Anselm Kiefer Whipping Boy with Clipped Wings: Peter Winter

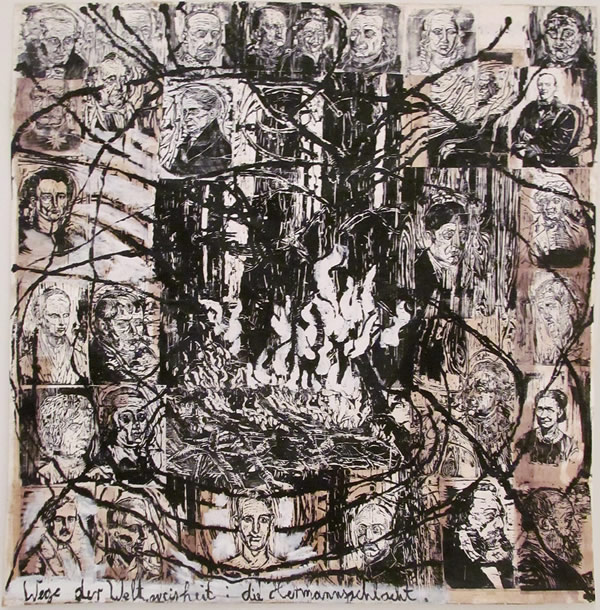

Anselm Kiefer. The Ways of Worldly Wisdom, 1976-77.

West German art critics tend to asume that Anselm Kiefer is a nationalist painter. This assumption has more to do with an easily identified taboo than with the content of the work itself. Kiefer's painting is cited as a dubious example of home-grown art, distinguished by an uncritical penchant for Teutonic sagas and barbaric epics. According to German critics, the paintings create an atmosphere in which the primitive wrestling ring is confounded with the sacrificial altar. How, they protest can one paint like this in the twentieth century?

Short of banning him, the domestic critics would like at least to tell Kiefer what he ought to paint. Kiefer, they say, has burnt his fingers more than enough, for example in his Painting of the Scorched Earth, in To Paint=To Burn and in the book, The Cauterization of the Rural District of Buchan. To date, no one has publicly invited him to burn his pictures (though he occasionally does precisely this as part of his painting): recent commemorative exhibitions in Germany concerning the Nazi book and picture burnings of 1937 have made people think twice about that sort of thing. Attitudes towards Kiefer divide as they do towards Georg Baselitz, A.R. Penck, Markus Lupertz and Jorg Immendorff. There are hostile critics for whom historical themes will always be considered as illustrations, playing the same role in painting as in childrens’ textbooks. For these people, the fact that Immendorff once taught drawing at school is sufficient proof of his didactic orientation.

Such an understanding of narrative in contemporary art, and in Anselm Kiefer's pictures in particular, is palpably simplistic. The surface of every good painting. especially one by Kiefer, is like the false bottom of a capacious trunk. His familiar, thick imposto is better at hiding than at delivering up concepts or images. The difficulty is double, since the many portentous titles usually send one off in the wrong direction. Kiefer is neither a historian nor sociologist even less a psychoanalyst of collective guilt repression. He is, simply, a painter—a painterly painter.

Shortly after the opening of the 1980 Venice Biennale. the journalist Wolf Schon expressed feelings shared by many others upon seeing Kiefer in such a prestigious setting:

This Biennale has adopted another slogan from the sixties, which is "Regionalism." Long live the provinces!—after decades of being smothered by fine arts Internationalism and its "Anything and Everything" philosophy. The Germans have responded to this new loosening up with a veritable provocation... Working on a format the size of a wall, Anselm Kiefer has turned the tanning bark of old Germania into the beams and planks of an ancient war council room or Valhalla. Inside dwell Robert Musil and Thomas Mann, Theodor Storm, Nikolaus Lenau and Adalbert Stifter, but also Joseph Beuys—Germany's Spiritual Heroes, according to the title of this primitive and uncouth Teutonic image, with its obsessive perspective. Its counterpart is entitled Parsifal. By the chalice of wine is a dedication—"to the marvel of supreme redemption, redemption to the redeemer." Is this neo-Nazi Blood-and-Soil art, a relapse into the "glorious past"—as the Neue Zurcher newspaper recently termed it?... When the nationalist feeling threatens to become overly sentimental, the artist reacts by taking out a burin and making rows of crude and unrecognisable woodcuts of great German intellectuals. In spite of this, the title of the work—nine woodcuts, one square metre each—is supposed to be taken seriously: The Ways of Worldly Wisdom—the Battle of Arminius. Next one comes across the charcoal- and dirt-covered pages of a ludicrous photo album which has been "scorched." "submerged" and "covered with silt." In one work, the rich soil of the Homeland steams and smokes. In yet another, the battle for England is acted out in an ice-covered bathtub. Further along, the sands of the Brandenburg March awaken memories of Prussian tradition. [1]

Kiefer's interest in historical themes is married to a taste for monochrome nuance, for subtle greys. for the texture of the image. In fairness, his art has more to do with Tachism than with fascism, despite critical opinion to the contrary. The choice of materials, more typical of a sculptor than a painter (especially in the most recent period), is notably similar to that of Kiefer's former teacher Joseph Beuys. Kiefer's use of molten lead, the way he scorches and chars parts of his pictures with a blow torch, and the alchemical manipulation of asphalt, shellac, sand and straw all bring Beuys' example to mind. "History for me," says Kiefer, " is a material, like landscape or like colour." One thinks also of the dramatic manner in which both artists approach composition. It is as if they were preparing for a battle, with ships in the bathtub and topographical sketches of the land nearby, with photographed sand models used as the painterly background or transformed into the thick pages of books. Such motifs

suggest Kiefer's affinities with action art. In fact, he has very little in common with the Neo-Expressionism of Berlin and Cologne, with which he is frequently associated. The spontaneous and direct effect of his painting results from a careful, professional preparation and from an almost Prussian rigour. For that reason, his production is limited, and relatively few paintings come out of his factory-like studio in Buchen.

The critic Eduard Beaucamp wrote the following about Kiefer's 1984 solo show that travelled from Düsseldorf to Paris and Jerusalem:

One could call him an intellectual and painterly charcoal-burner, since his subjects always include forest, wood, fire and flame and because the central visual motifs are burning, scorching and charring. Kiefer's defenders are quick to cite the example of German Romantic painters and of fairy tales: they quote Wagner and Heidegger. Kiefer is in fact a breaker of taboos. He seems to possess a magic power to upset by calling up forbidden national myths and legends and by giving voice, albeit in a whisper, to the destroyed dreams of heroes, of wars, of cults, of lost history and landscape, of grandeur and frenzy... In a childlike script that reminds one of Beuys. Kiefer jots down a title, a theme or a thematic association on the body of the painting, the giant images of which act like a soundbox to the words... The exhibitions of the last ten years have revealed a remarkable fruitfulness. Kiefer would like to return to the grand Romantic theatre of Nature, History and Myth. The results. however, suggest that such a speculative renewal is impossible. He does not have the language, the many-layered figurative vocabulary, or the allegorical vehicles for this. Most decisive. however, is the fortunate fact that we have lost our belief in myths and in their actuality. They no longer affect us. whereas in former times of deprivation and despondency they buoyed us up. By contrast, today's priest is expected to overdose us with woefulness.[2]

The historical episodes Kiefer convenes in his painting are like accumulations of sediment. The handwritten names of the (usually) unseen protagonists and locations have a peculiar eloquence, and function like Brechtian distancing effects. In some compositions the bark-like layer of pigment looks crusty, as though it had been baked. The body of the painting is like a cross-section of a geological formation, rich in sand, straw, animal hide, metal, wood, paper and papier-mache. Kiefer also makes complex montages of woodcuts that remind one of the altar wings used to frame a central allegory. In painting over huge landscape photographs, his main quest is to find his (spiritual) forefathers. The quest is necessarily preceded by the expiation, through a painterly fiction, of memory. The sedimentary layers here are also those of the taboo.

At Documenta 6 (1977), Kiefer became known as more than just a regional painter. Then, with A New Spirit in Painting in London and Westkunst in Cologne (both 1981) and the Zeitgeist show in Berlin in 1982, he was hailed as a key figure on the German art scene. According to the New York Times critic John Russell. the birth of Anselm was one of the great blessings to befall Germany in 1945. His German colleagues have not been so enthusiastic. When Kiefer and Baselitz were presented at the 1980 Venice Biennale, most newspapers reacted negatively. The titles of the large-format paintings Germany's Spiritual Heroes (1973) and Parsifal (1973) were in themselves enough to provoke hostility. Recently however, after the exhibition organized by W.A.L. Beeren at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1986-87, journalists have begun to express more positive opinions.

At the beginning of the seventies, Kiefer tended to paint in a more graphic style using powerful perspectives in theatrical spaces: bare attics and warehouses, yawning spaces filled with wooden beams, often covered with a crude coating that produces an oppressive, medieval Nordic atmosphere. With the help of little name tags and small flames, swords and wings, the viewer's fantasies drift off in the direction of the Nibelungenlied and the sagas of the Edda. By the beginning of the eighties, Kiefer had begun to use architectural motifs again, though now his subjects were drawn from recent German history, notably the buildings designed by the Nazi architects Speer. Kreis and Troost. In 1984 Karin Thomas gave this account of Keifer's evolution in the magazine Weltkunst:

This work marks the culmination and confirmation of a heroic sentimentalism about a form of architecture which history itself has emptied of all feeling—and which, for this reason, seemed predestined to be of significance for Kiefer. Such architecture attracts Kiefer because he wants to determine the meaning and the potential energy of art when it is placed in the middle of Speer's Nazi space, a space which seems to evacuate all space: a tiny palette rises like a Grail and charges the cavernous, heroic atmosphere with its energy. Painting is rebirth and transfiguration, a power akin to the spiritual force of angels. Kiefer evokes a secondary theme—his own ars pictura—in the often ironic, apocryphal images of apocalypse, in the monumental Tomb of the Unknown Painter... One hopes that Kiefer's pictures will not give the wrong impression in the upcoming shows in France and Israel, but that they will, on the contrary, show why, though German history and mythology have been suppressed up till now, these two spiritual realities have not been eliminated from the national heritage. Kiefer has the courage to exorcize the terrible results of these myths so as to address their content with lucidity.

It is really impossible to interpret these paintings as heroic and pro-German, since a fragmentation of the subject clearly militates against any sentimental feeling. Moreover, all the emblems of power look broken down and ludicrous, for instance the lead propeller, the clapped-out wings or the useless Jacob's ladder. A hero couldn't travel very far with such dilapidated equipment: even mythological high-flyers come to grief with Kiefer's aerial instruments. What the viewer senses above all is, in the words of the critic Marie-Luise Syring, a "cult of failure."

Only the palette, the recurring symbol of Kiefer's craft ("Symbols are important for me"), seems to escape injury. The palette is at once a life buoy and an anchor of hope. The palette seems to hover above us, and, under its sign, one inhabits a space that is half noble and half ridiculous. Sometimes, the palette is seen looming above a grave. equipped with light blue wings (Resumptio, 1974), or being used like a shield in The Painter's Guardian Angel (1975). In The Tomb of the Unknown Painter (1974). Kiefer makes a heroic comparison with the unknown soldier. According to the unmistakable message, the painter goes about the world with a sacred palette, destroying with a sword of fire but also creating the world anew.

"When it is said that Kiefer has made painting important again," wrote the journalist Petra Kiphoff, "this claim is meaningful only in the sense that, in his best works, he transforms painting into reality, into a presence which grief can nonetheless destroy, into an ambivalent feeling about what one already knows. Kiefer's theme is the fact of being, as it were, a posthumous painter." She argues that Kiefer's work is preceded by the Word:

With spiritual heroes like Wayland the Smith, Icarus, Wagner or Stefan George, it is clear that Kiefer feels that the Word saves one from banality... Manifestations of the Word are found in the stories of Theodor Fontane and in the Edda, in obscure anthologies and in Richard Wagner, in German myth and history, in the story of Arminius the Cherusker or in Hitler's planned invasion of England. Operation Sea-Lion. Kiefer's subjects come from a very literary past and are often associated with the present (in photos of his workshop or of the nearby countryside). In this way, myth appropriates the power of the present moment, and the historical event takes on the quality of myth.[3]

Several years earlier a completely different tone was to be found in Die Zeit. On the occasion of a Kiefer exhibition in 1981 at the Folkwang Museum in Essen, the local correspondent wrote a small article about a "harvest festival of kitsch." To him, the painting Poland Is Not Yet Lost only brought "Germany's megalomania" to mind.

When in 1969 Kiefer made a book called Occupations, with photographs of himself giving the Hitler salute around Europe, reactions varied between amazement and revulsion. Fifteen years later, in a conversation with the German magazine Art, Kiefer commented: “I identify myself neither with Nero nor with Hitler. However. I must sympathize with them just a little bit so as to understand their madness... Art for me is simply the possibility of creating relationships between disparate things and in that way giving them a meaning."

As for the recurring practice of painting over huge photographs. Kiefer has said:

The photo on the canvas is a reality that beckons me; I cover up the pure reality of the photograph with my thoughts and feelings, since I paint in layers. Each layer shines through, and so I work according to a kind of "inverted archaeological" principle. I begin work with the greatest degree of imprecision and arrive at the greatest possible clarity—in the sense of giving a meaning.

At the beginning of her catalogue to an exhibition of Kiefer's books and gouaches in 1983, Katherina Schmidt, the former director of the Baden-Baden Kunsthalle, quoted a maxim by the eighteenth-century philosopher Giovanni Vico. The maxim throws a wonderfully clear light on the linking of history and mythology in painting. "Man," wrote Vico, "can only understand what he himself creates." And as the philosopher Ernesto Grassi commented:

One concludes from this that the only thing that man really can apprehend is history, since history is his creation. In so far as history is man's own self-realization, art plays a decisive role in laying down the first principles of human knowledge and always functions as a component of the human spirit and its development. The first step of culture is a poetic one. Man "thinks" in poetic form, with images from his imagination. This is why myths are so important in the first stages of art.

The anxieties of a society that has developed without creating its history are mirrored in Kiefer's work. Perhaps his real importance lies here, as a painter who has taken modern man back to his own "first stages."

Notes

1 Rheinischer Merkur / Christ und Welt. 6 June 1980.

2 Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 11 April 1984.

3 Die Zeit, 13 April 1984.