Karl Gerstner

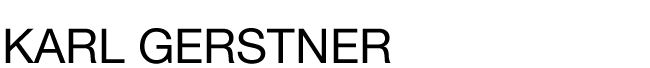

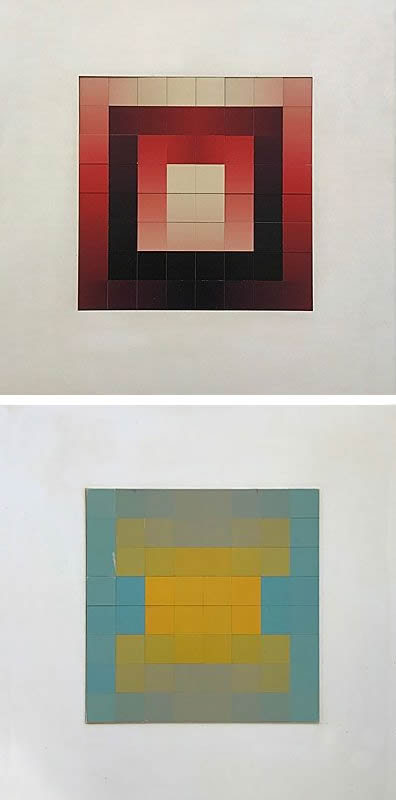

Carro 64, collage of lacquered plates on aluminum, 1964.

How Ever Did You Get the Idea? Isn't that the question artists are most frequently asked at the previews of their shows? ln my opinion, it rates an answer, though I am embarrassed every time I hear it. Perhaps because the questioner's tone reveals great expectations that I am loath to disappoint.

When art consumers go to a show, they see pictures in the "finished" state—almost as if they had been conjured up out of nothing. Actually, they are no more than landmarks in a process that develops in a series of small steps. (Let us get this clear I am speaking exclusively of myself and for myself. How it is with other artists is a different story.)

I shall forestall the obvious question and describe the process in an entirely matter-of-fact way, taking as an example the idea of carro 64 (a brand name, as we shall see). The difficulties arise already—or, perhaps, chiefly—at the very beginning: in fact, there is no beginning. I did not invent the problem: I merely faced up to it. And before that I did a lot of things that were not directly connected with carro 64 but led up to it.

Changeable Pictures

The first idea at the root of carro 64 was to make pictures that could change. How it occurred to me would take a separate essay. Suffice it to say that it was quite by chance. But I have often made capital out of chance and mischance. I mean: I make no bones about saying in retrospect that what I did was on purpose.

"The picture is left unfinished intentionally; the intention to be seen as part of the design. I select the elements and determine the regularity of their arrangement. The arrangement itself . . . is up to the viewer . .. He adds his own ideas to mine, perhaps without taking mine into account. . . . He is not a passive admirer but an active partner. As designer, my starting point is the conviction that nobody can be excluded from this partnership; nobody is totally devoid of talent just as neither I nor anyone else can count on an infinite talent." (“Bilder machen heuter in "Spiral," No. 8, Internationale Zeitschrift fur Kunst and Literatur. Spiral Press Verlag, Bern, 1960.)

The picture that can change "is not a picture in the usual sense of the word, namely a definite, accomplished fact. On the contrary, it always constitutes a group of possibilities, of variants involving the same elements. The transformation does not concern an initial theme, an 'original.' What is original in these works is rather the nature of their structure, the law of their creation. That law is formulated so that the elements are not fixed in a definitive design but in a system of relationships. The essential feature is that the framework of the system can contain not merely one 'composition' but an infinite number of equally valid 'constellations.' Here equally valid means that each constellation is just as original as its source or its law. Each reflects a different aspect or, as Mary Vieira says, a different moment." ("Kalte Kunst?". Arthur Niggli Verlag, Teufen. 1957.)

Ed Sommer, in "Art International" April 1966, posed the following question—and how right he was to do so! "For whom are these combination objects intended? The Sunday combination maker, successor to the Sunday painter? If so, it must be borne in mind that nobody ever understood less about art than the Sunday artist. In that case, even the educational value of the objects would be extremely doubtful."

"No. Strip reliefs are not educational aids. Not art ex cathedra. The viewer is not allotted the role of pupil. Nor of the Sunday amateur in any shape or form. On the contrary, the viewer completes the picture that the designer proposes as a project. Combinations are not a matter for experts or laymen, but for the intelligence. (And what about instinct?The eternal question asked before a work of art, to which the mathematician Andreas Speiser replied: 'Instinct . . . as ossified intellect, as thinking become a mere habit . ..)." ("50 Reihen-Reliefs," by K. Gerstner. Invitation to the Show, Op-Art-Galeria, Esslingen, 1966.)

Here is a passage from a letter by Professor Kummer, of Berne, a well-known scholar of law. My pictures, he wrote, posed a juridical problem: Where does the designer's copyright to his work end and where does the viewer's begin? I am glad to see a scholar take the trouble to ponder that question.

Programmed Pictures

The second idea involved in carro 64 is the programming of pictures. It is the practical outcome of making pictures changeable. In fact, if the structure is to be maintained through the modification, all the possible parameters must be definitely interrelated. The picture as a whole; as a total, complete unity; as a formula that remains constant with co-ordinates that are variable. I wrote a small book analyzing this matter, "Kalte Kunst?". Arthur Niggli Verlag.

I had a dim recollection of what Paul Gredinger said about "structural unity from the mental vision to the tangible experience" (or words to that effect).

That brought me up against the problem of introducing rational criteria where (evidently or presumably?) nobody had yet suspected their existence—in the color. I wanted to give up using color topologically, as a means of stressing formal structures; I wanted—willy-nilly (simply on account of the changeability)—to achieve a procedure in which color had an intrinsic place; in which it became part of the structure.

The most obvious means of doing this was to use variable color structures with a minimum of formal definition. And of these the most obvious was to set color series in a squared grating. In other words, in squares ("carres" in French ). That is where, through a misunderstanding, "carro came from—actually, it means "cart.” The first versions, with 28 or more color steps, date back to 1956.

Now I am coming to the point. The carro 64 Idea. The objective: to reduce the color series to 16 steps—an optimum minimum, as should appear from what follows—with every color repeated four times.

The result with these 16 x 4 elements to execute not only all the chance variations (those in any case), interlacings, and combinations, but nearly all the symmetrical basic operations as well. The carro 64 formula served not only for a great many different arrangements but also for any number of different color versions. So far there have been about a score of these, including one black-and-white.

The Mechanic's Contribution. “If the design becomes the program, the material is the basis. This involves a perfect knowledge of the material. Color, proportions, dimensions. What other parameters are there? What are the components? To discover this is also part of the design." ("Strukture und Bewegung," in "Programme entwerfen” Arthur Niggli Verlag, Teufen, 1963.)

I wanted to make the carrot not only colored but plastic, too. In other words, to apply the 16 color steps to 16 carros of different height. The mechanic turned the carro in the corresponding direction. When he brought it back, I was fascinated by the play of light in the grooves caused by the rotation. I didn't want to lay on any more colors.

Thus the mechanic helped me to produce another group of pictures—the Texture Pictures. But that has nothing to do with the subject we are dealing with.

Multiplied Pictures

Changeable and programmed pictures obviously have no place in a museum. They are meant not only to be looked at but also to be utilized. (And what museum would have the facilities for that?) Therefore, carro 64 had to be produced in a large number of copies, so that it could reach the people. But how?

"My aim is not to make pictures, at least not finished pictures. It is to produce a design, a plan, that can by its very nature be executed any number of times. By a carpenter, a painter, a mechanic. It involves virtually no personal handwriting. The idea alone is personal—and what the user makes of it.

Viewed from this angle, the problem of reproduction so to say solves itself. Whereas a lithograph made after an original contains only a certain percentage of the initial originality, my objects have no original.

This is the point of a multiple like carro 64. Being changeable, it exists in a different version every time it is executed. Every purchaser is able to make an original for himself, no matter in how many copies the picture is produced." ("Kunst, massen- and masgefertigt" in "Schweizer Spiegel," No. 6, 1968.)

"carro 64 is 'a mass-produced original." George Staempfli neglected this aspect of carro 64. He wanted the entire edition he had ordered to be arranged in an identical fashion ("as it says in the prospectus"). So he had to pay $ 8 duty on each copy in New York. Had he followed my advice and arranged each one differently from the rest, all of them would have been accepted as originals under the customs regulations and imported duty-free as "genuine" works of art.

"Incidentally, a dispute with the Customs is going on in New York just now as to what heading variable multiples should be rated under. There is obviously a lacuna In the regulations. And the question is developing into a problem because more and more objects of that sort are being produced. You can see that the criteria of a new artform crystallize first in the legislation, then in the customs tariff, and only after that (if ever) in the history of art." ("Kunst, massen-und masgefertigt" in "Schweizer Spiegel," No. 6, 1968.)

The idea of carro 64 was not enough: what was also needed was the idea of how to produce it in quantity. In fact, the color steps lie so close together that fluctuations in the production process for each single color are greater than between one step and the next. The solution was to print all 16 carros in a single run: quite literally, to produce with a printing machine by the color printing process.

The carros themselves are made up of printing elements—setting sticks which for technical reasons must be almost absolutely exact. These are locked in a form and hung on the wall. So they can be dismantled and changed at any time.

Changeable pictures, programmed pictures, multiplied pictures. That's fine! Art is a commodity and its value depends on what the user makes of it But how is the presumptive user to find it? For, of course, he never enters an art gallery. Unless he belongs to the initiated one per thousand.

Department-Store Picture

From the very start, my idea was to put Carro 64 on sale where people go to buy things—namely, in department stores. For that purpose, I took my prototype carro to Peter Kaufmann, the enlightened manager of Globus department store in Zurich. But I was too far ahead of the times, and the pictures, though mass-produced, were too expensive. Later—in 1962—Christian Holzapfel took it upon himself to bring out carro 64 in 120 copies and distribute them through his furniture dealers.

The second series of carro 64 (in different colors) was brought out in 1965 by Georges Staempfli, a professional, who exhibited my objects for the first time in New York. He was also responsible for the idea of selling works of art by mail. And what I simply couldn't believe actually happened: customers from Boston to San Francisco sent in their orders for carro 64 enclosing their checks. The edition was sold out in no time." "Kunst, massen- and masgefertigt in "Schweizer Spiegel" No. 6, 1968.)

If the whole story has to be told, I would have to say, too, that carro 64 was also published in a Tokyo version (20 copies by the Tokyo Gallery in 1966) and a Genoa version (20 copies by the Galleria del Deposito in 1965).

So you can see that my wish was not fulfilled. The carros have continued to pass through the official art channels. If I say this a bit wistfully, It does not mean that I am ungrateful. Art has often been shown in department stores—the first time, many years ago. But that is not what interests me. What I am set on is department-store art. Group Pictures. What I like is not only to program my pictures but to display the programme too.

I kept sixteen copies of George Staempfli’s edition of 120 and declared them as an (unchargeable) group picture containing a "cyclic permutation."

Incidentally, I am often asked if my changeable pictures have actually been changed. Well they have. Not all to the same extent, of course. One of the most alert observers, Architect Rolf Gutmann, of Zurich. sees carro 64 as spiritually related to his own problems: the changeable structure as a principle of architecture and town planning. He explained the relationship in the Swiss Pavilion at the Milan Triennale of 1968. He also told me the story of a businessman who stopped changing this carro for a very special reason: the last constellation was the work of his small son shortly before he died.

From the carro Idea: the Color Reliefs. Hein Stunke was eager to publish several screen-printed carro constellations in his "Portfolio Edition." I wasn't very keen on that because the method of reproduction contrasted with the multiple-idea of carro, 64.

On the other hand, his suggestion gave me a chance to find out what effect the carro would make in larger formats. (I have always regretted that my pictures, having to be so exact, have always been small and model-like.) But it raised problems that could not be solved. First, at the printer's: he was unable to print the colors with the necessary precision. Second, when Hein Stunke proposed to print the colors separately and stick them together, it was too much for the binder. These difficulties led me to set the colors one above the other instead of side by side, in such a way that the underlying colors were always visible around the edge. This made it less important for the binder to be an absolutely precise job.

The edition never materialized. Instead, there was a series of Color Reliefs that I was able to execute in almost any size. What struck—and pleased—me in retrospect in the Color Reliefs was that the superposition of the colors produced a greater natural density than when they were placed side by side (which Mondrian, as everyone knows, turned into a ritual to be observed even in laying on the color). There is a continuous relationship between each color and its next-door neighbours.

Further, the harmonic phenomenon of the color series is stressed. Though the colors differ very slightly from one step to the next—in extreme cases they are almost impossible to distinguish—those at each end may (in the extreme case) be complementary. A 16-row work for instance, is not so much a scale of sixteen notes as a paradox, monochrome polychrome. People have often tried to change the Color Reliefs in the same way as the carros, but they cannot be changed.

"The picture as the design of a whole, a total complete unity; and, on the other hand, the unity viewed as a constellation of changeable magnitudes: The challenge concerns not only the picture, which in the end is really changeable, but the designing technique, too. The only constant of the picture is its idea. The changeable factors are the proportions, the colors—they are changeable inside their system—and the measurements, which are fortuitous. . .

What I want is to be able to dispose not only of the obviously combinable parts but also of all those that could possibly be combined, a catalog of all the decisive pieces and their parts for picture making. My objective is not merely the individual solution, however complex it may be, but the catalog of all imaginable solutions: what might be called a catalog of latent, future pictures." (“Bilder machen heute?" in "Spirale," No. 8, Internationale Zeitschrift fur Kunst and Literatur. Spiral Press Verlag, Berne, 1950.) The idea that derived from the Color Reliefs idea was Color Sculpture: a two-faced relief intended for hanging not on the wall but in space, and to be accessible from all sides.

Low-priced Pictures

Even if the experiment of selling art as a commodity had been a success, a problem—the most important one—would still remain to be solved. It would not suffice to bring the consumer face to face with the commodity: one would have to create a demand.

"Today the potential art-purchaser went on a buying spree. He bought himself a car, a television set, a dish-washing machine, a new sitting-room suite. . . . But the idea of buying a picture didn't enter his head, and no one tried to make it. (Four-color prints of Klee's paintings don't count of course.) Is there no demand because of inadequate publicity? (Art as the symbol of Purchasing-power Classes 2 and 3.) Or should this be finally a task for educators? An educational business, in fact? Is a Bertelsmann what the trade needs?

Art in Bertelsmann's purlieus.' that makes the problem one of price. "The price of an artwork determines who will buy it—an unpleasant fact. For the ownership of art should not—or, at any rate, not only—be a question of money. A work of art—a product of the spirit—must perhaps be exclusive: as exclusive as possible, because that H its criterion. But it should be accessible to all—like any other product of the spirit." ("Was darf Kunst kosten?" preface to the catalog "ars multiplicata," Kunsthalle, Cologne, 1958.) I have heard the same words time and again: "Multiples: a fine idea. But why must they be so expensive?" ( Holzapfels first carro’s cost DM 395; Staempfli's, DM 500; the others, DM 600.)

It was this reproachful question that led me to produce a popular edition of the carros—actually I was sick and tired of the idea—a do-it-yourself edition (packaged like a Braun kitchen appliance) in three versions (green, orange, and violet) of 250 copies each published by Denise Rene & Hans Mayer, Paris & Krefeld. This edition of the carros ended up by costing more to produce than had been estimated, but the price per copy was DM 250.

Multi-carros. The production of the popular edition led in turn to another idea. Mass production placed at my disposal elements with which I could make not only single carros but also carros out of carros: double carros, triple carros, carro solids, carro spaces—an entire carro world. This, in my opinion, has brought me to the end of the carro idea once and for all.