Kiefer's Wager: John Hutchinson

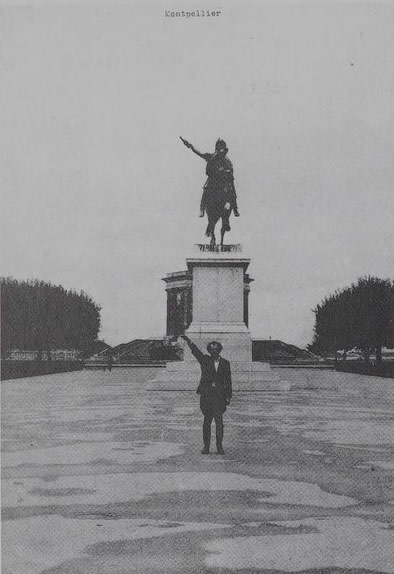

Anselm Kiefer. Besetzungen (Occupations), 1969.

Gradually, when the rooms house a selection of paintings and sculptures by Anselm Kiefer, the disused brick factory Kaiser & Böhrer in Höpfingen in the Odenwald will become a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). Not only the menacing-looking ovens, the massive wooden beams and the cavernous vaults are reminiscent of the artist's pictorial world, but also the building itself manifests his idea of elementary change and metamorphosis. Kiefer has already included the brickworks in his work, for example by taking a photo sequence of the interior of the factory in a publication about one of his most important recent works. Mesopotamia (1985/89)[1] These images are clearly defined and metaphorical at the same time. Viewed more soberly, the photographs show a place where bricks - the first artefacts of mankind - were once made. This peculiarity is essential. On the other hand, the transformative process of brick making, with the inclusion of earth, water, fire, air, has a symbolic dimension of elementary wholeness, which is just as important. In addition, the correlation of the brick factory with "Mesopotamia" is highly symbolic.

Let's look at some of the issues related to this. Mesopotamia, the southern part of Babylon, a flat alluvial plain bordered by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers with the city of Nineveh as the site of the important library of antiquity, is handed down to us as a source of Western culture. Almost everything we know today about the highly developed Babylonian culture was recorded there on clay tablets, the common building material was mud that was dried into bricks in the sun. The rivers coming down from the plateau of Armenia left abundant morass in that alluvion, and through intensive artificial irrigation the Babylonians were able to cultivate large areas on both sides of the river. But Mesopotamia was also the land of the Flood. And the disintegration of Babylonia was followed by centuries of fallowness. This resulted in the drying up of the once fertile land. All this is history.

It is precisely this "falling into disgrace" that has been handed down in the myths. Mesopotamia is considered the Garden of Eden, where, according to the story of creation, Adam was created from the "dust of the earth". At the end of the Bible, in Revelation, John tells of his vision of a woman sitting on a scarlet beast "described all over with blasphemous names". On her forehead was a name, a mysterious name: BABYLON THE GREAT, MOTHER OF HARLOTS AND ALL THE ABOMINATIONS OF THE EARTH," he says. After that, I saw another angel descending from heaven; he had great power, and the earth shone with his glory. And he cried out with a mighty voice: fallen is Babylon the Great! It has become the dwelling place of demons, the dwelling place of all unclean spirits, and the abode of all unclean and abominable birds." If you add this meaning, "Mesopotamia" symbolizes the beginning and end of history and myth. The brick factory, full of Kiefer's allegorical art, will stand for this cycle and its possibility of transcendence.

The process of transformation is never complete in Kiefer's art. Accordingly, his ideas of change and restoration have been constantly modified over the last twenty years, and the state of equilibrium, the hidden goal of his artistic work, has become more and more decisive. Initially, Kiefer concentrated on German history, but today he deals with world history.

Nevertheless, these two interests are not mutually exclusive, on the contrary, they are intertwined. Kiefer's art leads us to new insights, namely that the transformation of German history cannot come about separately from that of world history and that neither of them can be achieved without individual freedom.

Occupations (1969, ill.), a series of photographs showing the artist in the new staging of the Nazi salute, frees a symbol of German fascism from the significance of oppression and shows it on a world stage. In The Flood of Heidelberg (1969), Kiefer juxtaposes depictions of architecture in the Third Reich with his own studio photos. In Every Man Stands Beneath His Celestial Sphere (1970), a saluting figure - perhaps the artist himself - sees beneath a transparent hemisphere that hints at constriction and the need for liberation. Gradually, the artist's presence is withdrawn from the paintings. In many paintings created in the seventies, including Märkische Heide (1974) and Varuss (1976), we find paths and traces that symbolize impersonal search and dynamic change. Recently, this impersonal path of transformation has been internalized: it can be found today in the wisdom of the lead books of "Mesopotamia" or in the mysterious metaphysics of Kabbalistic symbols.

Whereas in the past his excavation of the Nazi past caused controversy, today it is above all the gigantic nature of Kiefer's reproach, which is expressed in his extensive work, that provokes.

Although he makes no claim to extravagance in his art, there is no doubt about the absoluteness of his work. The early work, with its homeopathic attempt to liberate Germany from its Nazi legacy, may no longer seem as combative as it once was, but Kiefer's contemporary art is still judged by some critics to be megalomaniac and ideologically reactionary. This is perhaps less surprising than it may seem, since postmodern ambiguity is a defining aspect of Kiefer's strategy. His symbols are ambiguous, his allegories are often contradictory, his seriousness and the high spirit of him are usually ironic. Even Kiefer's ambiguity is characteristic. The ambivalence in his paintings draws our attention to the change of meanings in contemporary Western culture, but it also draws us to the unspeakable nature of reality. Meanings blur, merge into each other and dwindle - as does the physical presence of paint, photos, ashes, straw and lead. And even this disappearance ultimately serves a higher purpose, a vision that would make all fragments one again.

Many of Kiefer's paintings have to do with erasure, and here he seems to reflect the desperation of many works of postmodern art. However, the Kiefer emptiness - burnt fields, wastelands, clay pits - is a beginning, not an end. There are plenty of clues pointing in this direction. Assuming that this metaphysical ambiguity is the basis of Kiefer's work, one can see his paintings in the light of modern idealism. Basically, Kiefer's iconography suggests that matter is nothing but a transitional stage in a process towards complete spirituality. In contrast to the paintings of Mondrian or Malevich, whose non-objective = emptiness can be understood as an absolute Plenum after a short pause, Kiefer's pictures are not so readily accessible. Frequently recurring inscriptions contained in the image undermine the immediacy of visual representation And one can never escape the historical peculiarity. Seen in a system, Kiefer's art tries to lead us through the forecourt of recent history with the help of myth, towards questions of being. In other words, the only way to achieve a spiritual vision is through the world. Until the reality is fully transformed, the kingdom of God cannot come.

But if today, after twenty years, there is no doubt about Kiefer's artistic potency with which he presents us with his visions of transformation, can we assume that they are more than just chimeras?

Kiefer's investigations of German history and culture must be juxtaposed with a very different social background of guilt and oppression. The period between the end of World War 2 and Adenauer's accession to power in 1949 - known as the "white years" of German history - was remarkable, because of two gaps in the national consciousness. The first void was created by a lack of community spirit, since after the bombardment of German cities and the unconditional surrender of the German army, the Volksgemeinschaft - the core of Nazi ideology and propaganda - was replaced by striving for individual, self-interest. This phenomenon, in turn, was part of an even greater vacuum, a kind of national amnesia, a suppression of the immediate past. It was not only the individuals - both men and women - who refused to accept and to recall the atrocities of the Third Reich - no, it was just as if they had been deprived of the ideology, the substance of that past. And since this ideology had not been atoned for, but only repressed, it continued to haunt the national consciousness of the Federal Republic of Germany for at least 20 years. Long after German cinema and the new savages had begun to ask questions about German identity and the fascist past, the 1986 Historical Controversy—a debate among historians about those things—took the issue to the extreme. In the Historikerstreit, some right-wing historians tried to "normalize" German history by relativizing the "Final Solution." A shift to the right in German politics was at the root of the whole debate, and various splinter groups were determined to purge Germany's past in favor of a reactionary ideological approach in search of a "usable past. This reappraisal of German history, originally a project of the left, was thus partially usurped by the right-wing auditors.

Kiefer's revival of fascist iconography caused many of his German comrades to turn away in disgust, especially because his striving for historical "transformation" could also be interpreted as conservative revisionism. This, too, was probably unavoidable, as Andreas Huyssen has observed.[3]

“With what seems to be an incredible naïveté and insouciance, Kiefer is drawn time and again to those icons, motifs, themes of the German cultural and political tradition which, a generation earlier, had energized the fascist cultural synthesis that resulted in the worst disaster of German history. Kiefer provocatively reenacts the Hitler salute in one of his earliest photo works; he turns to the myth of the Nibelungen, which in its medieval and Wagnerian versions has always functioned as a cultural prop of German militarism; he revives the tree and forest mythology so dear to the heart of German nationalism; he indulges in reverential gestures toward Hitler's ultimate culture hero, Richard Wagner; and he suggests a pantheon of German luminaries in philosophy, art, literature, and the military, including Fichte, Klopstock, Clausewitz, and Heidegger, most of whom have been tainted with the sins of German nationalism and certainly put to good use by the Nazi propaganda machine; he reenacts the Nazi book burnings; he paints Albert Speer's megalomaniac architectural structures as ruins and allegories of power; he conjures up historical spaces loaded with the history of German-Prussian nationalism and fascist chauvinism such as Nuremberg, the Mairkische Heide, or the Teuteburg forest, and he creates allegories of some of Hitler's major military ventures.”

The controversy would have been much less serious if Kiefer's art had explicitly condemned Germany's fascist past. Although - and precisely because - his iconography is broken by irony and dismemberment, his paintings always seem ambiguous, sometimes even elegiac. Thus, many critics have doubted the integrity of his strategy. Other authors, including Donald Kuspit, have supported him. "Kiefer eliminates the arrogant structures (peculiar to the German psyche) by decomposing them, by turning them against themselves, so that a new beginning can be made in the sense of creating a new human self," he wrote in 1984.[4] Nevertheless, Kuspit also expresses a number of reservations. “Kiefer is extremely tangled," he continues. "His art is an exhibitionist demonstration of artistic power in the name of general humanity and German strength, in the name of unique German unity."[5]

Benjamin Buchloh, who has long been an opponent of Kiefer's ideals, criticizes him from a similar point of view. “Anselm Kiefer is merely the most famous of the German artists who consider those concepts that Liaberman described as 'traditional identity' to be modeled, he notes. "In the process of restoring those concepts, these artists have created a type of work that is now widespread and has its own impact in North America as well—and can at best be described as political kitsch.

Its attraction seems to lie not only in the restoration of traditional identity for generations of West Germans who prefer to leave out the long and difficult process of considering a post-traditional identity would prefer to skip it. The attraction of political kitsch seems to be - and this is where its international appeal lies - is the restoration of artistic privilege combined with traditional identity, as well as the claim to have privileged access to ‘see’ and 'represent' history[6].” But is Kiefer really trying "traditional identity? How to find it? Even a superficial examination of his work reveals that Kiefer symbolically depicts history: His paintings are based on historical narratives only insofar as he alludes to the necessity of their transformation. He does this by blurring the distinctions between history and myth. Andreas Huyssen acknowledges this, but argues that Kiefer is incapable of triggering the transformation he is concerned with. "Kiefer's work gave rise to that mystification that says that myth transcends history in a certain way, that it can redeem us from history, and that art - especially painting - is the golden path to that redemption," Proceeding from the premise that this promise of redemption is what undermines Kiefer's status as a contemporary "Master", he concludes that the artist's flight from history into myth is a tacit concession of a deficit, albeit a tragic one. In it, Huyssen comes close to Kuspit’s and Buchloh's skepticism, but does not accuse Kiefer of insincerity. Huyssen does not doubt the fact that Kiefer's search is a form of transformation, which he perceives as a deliberate repetition of cultural oppression. "The issue," he says, "is not whether one should forget or remember, but rather how one remembers and how one can deal with images of the remembered past. Most of us, more than forty years after your war, only know this past from pictures, films, photos and representations. I see Kiefer's strength in his way of dealing with this problem aesthetically and politically, a strength that must make him at the same time and inevitably controversial and extremely problematic."

According to Huyssen, the problematic nature of Kiefer's pictorial world lies in its lack of "any clear reference to contemporary reality" and especially in its current focus on alchemical, biblical and Jewish themes. He adds: "Kiefer's very own treatment of fascist images seems to extend from satire and irony in the seventies to melancholy devoid of any irony in the early eighties. Works such as The Staircase (1982/83) and Interior (1981) exude an overwhelming, inescapable compulsion, a monumental melancholy and a fierce aesthetic attraction that exerts something highly meditative, if not paralyzing, on the viewer. According to Huyssen, Kiefer's work is imbued partly with his self-questioning and his painterly self-confidence, and partly with the feeling of mourning that he expressed in Margarete (1981) where it "evokes the terror to which the Germans exposed their victims". His best works, such as Icarus—Märkischer Sand (1981) "draw their strength from the often unbearable tension between the terror of history and the infinite longing to go beyond it through myth". But this vision only gives rise to the hope of salvation, only to be excluded from it.

The assertion that there is no melancholy in Kiefer's art is in itself ambiguous. Although Kiefer's subliminal admission of weakness is a kind of strength in Huyssen's eyes, he seems to regard his simultaneously highly meditative state of consciousness as a form of entropy, akin to the melancholic "Überciruß" in Dürer's Melancholia. But the emphasis on this issue may have more to do with Huyssen’s than with Kiefer's worldview. A humorous relationship with the obvious impossibility. One of his projects - the leaden plane cannot bend, the Icarus/artist is doomed to fall - emphasizes the radical nature of the alternative proposed by Kiefer as much as it signals his hopelessness. A bleak work such as Ways of Worldly Wisdom, the Battle of Hermann (1980) can be regarded as a conception non-worldly wisdom can provide us with answers; likewise, one could also understand it as a hymn of praise to nihilism or a homage to the glorious German metaphysics. Kiefer's allegories always remain open. The fact that he refers to the cultural in his work — sometimes clearly, sometimes hinted at — gives rise to quite controversial interpretations.[7] Therefore, the attempt to resolve conflicts of interpretation is less appropriate than that of creating a framework of pre-understanding for the questions contained in Kiefer's paintings. Of course, such a framework does not raise questions of ideology because, as Paul Ricoeur has argued, all hermeneutics transmits a "surplus" of meaning according to its own "key" framework of relations, but the detours of language, myth, ideology and the unconscious must be explored before there can be an encounter with questions of being and non-being. History precedes me and my contemplation," writes Ricoeur.[8] One cannot engage in any hermeneutics of "assertion" before faith has undergone a cultural critique, a hermeneutic of "mistrust".

It is obvious that Kiefer's depictions of German history amount to a certain extent to a "suspicious" cultural critique. And so, according to Ricoeur, it can be concluded that the ambiguity of his symbolism has a definite purpose. According to Richard Kearney: "Just as something that cannot be possessed, cannot be reconquered, cannot be anticipated, (Ricoeur's) eschatology of the sacred remains the most apt example of the risk of interpretation. In contrast to the teachings of mostly traditional metaphysics, no triumphant ontology is tolerated here that could break out of the hermetic of interpretation. On the contrary, every effort is being made to create what Ricoeur calls a 'militant and mutilated ontology' which plunges us ever more violently into an internal struggle of conflicting interpretations. Here, absolute renunciation of what one self-righteously assumes to be safe is demanded.[9]

If Kuspit and Buchloh are right, Kiefer conveys an inkling of sacred or spiritual power by reviving old myths of the Germans. So he falls victim to reactionary idealism. But as much as his ironic depiction of myths and cultural icons demonstrate their non-existence in the ontological sense by revealing their immaterial presence, his paintings have nothing at all to do with re-evoking. As Doreet LeVitte Harten noted, "Kiefer does not want to and cannot offer a perfect solution, but he can point out its importance and necessity."[10] In reference to this, Kiefer cites the symbolic power of mythology while at the same time dismantling individual myths. LeVitte Harten also explains that Kiefer assembles mythological fragments in such a way that they are "reminiscent of the analytical method of the Levi-Strauss If we compare the images with the structures of the myths, we discover that each work, as well as the myths, contains different layers or interlocking systems of a visual and conceptual nature, geological structures or psychologicaly similar to analytical studies... The levels support each other, cancel each other out, explain each other, and in doing so, they reduce history to mere abstraction." From this she concludes: "By defining Kiefer as a myth-maker and not as a myth-teller, we put him on a par with a bricoleur as described by Levi-Strauss, who changes the context of things so that they function differently in their new role or in a new design." LeVitte Harten reveals a certain way in which Kiefer's work "transforms history". If his pictures function as contemporary myths in the sense of Levi-Strauss, they can evoke profound changes - even if on an intellectual basis.

The idea that Kiefer, like a bricoleur or shaman, creates new myths is reminiscent of the influence of Joseph Beuys on an entire generation of German artists, among them Kiefer.

With his art, Beuys explicitly wanted to move society to a deeper understanding of itself and its problems. While emphasizing parallels between the nature of the material world and the interior of man, he believed that any radical revolution was possible only through self-transformation. For Beuys, the way to solving the problems of the world and to freedom lay not in materialism, but in the transformative power of ritualized thoughts and actions: he assumed that there was a connection between man and the rhythms of the cosmos. The artist — and Beuys represented the view that each of us has the capacity to be an "artist" in his or her own sphere of life must create ambiguity between what is usually regarded as the "real" and the "unreal." If one accepts a shaman-like channel between "matter" and "spirit", artistic transformation will not be limited to the intellectual. At the very least, art sets in motion a psychological change on the conscious and unconscious level of thought. But despite many points of contact with Beuys' work, Kiefer's paintings are not built in the same way. And as LeVitte Harten has noted, "(Beuys) focused more on survival rituals than on paths to redemption... (He) never ventured outside the safety framework of his worldview, which remained mythological until the end of his life." Kiefer, on the other hand, finds strength in uncertainty.

By referring to the alchemical elements in paintings such as Athanor (1983/84) and Nigredo (1984), Kiefer conveys to us that transformation must ultimately take physical form. Although not overt, alchemy also contains a psychic dimension. "The alchemical process of the classical period (from antiquity to about the middle of the 17th century) was an intrinsically chemical investigation in which unconscious psychic material was mixed by way of projection," wrote C. G. Jung. "The psychological condition of the work is therefore often emphasized in the texts. The contents under consideration are those that are suitable for projection into the unknown chemical substance. Because of the impersonal, purely material nature of the material, projections of impersonal, collective archetypes take place. In parallel with the collective intellectual life of those centuries, it is mainly the image of the spirit trapped in the darkness of the world, that is, the unredemption of a state of relative unconsciousness that is perceived as embarrassing, which is recognized in the mirror of the material and therefore also treated in the material.[11]

Jung was criticized for being more concerned with the "psychic transformations" induced by alchemy than with their chemical properties. Kiefer, on the other hand, tends to emphasize the physical side of change through alchemy, which can be seen in many of the paintings in which nigredo — the blackening by the burning effect of fire — is recreated on the canvas. It is not insignificant that Kiefer's interest in alchemy, which emerged in the mid-eighties, also meant a shift in the preoccupation with the self — with the artist as shaman — towards emphasis a rather impersonal form of power. At the same time, the idea of art as the only means of cultural transformation was dropped.

This new direction recalls Jung's conviction that alchemy has much in common with the psychoanalytic process of "individuation," in which "by renouncing the earthly goals of the ego and accepting what is coming, the individual feels attached to something that lies beyond the ego, something that lives in himself and through him.[12] Individuation, usually beginning in midlife, is evoked by the self-regulating principle in consciousness, in which the animus (the active, male, "intellectual" drive) is predominant. Frequently, this is combined with the emergence of unsolvable conflicts that can only be "resolved" by separating from a set of feelings and attaining a new level of consciousness. This separation is associated with the subordination of subjectivity to a higher goal. The Jungians used the Osiris myth, which Kiefer dealt with, as a symbol of this process. Osiris, whose kingdom was in Egypt (according to Jung, the first half of his life is determined by the mythology of the hero), is killed, after his resurrection to life, he decides to rule the Egyptian realm of the dead instead of returning to earth. This decision marks a turning point in life at which man decides to renounce his position of power.

"Individuation" as a way of regaining psychic balance, which usually contains a harmony with the anima, or the feminine, "feeling" principle. This process is not without danger, as Gaston Bachelard noted. "The psychology of the alchemist is that of dreams, which seek to realize themselves through experiments in the outer world. Alchemical gold is the objectivity of a "strange desire for kingship, superiority and domination, which incites the animus of the lone alchemist ... The dreamer does not need gold for his former social advancement, but immediately for an immediate psychological purpose: to be ruler in the sublime splendour of his animus.”[13] This repeats, just putting it differently, Kuspit and Buchloh's misgivings about the megalomania they think they find in Kiefer's work. Jung himself elaborates on this in a similar way. During individuation, there is a risk of losing balance, or not reaching the conscious, and of inflating consciousness. An inflated consciousness is always self-centered and only conscious of its own presence... It is therefore dependent on disasters that kill it if necessary. Inflation is, paradoxically, an unconsciousness of consciousness. This case occurs when the latter takes over the contents of the unconscious and loses the ability to differentiate, this condition sine qua non of all consciousness.[14]

"Inflatedness," it seems, belongs to the same category as the "predominance of melancholy" that Huyssen senses in Kiefer's art. Jung cites Faust and Nietzsche as examples of individuals who collided with "pomposity"... He could also have mentioned Hitler.

The High Priestess, English title of the sculpture Mesopotamia (1985/89), is an archetypal symbol of the "wise" aspect of the "anima". This may mean that we should accept the anima within us and entrust ourselves to its intuitive wisdom. In this context, it is important that "Mesopotamia", an ensemble of leaden folios, was created from a material that is in itself durable and chemically unchangeable. Lead is toxic and heavy; It is used with Saturn is associated with melancholic humor, and in Jewish Kabbalah, lead is the primordial substance par excellence. In Mesopotamia, the lead keeps the clay applied to many pages of the book in balance. (An accompanying series of photographs from the studio in which Mesopotamia was created is juxtaposed with the photos of the brick factory).[15] We are confronted with a source of impersonal — or suprapersonal — wisdom that contains appropriate knowledge or banishes the "ability to distinguish" in Jung's sense and thus the danger of "inflation (inflatedness)". Although it is difficult to access this knowledge, it is still literally accessible, as if in a figurative sense. Most of the books contain photographs — in different ways — that depict comprehensive "reality": they show scenes in Germany and the Middle East, railroad tracks in Chicago and skyscrapers in São Paulo. However, the impression of "reality" is destroyed by etching and painting over the photographs, so that the images gradually evoke associations of decomposition and dissolution. Together with images of clouds and water, this results in an effect that is reminiscent of nuclear energy. All four elements are symbolically represented. Today, when we engage with Zweistromland / The High Priestess, we are led back through time, as if past and present were experienced simultaneously in the sense of a synchronic history. The most disturbing elements within the pages of the book are a few tufts of black hair that are deadly psycho-sexually charged. They are allusions to Shulamith, the Jewess in Paul Celan's poem Death Fugue, which inspired Kiefer to create a series of paintings. Apart from some fragments of nipples taken from a magazine, hair is the only figurative element within the lead books.[16]

Kiefer's interest in Shulamith and Jewish history is also evident in other new works. That is certain. First of all, the fate of the Jewish people — and especially the Holocaust — is inextricably linked to German history. And then alchemy and Jewish mysticism have some ideas in common. For example, Gershom Schalem, when he writes about Kabbalah, says that "only when the soul has got rid of all boundaries and, symbolically speaking, has descended into the depths of nothingness, does it encounter the divine.”[17] This is a clear parallel with the process of burning out the alchemical nigredo. Referring to later Kabbalistic thoughts, Schalem writes: "Salvation could not be obtained by rushing forward in an attempt to hasten historical crises and catastrophes, but by tracing back the path that leads us to the primordial beginnings of creation and revelation, to the point where the origin of the world (the history of the universe and the history of God) began to develop within the framework of a system of laws.”[18] It is precisely at this initial point that Kiefer's nihilism is confirmed.

Kabbalistic doctrine is notoriously obscure, but the core of its message is that everything proceeds from God; there is no such thing as "creation" in the usual sense. Nor is there such a thing as eternal "matter": the "created" world was brought about by God's self-unfolding. Kabbalah teaches the fundamental identity of all things with the Absolute, and not only matter and spirit are equal in their innermost essence. Thus, what we perceive as the substance emanating from true reality is mere nothingness and illusion that appears and disappears like a fleeting shadow. "The will of the Absolute is realized in the power of consciousness moving downwards through the worlds, in order to expand completely in dense matter. Here is the turning point — it returns in ever-growing levels of consciousness, in metals, minerals, primitive and higher plant species, lower and higher living beings.[19] Kiefer refers in pictures such as Emanation (1984/86) and Untitled, (1980/86) and the doctrine of Tsimtsum — the process of concentration and contraction, the core of Kabbalistic "creation thought" — is linked to the idea of the "breaking of vessels," which explains the existence of evil in the world. According to this myth, the rays of the divine light, which fell into the original space of the tsimtsum, were to be captured in special vessels. But for six of the nine shells, the load was too great. When they broke, evil, demonic forces escaped from them and set in motion the multi-layered cosmological drama. The counterpart to this myth is the idea of Tikkum, the restoration of the vessels. Tikkum wants to restore unity to the name of God, which was destroyed when the vessels shattered (the medieval Kabbalist Isaac Luria speaks of the letters 'JH’, the name YHWH, or Yahweh, which were separated from the letters ‘WH’. The characters JH written on the iron skis in Kiefer's painting Jerusalem (1986) are probably not appropriate.[20]

In Kabbalah, therefore, we find an exact system of transformation, in which this very creative power is first destroyed, but then the process is reversed. This idea of the nature of the world is reflected in Kiefer's recent works.[21] However, the artist never used this to explain his work; He follows the alchemical principle of obscurum per obscuris, ignotum per ignotius. The viewer must recognize the kawwana (mystical content) that characterizes Kiefer's concern — and then accept or reject it.

Even in connection with Kabbalah and Hermetic literature, Kiefer does not abandon the historically characteristic. A clue to the way in which he combines these two things can be found in the following observation "Isaac Luria's Kabbalah," he writes, can be described as a mystical interpretation of exile and redemption, or even as the great myth of exile.[22] Kiefer added a photographic essay to the catalogue of his American retrospectives[23] entitled "Passage through the Red Sea", preceded by a prologue in which he seems to suggest that his work could be interpreted as a call to return to the promised land. Images such as Exodus from Egypt (1984) point to something similar. And because these images of exile and redemption are meaningful to all of us, they carry Judaism back to the core of contemporary German culture. Kiefer attempts to repair a "broken vessel" by reassembling fragmented elements of German history. He mourns the Holocaust, as in Your Ashen Hair, Shulamith (1981), but at the same time he celebrates the resurrection of Judaism.

In connection with the "reparation of history" that influenced Kiefer's early work, there is another essential aspect. In this century, the German Culture has a problematic relationship to the idea of the "spirit". The German people had long prided themselves on being a spiritual nation. However, the claims made in the name of sacred German music and the philosophical and ideological brilliance of German literature have often been occupied by right-wing nationalism — and most devastatingly by Nazism. The political ambivalence of German metaphysics in the twentieth century is vividly illustrated in the development of the philosophy of Martin Heidegger, whose thought in the thirties made that notorious "turn" from the phenomenology of human existence to a phenomenology of language that subordinated the human being to the idea of "being". According to Heidegger, the relationship between the thinking subject and the imagined object—which initially exists without intention or rational choice—cannot comprehensively describe our habitual relationship to things. He assumes that our conscious reflexive thinking is normally limited to situations in which we lack deeper knowledge of theoretical and scientific facts and questions of being. Not engaging in such reflections, he argues, is a form of existential "non-authenticity," according to some commentators, this "turn" occurred when he introduced a historical dimension to this system of things. If all "meaning" lies in our existence ("being-in-the-world"), and if contemporary culture is determined by a terminology without standards of value, as Heidegger believed, it follows that it acquires no "meaning". This adherence led to his short-lived but catastrophic partisanship of National Socialism as the political system that would give cultural terminology its rightful place again, paving the way for the "question of the essence of being."

In Being and Time, written in 1927, Heidegger states that it is necessary to separate the concept of spirit as an essential element of traditional philosophical vocabulary. Thirty years later, he praised the poet Georg Trakl for having successfully avoided this word. However, Jacques Derrida reveals in a recent study[24] that during these years, and especially in 1933-35, Heidegger had used the word intellectually constantly and in a positive sense. By showing that Heidegger's "derailment" occurred at the very moment when his political convictions were most suspicious, Derrida arrives at a general realization. There is a close connection, according to Derrida, between the philosophical vocabulary of "being" and political delusion. Derrida also notes that Heidegger does not refer at any point to the Hebrew word for "spirit," Ruach, possibly because of his insistent opinion that "real" philosophy was written exclusively in Greek and German. For Derrida, this is closely linked to Heidegger's etymological stance and his political convictions.

Heidegger's "forgetting" of Ruach can be seen as symptomatic of the blind oppression — and attempted annihilation — of the Jewish people during the Third Reich. Kiefer's passion for Jewish history and spirituality shows his longing to make amends for this offense. This longing also testifies to the desire for the right to examine questions of "spirit" and "being" independently of guilt. Kiefer wants to transform the serpent of evil into the staff of salvation. His bet is that the miracle is possible.

Notes

1 These photographs have been reproduced in Zweistromland, DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1989.

2 J. P. Stern, Germans and the German Past, in London Review of Books, vol. 11, no. 24, pp. 7-9.

3 Andreas Huyssen, Anselm Kiefer: The Terror of History, The Temptation of Myth, in October, no. 48, pp. 25-45. These and all other references to Huyssen were taken from this excellent essay.

4 Donald Kuspit, Transmuting Externalization in Anselm Kiefer, in Arts Magazine, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 84-86.

5 In a recent essay, Anselm Kiefer's Will to Power, in Contemporanea, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 50-57, Kuspit accuses Kiefer of neo-fascism, "The collective Nazi past is the narcissistic core of Kiefer's own identity; his main sense of self is that of the heir to the Nazi past." Among other extraordinary remarks, he assumes that "Kiefer is a successful artist and a would-be ruler / tyrant.

6 Benjamin Buchloh, A Note on Gerhard Richter’s October 18, 1977, in October, No. 48, p. 100.

7 Kiefer's symbolism has been interpreted differently by critics. In a conversation with the author, the artist himself emphasized that his symbols could not be clearly deciphered.

8 Paul Ricoeur, Hermeneutics and the Human Sciences, cited in Richard Kearney, Modern Movements in European Philosophy, Manchester 1986, p. 99.

9 Kearny, p. 107.

10 Doreet LeVitte Harten, Anselm Kiefer, in NIKE, No. 29, pp. 18-19. All other references in connection with Doreet LeVitte Harten were taken from this essay.

11 C. G. Jung, Psychololgie und Alchemie, Walter-Verlag, Olten 1975, p. 542.

12 Anthony Storr, Jung, London 1973, p. 88.

13 Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Reverie, Boston 1971, pp. 72-73.

14 Jung, cit. (see note 11), p. 547.

15 Mesopotamia (see note 1).

16 Mark Rosenthal writes in his comprehensive essay in the catalogue on the occasion of the Kiefer retrospective (The Art Institute of Chicago, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, Museum of Modern Art New York 1987/88): "Kiefer's interest in the central themes of the Byzantine iconoclasm had already been evident in his art since 1973, when he only named the persons of the Trinity, instead of depicting them. This is reminiscent of the medieval debate as to whether painter-monks were allowed to depict Christian figures. The Byzantines believed that the images were more than mere representations—they believed that the images were the emanation of the deity himself. That is why the worship of images was associated with magic" (p. 76). This thought, combined with the Jewish ban on idols, may be an explanation for the absence of persons in Kiefer's more recent works.

17 Gershom G. Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, New York, 1961, p. 25.

18 Ibid., p. 245.

19 Z'ev ben Shimon Halevi, Kabbalah and Psychology, Bath 1986, p. 15.

20 Mark Rosenthal, op. cit., p. 160 (see note 16) notes that the initials JH, engraved on the metal skis, stand for the name of the craftsman who made them. This could be the most likely explanation for the existence of letters.

21 As mentioned above, Kiefer is interested in the idea of art as "emanation": his paintings can be seen as microcosmic forms of the Kabbalist process of transformation: consciousness is formed in matter and is returned to its origin by means of Kawwana.

22 Scholem, op. cit. (see note 17), p. 286.

23 Anselm Kiefer, The Art Institute of Chicago and Philadelphia Museum of Modern Art, 1987.

24 Jacques Derrida, Of Spirit, Chicago 1989.