tour de force, Antonioni presents us with the visual equivalent of one of the oldest double-entendre of erotic poetry: to die, the orgasm as the moment of death. Lying prostrate on the floor of his studio after his debauch, the photographer looks up and discovers, or thinks that he discovers, the erstwhile older lover lying in the photograph in precisely the same position. He does not as yet suspect what the audience has already grasped: just as Thomas is the metaphoric embodiment of Antonioni’s art, so the older man is the metaphoric embodiment of Thomas' art. The dead man is the dead-end conclusion of Thomas' book and thus, symbolically, an all too definitive portrait of the artist which cannot be revived by cinematographic sleight-of-hand.

The photograph of lovers in the park was to be not only pastoral relief in Thomas' book, but its very conclusion. When they meet in a restaurant to discuss the photographs, Ron, the photographer's friend and publisher, asks him which of the photographs of the older men he would like to put last. Thomas, who does not as yet suspect what his films contain, replies:

None of these. I have something fabulous to wind up with. In a park. I took them this morning. Let you have them tonight. There's a silence in them a peace... The rest of the book is violent enough and maybe it would be better to end it this way...

It is this sense of the ending, of poetic closure, that marks Thomas as a literary man, an expert in montage, like a formalist literary critic who wishes to achieve a balance and a symmetry in his interpretation. The subsequent discovery, that of the death in the park, takes him far beyond formalism, however. If the aspiration of the artist is to express himself in a formal structure, with an ending that is both neat and authentic what in his life can possibly correspond to finality in montage, unless it is death?

The silence that ends his adventure in the park is like the syntactic silence of Merleau-Ponty or, before him, of St. Augustine, who first established the parallel between the unfolding of the sentence and the progress of the soul. For Augustine, the eternity of the Platonists was the world of pure form, too abstracted and remote to be of existential concern to men. The time of the flesh, on the other hand, was the chaos of unintelligibility, a tale told by an idiot, signifying nothing. Between these extremes there stands the word, as the Word of God stands between eternity and time, syntax as time redeemed and pressed into the service of significance. As the phoneme derives meaning retrospectively with unfolding sound, on too do the words and the entire sentance and the discourse as a whole, whose significance falls into place only at its conclusion. Insofar as language is not extrinsic to man but part of his very nature, so the linearity of syntax is an emblem of human time and death gives meaning retrospectively to life. Under such circumstances, it is difficult to see how anyone would even attempt autobiography. Life can of course be the metaphor for the book, just as the book can be the metaphor for life; even writers seem to be interested in both. The point is that the dual finality in a single literary structure is inconceivable. It is perhaps for this reason that Jean Paul Sartre's autobiography, Les Mots is deliberately open-ended. Short of an Augustinian spiritual death and resurrection, the syntactic silence that follows life precludes sharing the significance with others.

The same is perhaps true of the cinematic genre founded by Fellini. Insofar as it pretends to capture autobiography within a complete structure—.and films must be complete—it is doomed to failure for the same reason that makes it impossible to take inventory before the store is closed to business. If we object that this does not apply to spiritual autobiography by the novelist or film maker, whose metaphoric biography is simply his definitive statement about his own art, then the problem is attenuated, but no less absurd: the artist can make no definitive statement about his art until he ceases to be an artist, which excludes his definitive statement from its own corpus. It is in this sense that the logical absurdity of the definitive book matches the logical absurdity of definitive autobiography. There seem to be only two ways out of this dilemma: either to deny any point of tangency between illusion and reality and embrace the lie with full creative awareness, as does Fellini, or to dramatize the dilemma with a surrogate in search of a conclusion, a film about its own impossibility, like the dead body which Thomas no sooner touches than it disappears. Antonioni, like Marx, insists that truth resides not simply in the goal, but in the process whereby one approaches it, even if it is never attained. He writes: "A director does nothing more than search for himself in his films. The films are not the record of a completed thought, but rather that very thought in the making."

This is the Antonionian search which finds visual incarnation in so many of his films, where nothing happens and perhaps nothing ever will happen. What happens in Blow-Up, however, happens to an artist who, by the film's ending, has ceased to exist except as Antonioni's counterstatement. The technical process of the blow-up is obviously the metaphor of the search, no longer dramatised in exterior terms as a neurotic odyssey, but as an experience that the Middle Ages would have called the journey intra nos. Antonioni had long been fascinated by the metaphor. Three years before the appearance of the film he had used it as an example of the search for the truth in the image. After describing the process in technical detail, he glosses its significance: "We know that beneath the revealed image there is another, more faithful to reality, and beneath this still another, and once more another. Up to the one image of reality itself, absolute, mysterious. which no one will ever see. Or perhaps up to the decomposition of any image at all, of any reality at all. In this sense, even abstract cinema would find its own raison d'etre." This perhaps makes it clear that Antonioni intended his photographer to achieve his most creative moment not behind his lens, but at the enlarger. After Thomas' suspicions about the lovers' tryst are aroused, he begins to examine details of the prints arranged in sequence around his walls, first with a magnifying glass and then by successively blowing up one of the details to the point where it seems to be nothing but a series of black and white blotches. At that moment he sees, or he thinks he sees, the man being manoeuvred into position for an assassin's bullet from behind a hedge. The interpretation would have been impossible without the interpretive context, which casts the photographer in his self-conceived heroic role and prepares the audience for a mystery story conclusion. Thereafter, both are disappointed, the photographer to discover he did not actually prevent a crime and the audience to discover that it is the body, the reality, which is the object of the search and not whodunit.

Antonioni’s, rejection of Fellini's joyful prestidigitation is on both 'metaphysical and sociological grounds, an indictment not only of a cinematic technique but of the whole world of graphic inauthenticity. Thomas lives in a world of which he is king and, virtually, creator. Models are puppets in his hand which, like Hoffman's dolls, come to life only at his command. He tells them to shut their eyes and so they remain while he seeks some distraction. The image is power in swinging London and he is the image maker, mistaking the synchronic, graphic cut through reality that is his own creation for his very life.

The public consequence of this private presumption is his role, not as king of the image, but as peddler. The sub-plot involving the antique shop, which the photographer wants to buy, portrays him as something of a pusher of evasion. The bric-a-brac of another time is a store house of used images waiting to be rearranged by the skillful bricolage of the photographer into marketable images, camp, for the new campy inhabitants of the decaying neighborhood. The old man who runs the store, a custodian of the past, refuses to sell him anything, but the young girl, who is presumably inheriting it, as the young always do, will sell him anything, just to get away:

I want to try something else. Go away. I'm sick of antiques.

Go where?

To Nepal.

Nepal is full of antiques!

Then maybe Morocco would be better.

When the photographer finally buys something from her, it is an old airplane propeller, a symbol of flight, but he wishes to hang it in his studio as a fitting emblem of the place where magic-carpets are put together in the twentieth century.

The photographer's arrogance reaches its height, however, when he concludes in his dark room that his presence in the park actually prevented the crime from taking place. After the visit of Vanessa Redgrave, he discovers the killer and calls his friend Ron to announce: "Listen, I saved a man's life!” Before Thomas can describe in detail what happened, however, he is interrupted by the arrival of the two teenagers who, in spite of their youth, or perhaps because of it, are the occasion for the photographer's discovery of the dead body.

According to our mythology, it was after the fall in the garden of Eden, that sexuality first entered the world and with it entered death. According to the Church Fathers, the act whereby a man asserted his manhood was the same act whereby he entered the cycle of generation and corruption that indicated, unmistakably, how transient his life would be, how soon he would have to make way on the generational line for his own children and those of others. For various reasons, we no longer perceive the connection between sexuality and death with the same immediacy that critics tell us our literary ancestors felt; and we are unaware, perhaps, in indirect proportion to our age. Thomas is twenty-five. so that his absolutely indiscriminate sexuality is what one might expect both of a young man who thinks he will live forever and of an artist who has as yet felt no limitation on what he takes to be the transcendence of his art. The fact that the film is absorbed with his coming of age, however, indicates that his creator is middle-aged. The photographer's prise de conscience, both as artist and man, comes about by a kind of triangulation or bracketing, where coordinates are determined visually by splitting the difference between a point that clearly falls short and a point that clearly exceeds the target. He emerges from the category of youth when, after making love to teenagers. he remarks to Vanessa Redgrave: "Your boy-friend is a little past it, isn't he?" His intention is obviously to suggest that, in point of age, he would be an ideal companion for her. For the first time in the film, Thomas assumes an identity that is not just his artistic transcendence, but rather that locates him exactly on a time line with all other mortals and this one in particular. When he first saw her in the garden he was fascinated. There, as in so many literary gardens of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Narcissus discovers an image of himself and thinks he has fallen in love.

Vanessa Redgrave is the first woman whom the photographer seems genuinely to desire and whom he treats, almost, as another human being. Until her appearance in the film, Thomas' sexuality seems as dehumanized as his art, the sexuality of the voyeur (a metaphor for novelistic detachment at least as old as Chaucer), who to transcends his own mortality that he can achieve satisfaction merely by observing, like some God, from a privileged perspective. So he makes love to the model Verushka with his camera or, alternately, frolics with the little girls wrapped in the purple paper he uses for his back-drop. So too, he looks at the pleading eyes of Patricia while she somewhat distractedly allows Bill to make love to her. This last scene is virtually a literary topos: in Chaucer 's Troilus and Creseyde, when the loving couple are finally in bed together, Pandarus keeps them company while he retires to the fireside to read his old romance. Here, while Patricia and Bill are making love, Thomas turns to look once more at Bill's nearly figurative painting to see what it reveals. The technology may differ somewhat, but the mechanism is the same.

With Vanessa Redgrave, on the other hand, he finds a kindred spirit whose identity and past are as mysterious as his own. Antonioni under-scores their complementarity even by their dress, for in the scene that provided the publicity stills, the whiteness of her bare flesh and her blue skirt are the colors, symmetrically reversed, in which he is dressed —blue shirt and white slacks—while both she and Thomas are wearing identical belts. As they stand in the doorway of the bedroom, the scene seems to be set for what might have been the only completely human encounter of the film, but they are interrupted in a moment that, in another cinematic atmosphere, might have provided comic relief—the delivery of the propeller which Thomas had purchased at the antique store. The almost funny moment marks the intrusion of Thomas' vocation and the evasion of reality that it represents. By the parallelism that the film has established between the artist's sexuality and his art, the failure of human love, or at least human contact is exactly equivalent to the failure of his work to achieve humanity.

The meeting with Vanessa Redgrave proves to be an amorous disillusion, so that once she disappears from the studio, she no longer has any part to play in the film. After Thomas' discovery that the story was not quite as he had envisioned it, the audience discovers that the plot of the film is not the suspense story it had been led to expect. The object of Thomas search is not the killers or the perpetrators of the plot, but the body itself, the authenticity of which he had caught a glimpse in the park. The search is a familiar one in the artistic work of which Thomas is the metaphor, the search of the heroine in L'Avventura, the spiritual odyssey of II Grido, but in this film, the truth of Antonioni's revelation is briefly revealed in the moment when the photographer touches the body, as if to feel the point of tangency between reality and his art. Antonioni's sociological indictment finds expression again in the photographer's frantic search for some solidarity in order to sustain him in his investigation. As the revelation had been achieved by a kind of bracketing, so he turns to society in the same order, first to the young, who are drugged joylessly by their music, and then to the older, drugged by their cocktails and marijuana. In each of these episodes. the photographer is momentarily taken in by the collective, conditioned desires of the society around him and each time, rediscovering himself as alone in his knowledge, he moves away from his surroundings in despair and disgust. The guitar, smashed by the musician, becomes valorized by the frenzy of his young fans and the photographer joins in the struggle to possess it. Once free of the mob, he throws the worthless bits away. Like the airplane propeller, the intrinsic worth of the object is nil, but it is given value by the colletive desire imposed on the crowd by image peddlers. This analysis of London night life, which dismayed English audiences, is the image of world possessed by a kind of madness that seems to blind it to the fundamental fact of death, in one as in life. The demons of this evasion inhabit the entire world of mass media, they are its spirits, and so they begin and end Antonioni’s film.

The film opens at dawn with a group of students, extravagantly dressed, presumably for Rag Week, their faces painted white, who descend from their jeep and scatter to inhabit the whole of the city. Like the Untorelli of Manzoni's Promessi Sposi, their mission seems to be to spread the plague whose name is perhaps best established by the strange protest sign GO AWAY, that one of them gives to the photographer as he speeds away from the desolation of the public dormitory. The same students close the film in the famous and problematic ending, again at dawn, where some watch and others play a phantom tennis match without a ball. Thomas watches the students, at first with amusement, as they follow with dead seriousness and the some joyless and empty look that he had previously seen at the rock session, the flight of an imaginary ball. When the phantom ball seems to have gone outside the court, presumably at his feet, they plead with him with their eyes to return it. He hesitates, finally stoops as if to pick something up, weighs it in his hand and finally throws it back, thus collaborating in their phantom game. As he walks slowly away, the sound of a tennis ball against a racket can clearly be heard, and the camera moves slowly away from the minute figure of the photographer until he quite literally disappears before our eyes.

The demonic character of the students can scarcely be doubted. Their fantastic dress, their appearance at dawn, their white faces, their station in life and weird behavior mark them clearly as what anthropologists would call "marginal" figures, the demons of tradition. who mediate between the world of the spirit and the world of matter. Their appearance in the stark world of Antonioni's film is inexplicable until one realizes that they are not meant to appear in his kind of film at all. They are Fellini characters, the clowns and fantastically attired circus people, whose joy is gone and whose magical illusion is unmasked as the lie that Antonioni takes it to be. Thomas' collaboration is the sign that he has joined the ranks of the talented perpetrators of illusion, and that he disappears both as person and artist, leaving Antonioni to his lonely search for the truth.

I remarked at the beginning of this paper that literature seems to have been superseded in both the popular and the intellectual imagination by the new visual media. But Antonioni's film makes the point that the recognition in art of human mortality can be evaded but never superseded. His critique of the medium and of its capacity to lie, at the very inception of a new technological era, is reminiscent of the critique of the new printing medium launched by Cervantes at the beginning of this (now dying) linear age. In the second part of Don Quixote, Altisidora has a dream which symbolizes the disenchanted view of the new cultural revolution. She describes her dream:

The truth is, I arrived at the gate of Hell, where something like a dozen devils were playing tennis, all in their breeches and doublets, with their collars trimmed with Flanders lace and with ruffles of the same which served them as cuffs with four inches of new bare to make their hands look longer. They were holding rackets of fire and what most astonished me was that instead of balls they used what looked like books, stuffed with wind and fluff...

Technology has been refined to the point that the message has lost even the physical reality still represented by the book, the word has turned to image, while sender and receiver stare blankly as though their transaction at some point still touched the solidarity of the ground. Their game. in which everyone loses, is one that Antonioni refuses steadfastly to play. In his own terms, he can hope for no greater victory.