'Your Golden Hair, Margarete': About Anselm Kiefer's Germanness: Corrine Robins

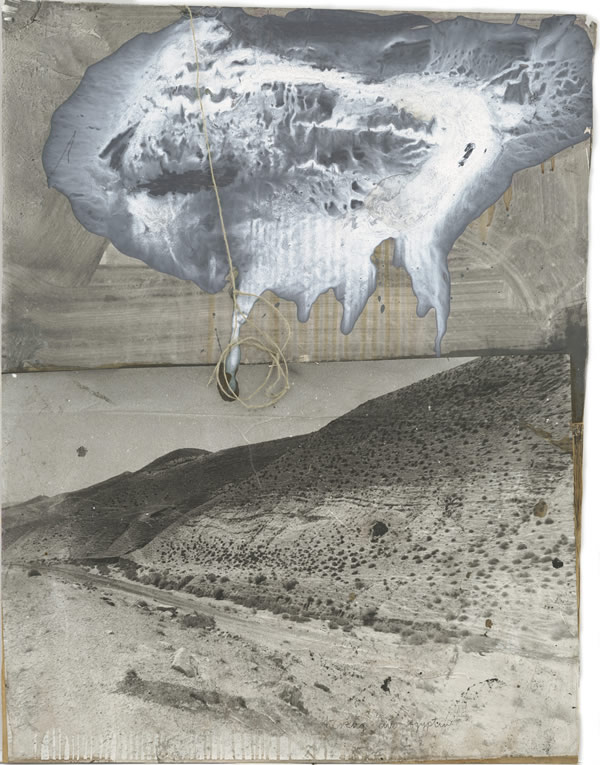

Anselm Kiefer. Auszug aus Aegypten (Departure from Egypt) 1984.

What repels one so much about Anselm Kiefer's work is its German-ness—the very Germanness that one must acknowledge is also a measure of its success in terms of this artist's own aspirations of greatness. The artist is always very specific in his insistence upon his national identity. For example, in his 1976 "autobiography"—a list of words describing his inner and outer life—are the words "black forest, border, Adolf Hitler, Study with Joseph Beuys, Düsseldorf, Robert Wagner and Parsifal, works of the scorched earth.”[1] Mark Rosenthal, in his very scholarly exhibition catalogue essay, explains, "The blackness of the burnt landscape is Kiefer's characteristic tonality: Kiefer claims that only the French use a range of colors; and that he, belonging to the German people, is unfamiliar with such practices.”[2] And indeed, the artist's emphasis upon landscape—even to painting the words "my land" across a canvas—and his later loving depiction of Nazi buildings, would all seem to be in keeping with this nationalistic stance. It seems sensible, therefore, to take Kiefer's Germanness at his own word.

But what do we Americans know about this kind of love of land, this concept of blood and soil, of blood for soil, which is an age-old German preoccupation, the preoccupation of a small, energetic country with few roads to the sea? We are, or were for most of our history, a country of vast open spaces, of new frontiers, of places to move on to. Has this old idea of blood and soil now become necessary information for Americans, who are in the process of discovering we live in a small world, that oceans no longer mean much and Europe is, in fact, next door? In the past few years, it has become an accepted truism that Europe, indeed the whole world, lives with us inside our own country. The other side of the issue is that we, along with much of the rest of the world, currently seem to be striving after a new nationalism, and countries everywhere seem to be becoming more competitive. It would seem that people today travel first to comparison shop, and then, second, with the idea of discovering themselves and their differences. The spirit of the time seems to be vive la difference!

And it may be the exotic difference of his Germanness that fascinates people with Anselm Kiefer's work. For almost ten years, the artist has been a landscape painter of war-torn earth, deserted buildings, and the dead dreams of a Third Reich that was destroyed before he was born. A recent, enormous traveling exhibition leaves few doubts about Kiefer's appeal, major aesthetic stance, or historical preoccupations. As Mark Rosenthal observes in the exhibition catalogue, "Landscape is the central motif by which he [Kiefer] expresses a disintegrating, violated, or suffering condition of Germany; for much of his career, the blackened burnt landscape has dominated his subject matter.”[3] This "burnt landscape" comprises a past that, however, I believe, lives in an equivocal relationship with present-day Germany.

The Kiefer exhibition has been a crowd-pleaser and a huge popular success in Chicago, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia, before coming to New York. Perhaps it's more of a success (certainly it is an exhibition with a far wider traveling schedule) than was his mentor Joseph Beuys's exhibition ten years earlier. It was back in 1979 that Beuys, the German conceptual artist, introduced the themes of German art to America in an exhibition/installation that took over the whole of the Guggenheim Museum. For two months the lights in the museum were turned down and the heat was turned off to keep the mounds of fat from spoiling. Color in the show consisted almost entirely of gray felt, white-gray slabs of fat, wood, cobalt, a bit of copper in the form of rods, and touches of hare's blood. As I wrote at the time, "What Beuys may have borrowed from Minimalism, he borrowed deliberately. The shadow of the concentration camp hung over the ramps of the Guggenheim but as we marched down the ramp, many people felt what they were seeing was the camps from the point of view of the guards who stood and watched the Jews die, and that this was not being evoked in the spirit of 'never again.' “[4]

Today, ten years later, Anselm Kiefer, the brightest of the group of artists sometimes dubbed "Beuys' boys," seems to be drawing upon a similar historical German consciousness. But in his paintings from 1979 through 1983, Kiefer attacks the problems of German guilt in a way that would perhaps be impossible for anyone who lived through and participated in the Nazi era, as did Beuys, who served as a Stuka pilot in the Second World War.

The connection between Beuys and Kiefer began, as one between teacher and student, when, in 1970, Kiefer was accepted to study informally with Beuys in Düsseldorf. Beuys encouraged the younger German artist both in his painting and his preoccupation with the myths of German history and nationalism. In 1972, Joseph Beuys gave slides of Anselm Kiefer's work to the dealer Michael Werner, who proceeded to show the artist's work for the next seven years.[5] In terms of its specificity to the period, Kiefer's work certainly seemed preoccupied with German history in a more literal way than the older artist's. Beuys's use of the materials of fat and felt was offered as part of his, Joseph Beuys's, own personal mythology. European critics, Beuys told an American interviewer, "interpret my work as having to do with the holocaust—fat with catastrophe, with death—gray color and destruction. But I am not interested in allusion. I am interested in Change."[6] A conceptual artist, Beuys was primarily a maker of objects and very much a public figure, with his felt hat worn indoors and out and his staff, cane, or "energy stick" as his trademarks. Throughout the '70s, he staged performances and gave innumerable lectures about art and the artist (i.e. himself) as instruments of social change.

Anselm Kiefer, by contrast, is a painter who shuns the public arena, gives few interviews, and does not allow himself to be photographed. Both men, however, were involved with the idea of change. Kiefer, it would seem, has been preoccupied with the idea of physically changing the nature of his materials, as well as with issues of national guilt. And where Beuys played out in public his role of artist as shaman, Kiefer sees the artist as a quiet alchemist, working away from the public, seeking a more and more forceful relationship with his materials. In the '80s, Mark Rosenthal writes, Kiefer "subjected paintings to burning and melting, exploring the physical-cum-spiritual character of his materials. The canvas became a fetishistic object for this alchemist-painter, from which a New World could emerge, notwithstanding the alchemical potential for 'terrible' and 'sinister' experiences of 'blackness,' of spiritual death, of descent into hell.”[7]

The words "spiritual death and descent into hell," though used in terms of alchemy, also refer to the fact that, from the late '70s on, Kiefer has set out to summon up a mourning world of the Third Reich in his study of the aftermath of Germany's "spiritual greatness" and defeat. In Germany in the early '70s, this kind of subject matter was shunned almost by general consent. Indeed, it was a policy decision of the American government and the Germans themselves after the Second World War that the subject of the Third Reich was better buried. In the mid-'60s and early '70s, however, young German writers and filmmakers began to ask what had happened in the period, and the veil of silence began to lift. The question of German guilt that had been put away with the Nuremberg trials was first brought up again nation-wide when an American television series on the Holocaust was aired throughout West Germany in January 1979, and subsequently in Austria and France. The program was watched in Germany alone by an audience of 20 million people.[8] And it is in this context that Kiefer's paintings of 1979 and 1980 join the concern of popular culture with the Holocaust to a new, mourning exploration of the beauty and symbolic weight of National Socialist architecture—those dream buildings, many of them later destroyed.

When Joseph Beuys returned to dismantle his Guggenheim exhibition in 1980, the artist held an evening performance at Cooper Union entitled "The Theory of Social Sculpture," in which the artist instituted a dialogue with his overflow audience in the Great Hall. Beuys's English was fluent and he encouraged and fielded questions non-stop until someone asked if he didn't feel any guilt, particularly for his role as a pilot in the German army during the Second World War. Beuys asked for the question to be repeated, and it was. Then the artist apologized for his lack of English and requested his translator to translate the question. "No," Beuys said, after listening to the German version. It seemed to Beuys that the translator could not have gotten the question right. Then, after it was posed in English for a third time, Beuys answered softly, "Of course. We are all—everyone is guilty.”[9] Ergo, as we all know, when everyone is guilty, no one is guilty.

The current Kiefer exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art started a year and a half ago in Chicago and features (one could almost see it as built around) the paintings based on Paul Celan's famous concentration-camp poem "Fugue of Death," written in a camp in 1945 and published in 1952. The poem is given in its entirety in the catalogue,[10] and quotes from it are written on Kiefer's canvases or, at the least, incorporated into the titles of several major works. In Celan's poem, to some extent, and throughout an extraordinary series of Kiefer paintings, the golden-haired Margarete and the ashen-haired Shulamite woman personify Germany and the Jews (the idea being that the Shulamite's black hair is now ashen from burning). All these paintings date from 1980 through 1983, a period in Germany that saw the question of German guilt and what the loss of its Jews meant to Germany discussed in great detail for the first time. Rosenthal marvels at Kiefer's daring espousal of the view that he feels is carried out by these paintings, that "Germany maimed itself and its civilization by destroying its Jewish members, and so by frequently alluding to both figures, he [Kiefer] attempts to make Germany whole again.”[11] In fact, Anselm Kiefer in these works is dealing with a suddenly (and I suspect, briefly) popular German subject matter that was being canvased extensively by the popular press.

Several works from the series, with titles such as Your Golden Hair, Margaret. (1981), incorporate straw into their surfaces to symbolize "golden" hair. The artist began using straw in his landscape paintings with no particular theme in mind. Then it seemed quite naturally to lend itself to his Margarete paintings, many of which center around the Celan lines, "A man lives in the house, he plays with serpents, he writes/he writes when dusk falls in Germany your Golden hair Margarete/your ashen hair Shulamith." Kiefer takes straw and places it beside a black painted curve, and thus we arrive at the world of racial stereotypes with a vengeance. By way of contrast, Celan uses the image of golden hair quite differently in his poem Aspen Tree, which begins: "Aspen tree, your leaves glance white into dark./My mother's hair was never white. Dandelion so green in the Ukraine./My yellow haired mother did not come home.”[12]

Kiefer's most powerful painting on the theme is one in which there is no trace of either Margarete or Shulamite except the latter's name. Shulamite (1983) is a large painting of the inside of a great, tunnel-like, dark hall full of black shrouded windows, in which we perceive through a series of arched walls an altar where the painting suggests fire once burned. Across the top of the painting is written the word "Shulamith" and it is hard not to see the crypt-like building with its blackened ceiling in terms of the inside of a gigantic oven and/or funeral pyre. The catalogue tells as that Kiefer took a design for the Funeral Hall for the Great German Soldiers as a source for the painting, and converted it to stand as a memorial to the Jewish woman, and, by extension, the six million dead. The painting is very moving, as are the Margarete paintings and other landscape paintings incorporating straw, such as Nuremberg (1982) and Wayland's Song with Wing. In all these works, the themes of death and blackened soil are masterfully handled.

"Masterfully handled," a moving masterwork the paintings bring such words to mind. Also, power. Looking at Shulamite, in particular, reminds me—as do all the more powerful paintings in the exhibition, which I saw both in Philadelphia and New York—of the Celan line, "Death is a master from Germany." In his exhibition, Kiefer presents a glorified, mourned-over past that seduces immediately by its presentation of the power of the powerful, powerful even in their fall. Even while half in mourning, Kiefer's grandiose canvases sport their heavy Germanic coloring with pride, to offer us yet another look at "fascinating fascism," to use Susan Sontag's term.

During the tenure of the exhibit, the high-ceilinged rooms of the Philadelphia Museum became a vast, cavern-like hall of art. Kiefer's books were placed on stands and, on the hour, two museum docents stood by turning their pages for visitors. Everything was arranged to lead visitors to the big paintings hung in the center of the room, and, indeed, the small early watercolors seemed diminished by the space. Even the lead and steel sculpture, Palette With Wings, seemed a rather eccentric piece, positioned to serve as little more than a pointer leading to the unforgettable giant relief paintings Iron Path, The Book, and The Red Sea. These three monumental works derive their power from the artist's manipulation of the canvas surface, his employing of oil, acrylic, emulsion, iron, and lead in the interest of creating landscape, a landscape specifically drawn from the color and the look of the fields around the artist's studio in Buchen. For Kiefer, landscape stands for Germany—not the bustling West Germany of today, but a long-gone symbolic Germany that in his mind stands for, and perhaps is, the world.

In The Book, according to the catalogue, Kiefer "presents a tangible manifestation—a forged, lead book—before an illusionistic concept of the infinite . . . presents the book as an inheritor of great tradition of profoundly held prophecy and human thought." And then we learn, a few lines later, that it (this book) is also "a richly evocative theatrical prop." [13] To my way of thinking, the lead book draws its power from the heaviness of the metal. The book becomes a tomb of dead knowledge, a marking of loss, a commemoration of vanished knowledge in a lost, i.e. forgotten, landscape. Rosenthal in the catalogue also suggests Kiefer is using the form in an alchemical/symbolic fashion to summon up the thousands of books burned by Hitler's Third Reich. And in a more literal sense, perhaps "the book" could refer to "the people of the book," the lost Jews, and could be taken for their commemorative stone.

Kiefer's Iron Path, also installed to the greatest effect in Philadelphia, is a nine and a half-by twelve foot painting whose vertical tracks converge near the top, the horizon line of the painting. Attached to the tracks are iron climbing shoes, and so these tracks are a physical and spiritual path moving across the land and, at the same time, are given a physical dimension by the introduction of another kind of perspective to the tracks' old-fashioned composition and classical two-point perspective. The Red Sea, another multi-leveled symbolic painting, depicts an iron bathtub above which hangs the outline of a glass plate, set against his usual scarred fields. In Philadelphia, all the other paintings, sculpture, and earlier watercolors were dwarfed by the above works, exhibited in a cluster with Midgard, Nuremberg, and Nigredo. And in that setting, there seemed to be a sameness about the work, despite the artist's manipulation of different materials, which emphasized the narrowness of Kiefer's visual range compared to the breadth of the symbolic meaning placed upon it.

The show in the temporary exhibition galleries at the Museum of Modern Art, which many people (this writer among them) feared would prove to be a wholly inadequate space, actually afforded a cleaner, more comprehensive look at the range of the work. Kiefer is constantly trying to introduce new materials into his art. At the Modern, the very largest paintings and the free-standing sculpture were installed in a room on the third floor. The downstairs, temporary installation galleries were opened up into one large room so that the early works—his watercolors and the 1970 paintings such as Resurrexit and even the larger Germany's Spiritual Heroes—could be seen separately, in and of themselves.

There were also some apt pairings of paintings, so that the 1980-82 interiors based on works of Nazi architecture could be seen close by and in the context of the 1973 depiction of the inside of a wood hall decorated with burning torches and the title, "Germany's Spiritual Heroes," scrawled in German across the top. And, from the same period, a work titled Ways of Worldly Wisdom, which the catalogue explains thus: "Taken from either dictionaries or books about the Third Reich...Kiefer's depictions recall Gerhard Richter's 48 Portraits series of 1971-72 and Andy Warhol's many celebrity portraits from the 1970s onward. Like the American artist, Kiefer looks at the heroes of his country in a deadpan way: the result is a kind of jingoism in which these individuals take on the characters of gods. The portrayals by both Warhol and Kiefer leave their subjects slightly hollowed, all surface and no inner core.”[14] In his Times article, Paul Taylor writes, "Although his paintings have the Sturm und Drang of archetypal German art, Kiefer doesn't see himself as a nationalistic artist”;[15] and, in fact, Andy Warhol and Joseph Beuys are the two artists he considers most influential to his work.[16] Thus, in keeping with the artist's own words, it seems an inescapable conclusion that rather than being ironic, Kiefer's approach to and treatment of both German nationalism and the Holocaust is that of someone artistically treating and making use of a media event.

Notes

1 Mark Rosenthal, Anselm Kiefer. The Art Institute of Chicago and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1987, 11.

2 Rosenthal, 32.

3 Rosenthal, 133.

4 Robins, ‘The Double Message or Joseph Beuys,” New York Arts Journal. Nov 1980

5 Paul Taylor, "Painter of the Apocalypse.' New York Times Magazine, Oct. 16, 1988, 102.

6 Gerald Marzorati, "Beuys Will Be Beuys,” The Soho Weekly News, Nov. 1, 1979, 8

7 Rosenthal, 127.

8 Jeffrey Herf, “The 'Holocaust' Reception in West Germany," New German Critique. 19 (Winter 1980). 30-52 The New German Critique devoted its Winter and Spring. 19th and 20th issues to the subject 'Germans and Jews ' Issue 19 devotes a goodly amount of space to examining the incredible effect that the 'Holocaust" TV series had on the German population as well as throughout Western Europe during 1979 and 1980, and documents the fact that discussions of the Holocaust occupied a large segment of the popular press throughout the year.

9 Robins, op. cit.

10 The poem and its meaning are discussed in detail in Rosenthal (95-97), which notes the fact that Celan himself committed suicide in 1970. It seems to this writer that that has been a pattern for many of the concentration camp writers/victims, from Tadeusz Borowski, the Polish author of a group of stories titled This Way for the Gas, Ladles and Gentlemen, to Primo Levi last year.

11 See Note 10.

12 Translated by Michael Hamburger in Another Republic Charles Simic and Mark Strand, eds. (New York: Ecco Press, 1976), 182.

13 Rosenthal, 133.

14 Rosenthal, 51.

15 Taylor, 80.

16 Taylor, 80.