Cool Times

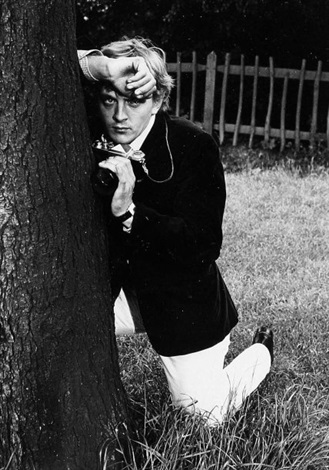

David Hemmings 1966

The young celebrity-hero of Blow-Up, a film concerned with, among other things, the pandering to celebrity and consequent chic freakiness of London in the sixties, is played by David Hemmings, himself an actor who made it in the sixties mainly through playing represemtative youth roles. And Hemmings' function in the film is indeed to behave more as a representative type than to act as a discrete person. This follows, in part, from Amonioni's developing interest, most in form in his two latest films. Blow-Up and Zabriskie Point, in de-mythicizing the concept of personality (that is, of personality considered in its usual meaning of a fixed identity or pristine "individuality"). The star fashion photographer portrayed by Hemmings remains the most anonymous and protean of Antonioni's protagonists (as well as, it should be noted from the start, the most successful: he is neither a professional man "blocked" in his work and career like most of the male leads, nor, like the lead of II Grido, a suicide). The abstract characterization also lends itself to a focus on the same ideas posed by Julio Cortizar in the short story that provided the film's title and point of departure: the problematic equation between an author and his hero, between a narrative and its embodying voice. Cortizar begins his story:

lt’ll never be known how this has to be told. in the first person or in the second, using the third person plural or continually inventing modes…[1]

Yet, ". .. one of us all has to write, if this is going to be told." As the story builds, with Cortizar (in his own voice) taking turns in the

telling with his narrator hero Michel, indecisiveness about an establishing point of view becomes precisely the point. Michel's own point of view is defined—and criticized—by the other voice as being too literary:

Michel is guilty of making literature, of indulging in fabricated unrealities. Nothing pleases him more than to imagine exceptions to the rule, individuals outside the species, not-always-repugnant monsters.[2]

Here, being literary is equated with being romantic. Throughout the story, the other narrator interrupts to qualify or to confuse Michel's more romantic interpretations of the relationship of a middle-aged woman, a youth, and a third person seemingly waiting at a distance—all beheld in a park. Nor are the shifting planes of narration merged into a single unity of perspective or slant, rather, they take form only as a mosaic of interpretive possibilities.

Antonioni shares Cortazar’s dry, relentlessly quizzical manner. Like Cortazar, he discourages in his audience any simple identification with his lead figures; even as he discourages our impulse to define his own attitudes and characteristics as those of his characters. Blow-Up centainly does not present a hero quickly identified with; yet in line with the approach in Cortizar's story, in none of Antonioni's films is there a more open play on the relationship between an auteur and his persona; and in none are certain equations between the sensibility of the creator and his creature more manifest.

In the story, Michel is an amateur photographer living in Paris; Thomas, his counterpart in the film, is a professional photographer living in London. The generation consciousness of the film, however, matters far more than the geographical change; indeed, Blow-Up falls into the current cycle of youth films through its categorical emphasis on its hero's youth—an emphasis absent from the story (as are most of the incidents of the film, including the culminating one at the tennis court).

The transforming of its young protagonist into a youth-figure, then, becomes a main departure horn the story. By reason of his age alone. Thomas is granted the prerogative of enjoying a freedom from the neuroses that weigh down those heroes of other films who belong to an earlier generation: by itself. this freedom would serve to bring him closer to the awareness of the film-maker for whom the very process of delineating the psychological blocks and dilemmas of the characters of such films as La Notte or L'Avventura would seem to have been the means of moving beyond them. And, unlike the unidimensional young stockbroker played by Alain Delon in L'Eclisse, Hemmings' scene is one of art and fashion. In his kind of work, therefore, he comes closest to Antonioni's own metier than do any other of Antonioni's main characters. This introduces a third level of interest—in addition to those of youth-figure and authorial voice—in the presentation of the hero; for, in his presentation, we also find various hints of that old warhorse—and key mythological hero of Antonioni's own generation—the artist-figure. All of which brings us quite a long way from Cortazar's story. Again, in contrast to the story, the action of the film leads to a merging of viewpoints and consequent difference in thematic development in the final tennis court sequence—the tennis court itself reminding one, on the biographical level. of Antonioni's own youthful times as a tournament-winning tennis player. In sum, the progress of the Hemmings character through Chelsea-Knights-bridge-Hampstead embodies the related themes of youth and art.

Throughout the film, the focus is on Hemmings: what he represents in the terms suggested—marks the key interest and is reinforced through the relative lack of documentary or atmospheric emphasis on London itself. The camera never pauses long enough to allow us to enjoy a shot of an historical site or other familiar locale. Unlike the quick Cook's tour along King's Road, for example, which Joseph Losey offers us in the opening shots of The Servant, Antonioni hardly gives us time to get our bearings. Nor does he present his characters as distinctively "British types" seen from a special or foreign point of view—no more than the characters of Zabriskie Point interest him as national types (a point lost on the film's numerous critics on this side of the Atlantic who bemoaned the unreality of its lead figures as—what Antonioni obviously was not, after all, aiming at—hippies on the all-American model).

II

We first see Hemmings stalking and "shooting" vagrants and other derelict figures of the streets; he has been commissioned to compile a series of photographic studies of such figures to be included in an expensively planned picture book on London, with special attention paid to its lower depths. The pictures must also serve to bring the volume to an upbeat close; so Hemmings is on the lookout too for people in poses suggest of—in his editor's words—''peace and harmony," rather than outrage and violation. What better than shots of a couple strolling in a park seemingly on a lovers' amble? When developed and blown up, however, this last set of shots reveals that, what from his distance had appeared to be spontaneously playful and cajoling gestures on the part of the woman (Vanessa Redgrave) in the picture, had more likely been a series of calculated manoeuvres culminating in that ultimate violation: murder. In a corner of one of the blow-ups is what looks like the body of her victim, hunched nervelessly on the ground in a pose similar to that of the derelicts hunched over in the street and “shot," by Hemmings earlier in the day.

"Peace. is precisely what is nowhere evident on our hero's rounds. When, in concern over the matter of his blow-ups, he seeks the editor of his book, the latter is shown finding his peace in pot; in his cloud of smoke, he remains impenetrable to Hemmings' queries. In a subsequent scene, when the woman in the park traces the photographer to his studio to plead for the return of the possibly incriminating photographs, she says in reaction to his sharp refusal: "You wouldn't act like this if these were times of peace!" To which he replies at once: "It's not my fault that there is no peace." She then offers to bed down with him as a means of getting her way, their exchange maintaining its curious equilibrium as, in the ensuing silence, he matches her sudden removal of her blouse by removing his shirt. An interruption at his door, however, draws him away, leaving the woman enough time to grab the pictures and run off.

The impromptu and abortive nature of this encounter is typical of all the other relationships depicted, whether personal or professional; it would seem to be typical of a time without peace. And the cool manner of all the characters—their manner is both unflappable and abrupt, both candid and aloof—is part of a style that clearly marks an adaptation to the jolting discontinuities of their experience. The discontinuous, unharmonious pace of things is also reflected in the varying degrees and kinds of sexual involvements pictured—none of which, to put it mildly, is on an idyllic plane.

The first of such scenes is that of the artist posing and photographing his model. As the phallic muzzle of his camera nudges toward the girl, who lies prone before it, Hemmings caresses her with his voice: … better ... better ... easy . .. good ... ah!…that's it . .. come on now . . come ... on . . ."; and she, in turn, is shown responding with more and more warmth to his directions. When his pictures have been taken, Hemmings abruptly stalks off, leaving his aroused model stretched out on the studio floor.

As a cogent, if gross, variation on a traditional theme of paintings devoted to the artist at work in his studio, this sequence is reminiscent of the various kinds of distance separating artist and subject, partiacularly the distance created by the inescapable conflict between their motives and expectations. We are led to recall Varmeer or Velasquez, especially the former's "The Artist's Studio," as Hemmings is shown with his back to the camera and in close shot, while his model is seen from over the shoulder, front face, and in medium distance. Like the painting, this shot captures the model in her reverie before the artist in his “Inhuman" intentness. And for all the grunted admonishings and heavy breathings, the whole scene is dominated by a silence as deep and essential as Vermeer's.

Unlike his single sitter, the group of models with whom Hemmings is next shown at work is pictured more ruthlessly—caught by Antonioni's camera in a hard focus that brings out all that is callow, characterless, and stupid in their features. One good look is enough to propel us into a complicity of feeling—in a shared contempt for this team—with Hemmings. Three subjectivities—those of direct, protagonist and audience—are in this instance merged in recoil (even as we are brought willy nilly into sympathy with the heroines of such films as La Notte or Red Desert through the undeniable ungainliness and possible maleficence of what they are surrounded by, despite much about these heroines that might otherwise hold us to an objective or puzzled response). Here, we are led directly to the artist's viewpoint, for Hemmings' indifference to his models' feelings no doubt takes its inspiration from Antonioni’s own coolness—as notorious as Hitchcock's—toward performers. By noting what is characteristic—indeed predictable—of Antonioni in this shot, we may qualify the more severely moralistic-Marxist criticisms that have been levelled at the film. A French film scholar, Annie Goldman, for example, has written that the power over and disdain for the models shown by the photographer is meant to be understood by the audience as "scandalous." Concerning the models themselves, Mrs. Goldman well points to "... the absence of all erotic value in these women whom skinniness is akin to the rigidity of dead bodies and whose pale makeup is responsible for their loss of individuality…[3] But where are we given the cue to blame the photographer for the models' grim preening and deathly self-distortions? They are simply his given materials. What is clear in the contrast between his manner with them and his more benign and sociable response to the group of clownish revellers—their faces also painted—in whom games he joins at the film's end. Before this moment, however, we first note several other games, including the sexual, that we see him—with varying degrees of constraint—drawn into.

Like the game he is led to play with his fans—who barge in on him in the person of two teenage girls. This sequence of the artist and his fans serves as a complement to those of the artist and his models. lt, too, takes place in silence, for even as the girls literally tear at the photographer, they are unable to express what exactly they want from him. Fatter than the models and more directly grasping, they prove equally grotesque. Half to show his contempt, and half in bemused self-defense, Hemmings responds by tearing at their clothes, until all three begin wrestling in an orgiastic play determined by impulses which appear to be as much violent as sexual.

Another curious and sudden threesome. in which Hemmings is one of two men involved this time, is created when he decides to visit his friends across the hall: a painter and his mistress. Unable to discuss his controversial photograph with his editor, who is off on his high, he seeks counsel with this couple and so drops in—to find them busy making love. He is held, before he can back out, by the mistress' glittering eye fixed on him mock-teasingly. In the perspective of Zabriskie Point, we can now observe in these scenes with fans and neighbors an adumbration of the latter film's orgy-in-the-desert sequence, whose regiment of lovers is arranged in variously combined groups. And, in their far from sublimely intimate quality, the scenes from Blow-Up also anticipate the decided ambiguity of treatment of the desert love-in, which comes across as a vision rather more desperate than celebratory.

In the world of Blow-Up, in any case, one aspect of the style of the characters is their easy orientation to ways of sex that are neither private nor personal. As defined by Hemmings and Redgrave in their hurried meeting, the sexual attitudes of all the characters tend to be unromantic and coolly sardonic. In general, the young people act more on reflex than on premeditation. No one lays out structured five-year-plans or plots. As expected, we never see Hemmings preparing to "go out" in any formal way: instead, his world is one in which people randomly drop in and out of scenes.

Except for the presumed slain, gray-haired man in the park and the cranky clerk of an antique shop, none of the people in the film seems to be older than thirty, and most seem to be a good deal younger. A main feeling shared by this world of the young—as it is generally shared by the characters in an Antonioni film—is the desire to be elsewhere: on any turf but the one presently occupied. Thus, everyone is ready for a trip. The young woman who owns the antique shop talks of selling it to afford a flight to ". . Nepal or Morocco ..." The hero keeps wishing for enough cash to permit his going in search of a place where he might be ‘free.” In like manner, the young engineer played by Richard Harris in Red Desert awaits his trip to Brazil where he, too, hopes to be “free." The heroine of Red Desert looks broodingly on the ships in the harbor and the men who sail them. This mass compulsion to flight is the clearest symptom of a time without peace. And, as in times of outright war, relationships remain frankly tentative—pauses along the routes of lone marchers during which messages and news of temporary “Nepals" are relayed. In the antique shop, the object that proves most appropriate to the hero's mood, and that he insists on buying, is a not-very-antique propeller (a found metaphor which will be materialized into the airplane that the hero of Zabriskie Point steals for a flight away from Berkeley). Drugs are, of course, in common use since they provide the most readily accessible of “trips.”

In the course of his search for the mystery woman of the park, Hemmings is drawn into another game of disassociation from the environment: as one of the crowd at a folk rock concert, he watches while the lead performer smashes his guitar and flings part of it to the howling audience. Hemmings happens to grab hold of this prize, and he uses it to fight his way to the street. In largely reflex action, he thus asserts himself as a winner among the crowd. But this is not freedom. Alone on the street, he hurls away the wooden stump with a violent flourish. Again, we are reminded of the involuntary nature of his earlier involvements and his mixed attitude toward them.

Hemmings' rounds through friends' flats and shops and concert halls lead him full circle back to the park where he had first observed the mystery couple, and from which, overnight, the body discovered in his blow-up had disappeared. All along, he had been drawn in quest of the missing body. But he is at last diverted—decisively—from any such further pursuit by another game, the only one we see him joining without reserve.

The film had opened with shots juxtaposing the hero on his solitary jaunt through the streets of London with the buoyant entry on the streets of a youthful band made up and dressed like clowns. In the final scenes, Hemmings and the revellers are brought together when he stops outside the park's tennis court, occupied by two of the band who, without rackets or balls, mimic a game. While their fellows, in the role of spectators, move their heads from side to side to the tempo of the match, the rhythm itself becomes real on the sound track as we hear the sounds of a tennis ball being struck and bouncing on the court—until it is hit out of court to land, it would seem, right at Hemmings' feet. And now, with his full being as a participant rather than as a coolly detached spectator or as an "operator,” Hemmings goes through the motions of scooping up the ball and throwing it back to the players on court, one of whom thanks him before resuming play. Here—in a moment startling in its "peace—Antonioni finds the ideal shot his hero had failed to get to conclude his book of photographs. Then the camera abruptly arcs high and away from Hemmings in a back-zoom which leaves him looking up from the super-green depths of the park—an anonymous and lilliputian figure in a landscape.[4] The hero's complete disappearance from the field in a final trick shot is perhaps ironically suggestive of the one sort of peace ever possible in an absolute sense: that of a total nonhuman blankness.

III

For some critics, the tennis court finale appears so incongruous in tone to the rest of the film as to be sentimental and arbitrary.[5] Yet the sequence fits squarely into the iconography of Antonioni's films, providing an apt parallel, for example, to the concluding shot of one of the earliest major works, Il Grido (The Outcry). In this film, a workingman is displaced from the home base of his existence when the woman he had been living with for many years leaves him, without warning, to marry another man. His subsequent wanderings define not so much a real quest on his part as a circling about his lair in a state of shock. He remains, so to say, too heavyset in character to float free of his anchoring sense of reality and “peace." In the last scene, he stares down from a high tower overlooking his empty home, and, with a cry of total despair over his loss, falls to his death.

Hemmings, too, proves to be on a vain, essentially neurotic, quest. He circles about the fatal spot in the park (emptied of the body Hemmings presumed should be there) in the way the workingman circles about his vacant house. For Hemmings, the missing body signifies the loss of a tangible coordinate in reality apart and beyond the games, put-ons, and role-playing involved in his usual rounds. But since he is pretty much free-floating to begin with, he can ride with his anxiety in a way the earlier hero cannot. And when he joins in the make-believe tennis game, and so helps bring it into existence as that sort of contemporary art work called a "Happening,'' he, in one toss, shucks off that obsession with an anchor point which destroys the protagonist of II Grido. Among the various quests which recur throughout the films, we may also note that of the heroine of L'Avventura, for her girlfriend mysteriously disappeared from an island. This quest also proves both vain and equivocal in nature, as it becomes clear that what the heroine most seeks is reassurance concerning a friendship she had valued as central to her existence. Indeed, her quest leads to shocks concerning not only her ideals of friendship but also those to do with romantic love–both of which kinds of experience she is brought to seeing in a changed perspective.

From the sort of changed perspectives opened up by a film like L'Avventura, we turn with the Happening to an experience that radically qualifies our traditional standards and expectations of art. The Happening neutralizes our sense of the sacrosanct authority of the artist, and our sense of the relationship of the audience to his work, and finally our sense of art in relation to reality. Walls are broken down in the illusion of the game, as what is created through the illusion is another Elsewhere. The real world—which is to say the world from which Everyman presently feels as alienated as the old artist hero—now becomes merely a starting point. a "source. for Everyman as well as for the artist, as both meet in motive and act in the Happening, “not-always-repugnant-monsters” together! Blow-Up thus builds to a scene in which the analogous situation between artist and Everyman, as felt by Antonioni, is made dramatically explicit. The scene falls in place in the context of the whole film as a desperate, fleeting pastoral.

T. J. Ross

Notes

1 Julio Cortizar, Blow-Up and Other Stories (New York: Collier Books, 1968), p. 100.

2 Ibid., pp. 108-109.

3 Annie Goldman. "On Blow-Up," Tri Quarterly, Winter, 1968. p. 64.

4 This scene was shot on location, but that the real park serves only as a source for the illusion sought—the real world of the location standing in relation. to the filmed scene as, say, his sources served Shakespeare for his plays—is emphasized through the much-publicised fact of Antonioni, having had the grass painted over to his specifications. The whole fanciful play in this scene of sound effect and color scheme suggests how much the director himself—like his young protagonist—has here most freely entered into the spirit of the game.

5 In an interesting essay titled "Blow-Up" in December, 9 (Chicago, 1967). 142, F. A. Macklin, for example, suggests that this scene “… changes the mood and concentration of the film. The clowns seem out of another world . . ." For a contrasting view, on the scene as wholly negative in its connotations, as an image of "disintegration," see Thomas Hemacki, "Antonioni and the Imagery of Disintegration," Film Heritage, Spring, 1970, pp. 13-22.