The Readability of the World: Zdenek Felix

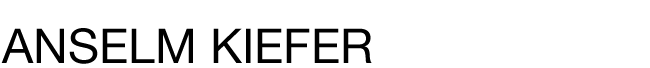

Anselm Kiefer. Die Überschwemmung Heidelbergs I, (The Flooding of Heidelberg I), 1969.

Compared to AnseIm Kiefer’s monumental paintings and the heavy lead sculptures of the last few years, his books have attracted relatively little attention. Yet they represent a considerable output, and have assumed an important position in Kiefer’s oeuvre. Quite early in his career, from the mid-seventies on, the artist regularly included his book-objects along with paintings and woodcuts in his more important exhibitions, an indication of the significance he attaches to them.

He did so for the exhibition entitled Margarete—Sulamith, which this writer helped the artist organize at the Folkwang Museum in Essen in 1981. During several visits to the old schoolhouse in Hornbach where Kiefer worked at the time, we selected for the exhibition a topical group of works he had recently completed, whose theme was Paul Celan's tragic poem "Todesfuge" (Fugue of Death). A few early, mostly large paintings, whose subject matter the painter considered relevant to the theme of the exhibition, were added. Yet of no less importance were the heavy fascicules, painted over with tar that were kept in the attic, and which continued to seem strange even after repeated visits. A group of these books, displayed in glass cases with slanted fronts, enriched the exhibition in Essen and left no doubt to what extent the artist considered the two disciplines—painting and making books—inseparable components of his work.

The writer Walter Grasskamp aptly called the attic in Hornbach “the patrimony storehouse" because Kiefer kept his books there for a while and arranged clay, lead, water, dried branches, toy tanks, and palettes in ways that would later serve as models for his photographs and paintings.[1] Indeed, Kiefer used the large space as a sort of warehouse, in which rote book learning—as well as material literary and historical, religious and mythological—were woven into an expressive iconography. "Here Kiefer staged his own 19th century, for the mythical figures and subjects which enliven his attic pictures are younger than they seem: Satanism, evoked in Quaternitat (1973. private collection), reached its high point in the century of the Fleurs du Mal and Kiefer revived Parsfal and the Nibelung saga not so much from their literary incarnations, but rather by going back to Richard Wagner's treatment of them.”[2]

No matter how decisive the Wagnerian iconography may be in some of the early works, it tends to be infiltrated by another metabasis. What matters in these works is not only the radical vision of Wagner's mise-en-scene, but the way in which his works were used and misused under the aesthetic monopoly exercised by the Third Reich, that is to say, as accompaniment to ideologically veiled mass rallies and as witness to a death cult as monstrous as it was obscure. "The Wagner issue"—the road the composer took from artistic revolution to public reaction—is part of the iconography of these early pictures, just as Siegfried, Hagen, and Brunhilde are inseparable from the old German legends.

Precisely because Nazi ideology inverted and thus deformed these myths, a return today to the original material can succeed only by taking the deformation into account. This is especially pertinent where now it is a question of reactivating and rationalizing these myths, of securing them for the present, which is to say, by disclosing their structures as paradigms of a "general and systematic interpretation of the world" (Manfred Frank).[3] Kiefer, who on principle will not give up the legends as source material, does not hesitate to touch the "hot iron" of Germany's most recent past in order to deconstruct it in his work and to interpret it anew still and always as the past with which it is impossible to come to terms.

Looked at this way Kiefer's preoccupation with German mythology and particularly with the fateful recent past, in which the almost two thousand years of the German people's existence are concentrated as if under a burning glass, seems the result of a decision based in equal measure upon artistic and personal, thus autobiographical, reasons. Whatever one's reaction to the decision may be, Kiefer could only invest his painting with a more profound meaning when concerning himself with the Third Reich, which had become almost an obsession. Taking a moral stance and condemning this past is not enough for tackling one's own story. In this sense, Kiefer's "historical search," as the American writer Mark Rosenthal has called it,[4] is also a search for his own roots and the ground in which they grew. Without such traumatic work, Kiefer would probably not have been able later to turn credibly to other historical and mythological subjects. Without exploring his own taboo history, without at least the attempt to plunge in and then to camouflage it in part, Kiefer would hardly have achieved that memorable accord of fascination and aversion that occurs in some of his paintings with the "German theme," for instance in the marvellous panels entitled Deutschlands Geisteshelden (Germany's Spiritual Heroes) (1973, Eli Broad Family Foundation, Santa Monica) and Parsifal I/III/IV (1973, The Tate Gallery, London).

It irritates some viewers that Kiefer refrains from commenting, leaving the meaning up to each observer's interpretation. At the least, it seems questionable, therefore, to accuse the artist of transforming "the symbols of a faded and yet resonant national and military power into symbols of potential spiritual power,”[5] in order to adjust the "present" deficit of a genuine political power. Such an interpretation does not take into account that Kiefer approaches his historical and meta-historical subjects, be they Siegfried, Varus, Nero, Napoleon, or Hitler, with visible detachment and sarcasm. It is worth noting that the critic just quoted has admitted on another occasion that in the later pictures with mythological subjects such conscious detachment is very much in evidence: "Kiefer offers us a parody of creation and re-creation. This is most explicit perhaps in the various palette and book works, where the separation of these signs of art and thought from the canvas surface is either highly equivocal or, in the book works, sardonically exaggerated.”[6]

Undoubtedly, it is Kiefer's intent to reach an elevated spiritual level with his art However; he does not attempt this by glorifying its baggage as nineteenth-century history painters did, nor by a futile aspiration for changes outside art, but by approaching what the French philosopher Jacques Derrida has carefully circumscribed as "the experience of the unspeakable.”[7]

Books are warehouses of knowledge, useful yet almost incalculable; they are indeed where our historical and literary patrimony is stored, even if they "replace reality...with writing" and can contribute to the "weakening of authentic experience.”[8] Kiefer's books store pictures instead of words so that they may speak metaphorically They are, however, art objects first of all, more reminiscent of drawings and paintings than of printed volumes. For that reason, too, there are connections many books evolved from arrangements for early groups of works such as Bilderstreit II (Iconoclastic Controversy II) and Unternehmen "Seelowe" (Operation "Sea Lion"). Props like zinc bathtubs and clay palettes appear in both paintings and books in different settings and with different contents. The harmony between pictures and books concerns not only certain themes, but also the technical and painterly processes. In the case of the large books, whose form and weight remind one of the incunabula of Gutenberg's time, photographs printed on thickpaper are most often the basic material; but Kiefer also uses pieces of woodcuts, old canvas, and cardboard.

Books consisting of photographs are created in roughly three phases. At first the artist stages certain situations to be photographed. Then he enlarges the photographs in his darkroom. In the third and last step, the book is completed by painting over the photographs with chalk, oil paints, and bitumen, and from time to time adding sand, clay, hair, and lead. The multilayered process becomes part of the "final product" and can, so to speak, be reconstructed both mentally and pictorially.

Kiefer's books are made in the tradition of artist's books, which grew at the beginning of the twentieth century out of loose-leaf volumes, illustrated by painters and with a definite bibliophilic character. At the beginning of this development was the famous Vollard edition of Verlaine's Parollelement with lithographs by Pierre Bonnard, the appearance of which in 1900 is generally considered the birth of the artist's book.[9] A little later, thanks to the Dadaists and Surrealists, who illustrated and thus complemented literary texts, "the book as art object" continued to develop. This type of artist's book suspends the traditional connection between picture and text and almost completely eliminates the original semantic function. Even in production, traditional procedures had to give way to the artist's ideas. Typography was replaced by artistic concept; the product of a number of technical processes had become unique.

In 1977, Kiefer entered two works in the "Book" section of the exhibition "documents 6" in Kassel, and Rolf Dittmar wrote, "The book as a work of art becomes its own subject matter and as such an object in exhibitions which are no longer book exhibitions but art exhibitions"[10] Kiefer's loose-leaf books and book-objects have nothing in common with Bible illustrations by Chagall or Picasso's etchings for Ovid's Metamorphoses. There may be a distant relationship with the book collages of Max Ernst, such as La femme de 100 tetes (1929) and Une semaine de bonte (1934), in which he combined late-nineteenth-century woodcuts, mostly illustrations for adventure novels or other light fiction. However, while Ernst arranged the disparate material in visionary, absurd picture combinations so that the viewer's imagination can work unimpeded, Kiefer in his photograph books evokes historical memory, in order to direct the imagination toward the mythical.

Despite the genealogy of artist's books, Kiefer's works cannot be compared to others created in recent years; there is only a superficial similarity. The question here is neither the transformation of a book into a fetishistic object nor the illustration of a given text with pictures. Kiefer's books always have spines. He uses the sequence of the pages for the "conceptual" development of the theme implied in the title. In this way he can put into a different context and use for different statements related or even identical leaves, as he did in the books Nothung (Siegfried's Sword) and Die Donouquelle (The Source of the Danube). (In the latter he photographed his staging of the river's source.) The conceptual aspect of these early books is no longer a secret, but it seems to me that it has not been sufficiently investigated; there is a decided lack of essays on the subject. It appears that the impact of conceptual art at the end of the sixties was far more important for Kiefer than has so far been assumed.

This can be observed in Kiefer's painting as well, in which he often uses conceptual tricks to intensify the picture's effect and the tension between its different elements. For instance, in the painting entitled Varus (1976, Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven), the famous battle in 9 B.C. in the Teutoburg Forest is evoked only through the names of the two commanders, Varus and Hermann, and of nineteenth-century German writers and military historians who referred to this event. The picture is neither symbolic nor realistic; it is neither an allegory nor a history painting. Yet on the conceptual level—that is, on the intellectual and abstract level, where language (name) and stage (forest with blood spots) are joined—it boggles the imagination.

Kiefer's first books were created in 1969, when conceptual art had a great influence on the twenty-four-year-old painter. It would be wrong, however, merely to lump together books like Du bist Maler (You Are a Painter), Die Himmel (The Heavens), and Scherben (Shards) under a topical, if trendy, heading. These works were significant in the later development of Kiefer's work not only because of their method, but because of their content, in which the obsessive theme of the Third Reich is first announced. In 1975, the magazine Interfunktionen published eighteen photographs in which the artist appears in front of different backgrounds, saluting with raised arm. A short text explains: "During the summer and fall of 1969, I occupied Switzerland, France, and Italy" Since this is the Fascist salute, and since the "occupation" of Kussnacht, Bellinzona, Montpellier, Arles, Sete, Paestum, and Rome is implied, the photograph series clearly invites pertinent ideological interpretation. Kiefer, however, is interested in the artistic assimilation of historical material essential to him personally. He is, "in fact, an anti-hero, incapable of throwing off the chains of his countrymen and their memories" (Mark Rosenthal).[11] The theme of the fateful patrimony transformed into an inherited burden appeared as a leitmotif for the first time, and conspicuously, in Heroische Sinnbilder (Heroic Symbols).

If the one strand leading from Kiefer's early books can be termed conceptual, the other might be considered the sensual, pictorial component of his work. Examples can be found among the early pictures as well. One should keep in mind the two photograph books Nothung and Die Donouquelle (The Source of the Danube), in which a simulated source in Kiefer's dusty attic in Hornbach becomes the centerpiece of a pictorial "story" around which mythical fantasies and legends are wound. There is something romantic about the pictures, and although a veil of melancholy is pulled over the legends, the characteristic humor and the subtle irony with which Kiefer gets hold of his subjects come through.

A connection can be made with some works from the late eighties, for instance Spaltung I + II (Splitting l&II) (1987, Museum of Modern Art, New York) and Schweres Wasser (Heavy Water): books made of lead with photographs showing a staged cooling unit with radioactive rods; their point is existential—they raise questions about nuclear energy The miniature "portable reactor" with branding irons in boiling water symbolizes nuclear fission and the alchemical transmutation of elements: in these books Kiefer raises the tactile effect of the materials (lead, silver, red earth) until it becomes unbearable, so that the picture has not only a visual, but a pressing metaphysical, power.

“The book, imaginary library of history and stories, is expression of the ultimate faculty: not a metaphor for reality itself, but for its 'circumstances and 'depiction.' “[12] Keeping in mind the ideas of the philosopher Hans Blumenberg, whose book Die Lesbarkeit der Welt (The Readability of the World) has provided this essay with a title, one might take Anselm Kiefer's voluminous book production as an attempt to supply adequate pictorial metaphors for the description/assimilation of world/history.

Notes

1 Walter Grasskamp, "Anselm Kiefer." in Ursprung und Vision—Neu deutsche Malerei (Berlin: Frolich & Kaufmann. 1984), p. 33.

2 Ibid.

3 Manfred Frank. “Die Dichtung als Neue Mythologie (Poetry as the New Mythology) in Mythos und Moderne., Karl Heinz Bohre, ed. (Frankfurt:1983). p.19.

4 Mark Rosenthal, catalogue Anselm Kiefer (The Art Institute of Chicago. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1987).

5 Donald Kuspit, “Anselm Kiefer's Will to Power. Contemporonea I. no. 4 (November/December 1988). p. 52.

6 Ibid.

7 Jacques Derrida, Positionen (Vienna: Edition Passagen, 1986), p. 28ff.

8 Hans Blumenberg. Die Lesbarkeit der Welt (The Readability of the World)(Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1981), p. 17.

9 See Harriett Watts, Kommer in Das Buch des Kunstlers (The Artist's Book), catalogue of the Kestnen-Gesellschaft (Hannover 1989), p 51.

10 Rolf Dittmar, catalogue documenta 6 (Kassel: 1977). vol. p. 296ff.

11 Mark Rosenthal, catalogue Anselm Kiefer, p. 17.

12 Hans Blumenberg. Die Lesbarkeit der Welt, p. 140.