Introduction: Last year at Marienbad

Last Year at Marienbad 1961

Alain Resnais and I are often asked how we worked together on the conception, writing and shooting of this film. Merely answering this question will provide a whole point of view with regard to cinematic expression.

The collaboration between a director and his script writer can take a wide variety of forms. One might almost say that there are as many different methods of work as there are films. Yet the one that seems most frequent in the traditional commercial cinema involves a more or less radical separation of scenario and image, story and style; in short, "content" and “form."

For instance, the author describes a conversation between two characters, providing the words they speak and a few details about the setting; if he is more precise, he specifies their gestures or facial expressions, but it is always the director who subsequently decides how the episode will be photographed, if the characters will be seen from a distance or if their faces will fill the whole screen, what movements the camera will make, how the scene will be cut, etc. Yet the scene as the audience sees it will assume quite different, sometimes even contradictory meanings, depending on whether the characters are looking toward the camera or away from it, or whether the shots cut back and forth between their faces in rapid succession. The camera may also concentrate on something entirely different during their conversation, perhaps merely the setting around them: the walls of the room they are in, the streets where they are walking, the waves that break in front of them. At its extreme, this method produces a scene whose words and gestures am quite ordinary and unmemorable, compared to the forms and movement of the image, which alone has any importance, which alone appears to have a meaning.

This is precisely what makes the cinema an art: it creates a reality with forms. It is in its form that we must look for its true content. The same is true of any work of art, of a novel, for instance: the choice of a narrative style, of a grammatical tense, of a rhythm of phrasing, of a vocabulary carries more weight than the actual story. What novelist worthy of the name would be satisfied to hand his story over to a “phraseologist" who would write out the final version of the text for the reader? The initial idea for a novel involves both the story and its style; often the latter actually comes first in the author's mind, as a painter may conceive of a canvas entirely in terms of vertical lines before deciding to depict a skyscraper group.

And no doubt the same is true for a film: conceiving of a screen story, it seems to me, would mean already conceiving of it in images, with all the detail this involves, not only with regard to gestures and settings, but to the camera's position and movement, as well as to the sequence of shots in editing. Alain Resnais and I were able to collaborate only because we saw the film in the same way from the start; and not just in the some general way, but exactly, in the construction of the least detail as in its total architecture. What I wrote might have been what was already in his mind; what he added during the shooting was what I might have written.

It is important to stress this point, for so complete an understanding is probably quite rare. But it is precisely this understanding that convinced us to work together, or rather to work on a common project, for paradoxically enough, and thanks to this perfect identity of our conceptions, we almost always worked separately.

Initially, it was the producers who had the notion of bringing us together. One day late in the winter of 1959-60, Pierre Courau and Raymond Froment asked me if I would like to meet Resnais, with the idea of eventually writing for him. I immediately agreed to the meeting. I knew Resnais' work and admired the uncompromising rigor of its composition. In it I recognized my own efforts toward a somewhat ritual deliberation, a certain slowness, a sense of the theatrical, even that occasional rigidity of attitude, that hieratic quality in gesture, word and setting which suggests both a statue and an opera. Lastly, I saw Resnais' work as an attempt to construct a purely mental space and time—those of dreams, perhaps, or of memory, those of any affective life—without worrying too much about the traditional relations of cause and effect, or about an absolute time sequence in the narrative.

Everyone knows the linear plots of the old-fashioned cinema, which never spare us a link in the chain of all-too-expected events: the telephone rings, a man picks up the receiver, then we see the man on the other end of the line, the first man says he's coming, hangs up, walks out the door, down the stairs, gets into his car, drives through the streets, parks his car in front of a building, goes in, climbs the stairs, rings the bell, someone opens the door, etc. In reality, our mind goes faster—or sometimes slower. Its style is more varied, richer and less reassuring: it skips certain passages, it preserves an exact record of certain "unimportant" details, it repeats and doubles back on itself. And this mental time, with its peculiarities, its gaps, its obsessions, its obscure areas, is the one that interests us since it is the tempo of our emotions, of our life.

These were the things Resnais and I talked about during our first meeting. And we agreed about everything. The following week, I submitted four script projects; he said he would be willing to shoot all four, as well as at least two of my novels. After thinking it over a few days we decided to begin with Last Year at Marienbad, as it was already called (or sometimes only Last Year).

Then I began to write, by myself, not a "story" but a direct shooting script, in other words a shot-by-shot description of the film as I saw it in my mind, with, of course, the corresponding dialogue and sound. Resnais came regularly to look at the text and make sure that everything was going as he imagined it himself. Once this writing was finished we had a long series of discussions, which again confirmed our complete agreement. Resnais understood so perfectly what I wanted to do that the few changes he suggested—at certain points in the dialogue, for instance—always followed my own intention, as if I made notations on my own text.

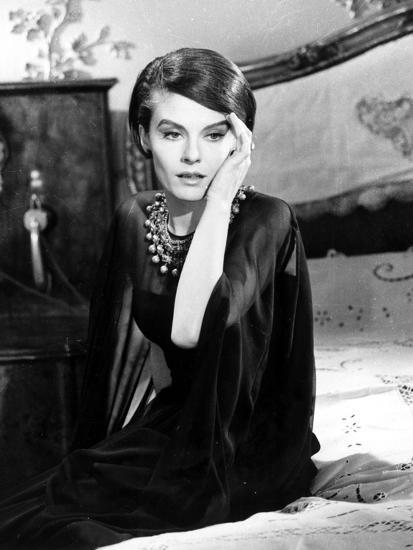

The actual shooting proceeded in the same way: Resnais worked alone—that is, with the actors and with Sacha Vierny, the director of photography, but without me. I never even set foot on the set, for I was in Brest and then in Turkey while they were shooting in Bavaria and later in the Paris studio. Resnais has written elsewhere about the strange atmosphere of those weeks, in the icy châteaux of Nymphenburg, in the frozen park of Schleissheim, and about the way Giorgio Albertazzi, Delphine Seyrig and Sacha Pitoefi gradually identified themselves with our three nameless characters who had no past, no links among themselves except those they created by their own gestures and voices, their own presence, their own imagination.

When I returned to France and finally saw the film, it was already at the rough-cut stage, having already virtually achieved its form; and that form was indeed the one I had wanted. Resnais had kept as close as possible to the shots, the setups, the camera movements I suggested, not on principle but because he felt them in the same way I did; and it was also because he felt them in the same way that he had changed them when it was necessary. But of course he had in every case done much more than merely respect my suggestions; he had carried them out, he had given everything in the film existence, weight, the power to impose itself on the spectator's senses. And then I understood everything he had put in himself (though he kept insisting he had merely "simplified"), everything that was not mentioned in the script and that he had had to invent, in each shot, to produce the strongest, most convincing effect.

All that remained for me to do was complete a few transition passages in the text, while Henri Colpi added the finishing touches to the editing. And now I can point to no more than one or two places in the whole film where perhaps ... : here a caress I saw as less explicit, there a mad scene that could have been a little more spectacular.... But I mention these trifles only for conscience's sake, since we had even intended, at the end, to sign the completed film jointly, without separating scenario from direction in the credits.

But wasn't the story itself already a kind of direction of reality? A brief synopsis is enough to show the impossibility of using it as the basis for a film in traditional form, I mean a linear narrative with "logical" developments. The whole film, as a matter of fact, is the story of a persuasion: it deals with a reality which the hero creates out of his own vision, out of his own words. And if his persistence, his secret conviction, finally prevail, they do so among a perfect labyrinth of false trails, variants, failures and repetitions!

This takes place in an enormous hotel, a kind of international palace, huge, baroque, opulent but icy: a universe of marble and stucco, columns, moldings, gilded ceilings, statues, motionless servants. Here the anonymous, polite, no doubt rich, idle guests observe—seriously though without passion—the strict rules of their games (cards, dominoes ...), their ballroom dances, their empty chatter, or their marksmanship contests. In this sealed, stifling world, men and things alike seem victims of some spell, as in the kind of dreams where one feels guided by some fatal inevitability, where it would be as futile as to try to change the slightest detail as to run away.

A stranger wanders from one salon to another—alternately full of elegant guests, or empty—opens doors, bumps into mirrors, follows endless corridors. His ears register snatches of phrases, chance words. His eyes shift from one nameless face to another. But he keeps returning to the face of a young woman, a beautiful perhaps still living prisoner of this golden cage. And so he offers her the impossible, what seems most impossible in this labyrinth where time is apparently abolished: he offers her a past, a future and freedom. He tells her that he and she have already met the year before, that they had fallen in love, that be has now come to a rendezvous she herself had arranged, and that he is going to take her away with him.

Is the stranger a mere seducer? Is he a madman? Or is he simply confusing two faces? The young woman, in any case, begins by treating the situation as a joke, a game like any other, intended merely to amuse. But the man is not laughing. Stubborn, serious, convinced of this past meeting that he gradually records, he insists, offers proof.... And the young woman, little by little, almost reluctantly, gives ground. Then she grows frightened. She draws back. She doesn't want to leave this false but reassuring world of hers which she is used to and which is symbolized for her by another man, solicitous, disillusioned and remote, who watches over her and who may in fact be her husband. But the story the stranger is telling assumes ever greater reality, becomes more and more coherent, increasingly present and irresistibly true. Present and past, finally, are intermingled, while the growing tension be-tween the three protagonists creates fantasies of tragedy in the heroine's mind: rape, murder, suicide....

Then, suddenly, she is ready to yield.... She already has yielded, in fact, long since. After a final attempt to resist, to offer her guardian a last chance of winning her back, she seems to accept the identity the stranger offers her, and agrees to go with him toward something, something unnamed, something other: love, poetry, freedom ... or maybe death....

Since none of these three characters has a name, they are represented in the script by simple initials, for the sake of convenience alone. The man who is perhaps the husband (Pitoeff ) is designated by the letter M, the heroine (Seyrig) by an A, and the stranger (Albertazzi) by the letter X, of course. We know absolutely nothing about them, nothing about their lives. They are nothing but what we see them as: guests in a huge resort hotel, cut off from the outside world as effectively as if they were in a prison. What do they do when they are elsewhere? We are tempted to answer: nothing! Elsewhere, they don't exist. As for the past the hero introduces by force into this sealed, empty world, we sense he is making it up as he goes along. There is no last year, and Marienbad is no longer to be found on any map. This past, too, has no reality beyond the moment it is evoked with sufficient force; and when it finally triumphs, it has merely become the present, as if it had never ceased to be so.

No doubt the cinema is the preordained means of expression for a story of this kind. The essential characteristic of the image is its presentness. Whereas literature has a whole gamut of grammatical tenses which makes it possible to narrate events in relation to each other, one might say that on the screen verbs are always in the present tense (which is what is so strange, so artificial about the "novelized films" which have been restored to the past tense so dear to the traditional novel!): by its nature, what we see on the screen is in the act of happening, we are given the gesture itself, not an account of it.

Yet the most narrow-minded spectator has no difficulty understanding the flashback; a few blurry seconds, for instance, are enough to warn him of a shift to memory: he understands that from this point on he is watching an action in the past, and the sharp focus can then be resumed for the remainder of the scene without his being disturbed by an image which is really indistinguishable from the present action, an image which is in fact in the present tense.

Having granted memory, the spectator can also readily grant the imaginary, nor do we hear protests, even in neighborhood movie theaters, against those courtroom scenes in a detective story when we see a hypothesis concerning the circumstances of a crime, a hypothesis that can just as well be false as true, made mentally or verbally by the examining magistrate, and we then see, in the same way, during the testimony of various witnesses, some of whom are lying, other fragments of scenes that are more or less contradictory, more or less likely, but which are all presented with the same kind of image, the same realism, the same presentness, the same objectivity. And this is equally true if we are shown a scene in the future imagined by one of the characters, etc.

What are these images, actually? They are imaginings, an imagining, if it is vivid enough, is always in the present The memories one "sees again," the remote places, the future meetings, or even the episodes of the past we each mentally rearrange to suit our convenience are something like an interior film continually projected in our own minds, as soon as we stop paying attention to what is happening around us. But at other moments, on the contrary, all our senses are registering this exterior world that is certainly there. Hence the total cinema of our mind admits both in alternation and to the same degree the present fragments of reality proposed by sight and hearing, and past fragments, or future fragments, or fragments that are completely phantasmagoric.

And what happens when two people are exchanging remarks? Take this simple dialogue:

"What if we went to some beach? A huge, empty beach where we'd lie in the sun...."

"With the weather we're having? We'd spend the day inside, waiting for the rain to stop!"

"Then we'd make a wood fire in the big fireplace...." etc.

The street or the room where they are has disappeared from the minds of the speakers, replaced by the images each suggests. There is actually an exchange of views between them: the long strip of sand where they are lying, the rain streaming across the panes, the dancing flames. And the cinema audience would certainly have no difficulty understanding if what was shown was not the street or the room, but instead—and while listening to the dialogue—the couple lying on the sand in the sun, then the rain falling and the characters taking shelter in the house, then the man, as soon as they are inside, arranging the logs on the hearth....

In this context, it is apparent what the images of Last Year at Marienbad might be, since the film is in fact the story of a communication between two people, a man and a woman, one making a suggestion, the other resisting, and the two finally united, as if that was how it had always been.

Hence the movie audience seemed to us already well prepared for this kind of story by its acceptance of such devices as the flashback and the objectivized hypothesis. It will be said that the spectator risks getting lost if he is not occasionally given the "explanations" that permit him to locate each scene in its chronological place and at its level of objective reality. But we have decided to trust the spectator, to allow him, from start to finish, to come to terms with pure subjectivities. Two attitudes are then possible: either the spectator will try to reconstitute some "Cartesian" schema—the most linear, the most rational he can devise—and this spectator will certainly find the film difficult, if not incomprehensible; or else the spectator will let himself be carried along by the extraordinary images in front of him, by the actors' voices, by the sound track, by the music, by the rhythm of the cutting, by the passion of the characters … and to this spectator the film will seem the "easiest" he has ever seen: a film addressed exclusively to his sensibility, to his faculties of sight, hearing, feeling. The story told will seem the most realistic, the truest, the one that best corresponds to his daily emotional life, as soon as he agrees to abandon ready-made ideas, psychological analysis, more or less clumsy systems of interpretation which machine-made fiction or films grind out for him ad nauseam, and which are the worst kinds of abstractions.

The text that follows is in principle the one given to Resnais before the shooting began, made somewhat more accessible by a slightly different presentation (sound and image, for instance, originally on separate pages). But even at that stage we had anticipated that certain passages of the offscreen narrative (that is, spoken by the voice of a character not on the screen) should be changed or enlarged during the editing, in consideration of the final image (to obtain a precise correspondence of content or duration); these few phrases have therefore been replaced in the original text.

The attentive spectator will naturally notice, discrepancies between this account of a film and the actual film as seen. These slight changes have either been dictated by material considerations, such as the architectural arrangement of the settings used, even sometimes by a simple concern for economy, or else imposed on the director by his own sensibility. But it is not to dissociate myself from Alain Resnais' mediations that I present my initial text here, for on the contrary that text has only been reinforced, as I have indicated above; the only reason is one of probity, since the text is published under my signature alone.

The reader will find few technical terms in these pages, and perhaps the indications for editing, set-up shots and camera movements will make the specialist smile. This is because I was not a specialist myself, and because I was writing a shooting script for the first time. I hope that in any case this factor will make reading the scenario less tedious for a larger public.

Alain Robbe-Grillet