Wool's Word Paintings: Greil Marcus

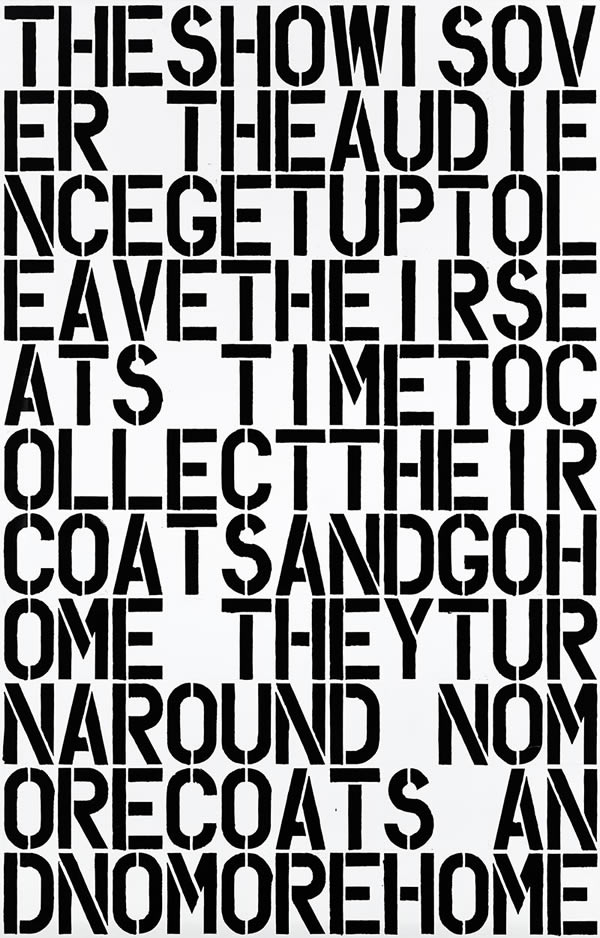

Christopher Wool. Untitled. 1990

One of the energy sources in Christopher Wool's word paintings is that they appear not on the street, stenciled and blunt on tenement walls, construction site fences, or hoardings bearing generations of photocopied ads, announcements, and propaganda ("Absolutely Queer"), but rather in galleries, museums, and Wool's own books. It feels as if it ought to be the other way around. The paintings seem to ask for different settings, different media than Wool's usual sign painter's enamel on aluminum.

In such pieces as APOCALYPSE NOW ("SELL THE HOUSE SELL THE CAR SELL THE KIDS"), UNTITLED (1989) picturing "AMOK" (rendered as "AM OK," as in "[I] am o.k."), or UNTITLED ("THE SHOW IS OVER THE AUDIENCE GET UP TO LEAVE THEIR SEATS TIME TO COLLECT THEIR COATS AND GO HOME THEY TURN AROUND NO MORE COATS AND NO MORE HOME")'—quoted by Situationist Raoul Vaneigim as "the best definition of nihilism" from the writings of the pre-revolution Russian Nietzschean critic Vasili Rozanov—the voices have a quality that falls somewhere between the ranter screaming on the corner ("There are more young African-American men in prison than in college!") and the person a few steps down the block handing out commercial flyers ("Good For one Free visit to Armando's House of Pain").

You walk into a gallery around the corner and come face to face with "CATS IN BAG BAGS IN RIVER," or just "RUN," and they communicate not like facile appropriations of primitivist street discourse, but as a honed, perfectionist idea of that discourse, reduced to the irreducible and then starting up all over again. The overall impression is of a voice struggling against muteness (as a social disease), or against censorship (not our half-hearted, legalistic, carrot-and-stick version, but the real, totalitarian thing), in any case against silence, and keeping the game going. The pieces are dramatic, which is to say loud; they are also cryptic, hushed. With more than two in a room, or with many together in the pages of Wool's books, his 1989 BLACK BOOK or the 1991 CATS IN BAG BAGS IN RIVER, the pieces speak in harsh whispers: "And now," as the Firesign Theater once put it, "the rumors behind the news."

The appearances of Wool's word-pictures off the street, though, have an odd effect on the domain from which they seem to have been lifted, where you think they must have been found: they expose what's missing in the public language, the public space, from which they seem to emanate. Look at the graffiti on the walls of your town, or the billboards, or neon signs—there's nothing like Wool's work there. And yet the work is anything but hermetic, or formalistic, or a conceit. Even in a gallery or a museum—or especially there—the paintings are almost screaming to get out, like the figures in Manual Valdes and Rafael Solbes's LA VISITA (1969), a painting that shows GUERNICA on a museum wall, missing the nearly prostrate woman and the severed head-and-arm, which are on the floor, reaching for the door. The public dimension of Wool's pictures—their noise—is undeniable. Like dada, they are pure protest, means without ends: self-made sites where the aesthetic turns into the political, and vice versa.

Now, it used to be that if you wanted to send an art-message, you called Barbara Kruger or Jenny Holzer. Through no fault of the artists, they came to be seen not merely to practice political word-art but to stand for it. Kruger's use of the same smooth, sans-serif typeface in every picture became like a trademark, or a signature, an image-in-itself that silenced its message, that one read as "Political" rather than for whatever the typeface, in a given case, did say.[1] It may be a matter of simple familiarity, but right now Kruger's work communicates glamor more directly than it communicates anything else. This message reads immediately, as a tease, so that, now, when you look at a Kruger work, it seems to promise infinitely more than you can get out of it. Time will tell if such a fate overtakes Wool's work, which features the same trademarking as Kruger's—though Wool's packing-crate stencil alphabet is self-evidently not his own, the only really found element in his paintings, and even that is smeared with drips and errors and out-of-place letters bumping up against each other where they don't belong, unlike the always precise, machine-made lettering Kruger uses. Kruger's letterings look like advertising: that's her joke, even if it gets her. Wool's lettering looks like work. As you read his "SELL THE HOUSE, SELL THE," you read "PERISHABLE THIS SIDE UP" behind it.

If the work of Kruger and Holzer reads lucidly (that lucidity hopefully working as an entree into the subconscious of the viewer, where it will become subversion), Wool's work is, at its best, hard to read. Close up, you see that the received statement, "THE SHOW IS OVER..." (and single words used by Wool, like "FOOL" or "RIOT," are no less received), has been subjected to the vagaries of its making. It would not come out the same way twice, even if the spacing were the same. This philosophical statement about the meaning of life is subjective before it is anything else. As an image/message, it is unstable; like any work of art, it is unlikely. Wool's studio is full of out-takes, discarded versions of the same thing. You look at several, one after the other, and realize that "THE SHOW IS OVER" could read as a homily as easily as it might cut your heart. It can be shocking to realize that a word that trumpets its naturalism ("RUN") or a line that preens in its media hipness ("SELL THE KIDS..."—a quote from Frances Coppola's Apocalypse Now) might, according to whether or not the painter had a hangover that day, work or not.

Wool's word paintings take place in a realm between theory and accident. They suggest far more than they ever state and never call attention to their own preciousness, which is real and fecund (the Precieuses of the 17th century built their movement around an apprehension of words as objects not only of meaning, but of power). It is crucial, in Wool's ambitions, that you see what he does as one person's work (it is not crucial that you see it as necessarily his; the point is, it might not have happened). He is, he says, "the kind of painter who still believes in the aura of painting" [2]—which, to my mind, has more to do with event than personality, with happenstance than genius. But this is work in which the happenstance is made to happen, and the personality—though not its subjectivity—is made to disappear.

You can see this—read it—in Wool's book CATS IN BAG BAGS IN RIVER. ('"My vision' of my work," Wool writes.)[3] Published as a skewed exhibition catalogue in an edition of 2500, the book is in fact just a bound collection of color photocopies. Mixing in a lot of Wool's patterned paintings, which range from sheets of rosettes to sheets of gargoyles, the book expands Wool's field of action with detail-blowups in the manner of Michael Lesy's 1973 Wisconsin Death Trip, a photo/text documentary history of the 1890s depression as it affected a single, small Midwestern community. Here, though, it's not terrified faces, or sometimes just the eyes, pulled out of nice group photos, but words pulled out of their phrases, or even parts of letters jerked out of their words. Suddenly, as you look at the garishly colored photocopies, language appears as an altogether arbitrary construction and also as an irreducible construct, a fact that we cannot escape. Wool breaks up words, ignoring the dictates of word-shape and even letter-shape: in CATS IN BAG the curves of an O or a U can look like parts of bridges, not letters. You can't look at the parts without knowing that they mean to communicate more than Wool is trying to keep them from saying (or pretending to keep them from saying); you can't look at the parts without realizing that, even stripped and mutilated, bent out of shape, they can say almost anything. Words cannot be silenced, Wool might be saying—but we're working on it!

That "we" of my imagination, of my response to Wool's work, implying troops and a plan, might be the only possible objective, ideological element in Wool's paintings. Otherwise they are subjective occasions that in antithesis to any hegemonic formation shout out their unnaturalness—as in Wool's BLACK BOOK. This is a slim, oversized volume with words on the right hand side (the facing pages are left blank) beginning with

SPO

KES

MAN

rendered as stacked components and following with INSOMNIAC-PESSIMIST-PRANKSTER-CHAMELEON-ADVERSARY-COMEDIAN-TERRORIST-HYPNOTIST- HYPOCRITE-CELEBRITY-AUTHORITY-EXTREMIST-PERSUADER-ASSISTANT- ASSASSIN-PARANOIAC. What this is, you might think, is nothing more or less than a directory of basic social roles, of individuals reduced to certain social functions. The title BLACK BOOK works wonders. The standard notion of "the little black book," the book of sex contacts or of future victims, is erased straight off; as a reference to "black propaganda" or "black budgets"—whatever takes place off the books, that is prima facie covered up, written out of history, stuff that's unjustifiable in public but privately necessary, the lifeblood of state policy and control—the BLACK BOOK is one person's directory of secret social agents. You page through it; you wonder what role you've been assigned, or accepted.

No sense of art accompanies a reader as s/he moves through this odd artist's book, published in an edition of 350 but perhaps provoking you to fantasize a much wider distribution: all seventeen words on postcards, on walls—all seventeen words on a single building, or each word on a sequence of seventeen buildings. The sense of the implacable, the irreducible, that's present in all of Wool's word paintings—the sense of dread, the free-floating, agentless threat—rises up here. It rises up, and turns into fun: the fun Wool has obviously taken in discovering how much power is secreted in a different vision of an ordinary word, in a car-crash version of an unknown statement, like somebody's "The show is over" turned into "THESHOWI SOV" Like all letter-painters—for with Wool's work you ultimately leave the phrase, the word, and wonder about the letter, the constituent element, now out of place—Wool is a punner, and a fan. I mean that he is interested in the constituent elements of our everyday talk ("RUN," or "RU/N") and also happy about the ways in which they combine. Wool works as the ranter on the street, proclaiming the end of the world ("NO MORE COATS AND NO MORE HOME"), but also as the person handing out the flyers, an anonymous worker in culture. Wool's UNTITLED (1989) with its six lines of "Please"'s,

PLEASE

PLEASE

PLEASE

PLEASE

PLEASE

PLEASE

can be read as "the plea of a victim,”[4] but it's also a reference to James Brown's first hit, "Please, Please, Please," which made the charts in 1956, the year after Wool was born, and which has not been off the radio since. Wool looks you in the face; he says what you're used to hearing; he disrupts the communicative power of words; he affirms the communicative power of letters. Someone is shouting, but you can't tell if that person is trying to make you understand or insisting that you don't have a clue.

Notes

1 In 1989, at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, as the show On the Passage of a Few People Through a Rather Brief Moment in Time The Situationist International, 1957-1972 was going up, designer Christophe Egret was appalled to see that the situationist slogans he'd given to an assistant for placement on a pillar had all been rendered in Kruger-type "Do you see what's happened?" he said, instinctively translating words and images. "People think the only way they can make political art, the only way anyone could have ever made it, is by speaking her language!” The situation became so generic, which is to say so depoliticized, that by 1991 a movie so cheesy it premiered on video—Dennis Hopper's Backlash, where Jodie Foster played an artist who was Holzer in every way save her name and Hopper played a hit-man on her trail—could get the joke that art many had been pleased to call subversive had become indistinguishable from fashion. Having witnessed a mob killing, Foster's artist changes identities and goes to work for an advertising agency, Hopper's hit-man, who's been poring through back issues of Artforum in hopes of getting a fix on his prey, tracks her down when he opens a glossy magazine to a two-page ad for cosmetics, headlined "Protect Me From What I Want " You can stop the tape, freeze the frame of the advertisement, all lipstick-red, and realize that there has been no loss of meaning in the transfer of Holzer-Foster's once blank, uncontextualized line from art to commerce, instead you realize it is more effective selling makeup than shaking anybody up.

2 Christopher Wool in correspondence with GM, 3 August 1991.

3 Ibid.

4 John Caldwell, "Christopher Wool—New Work" San Francisco Museum of Modem Art, exhibition catalogue, 1989.