Christopher Wool New Work: John Caldwell

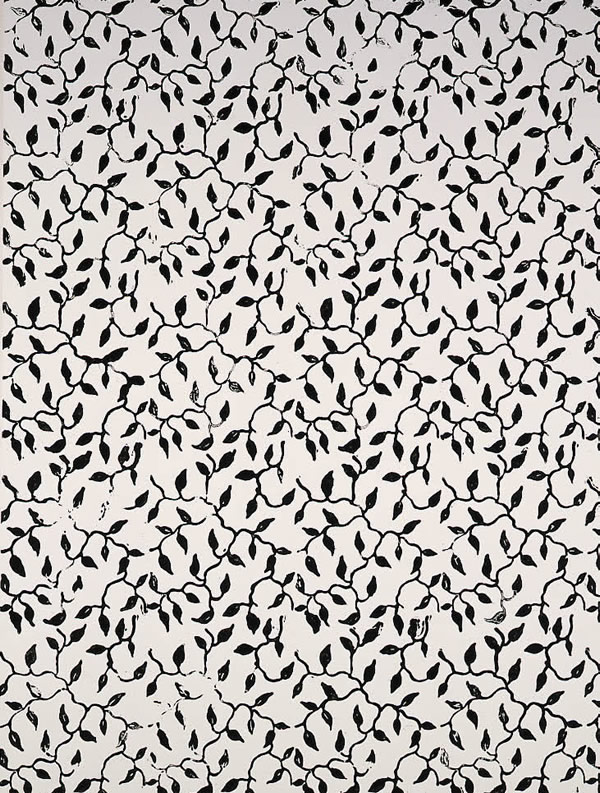

Christopher Wool. Untitled. 1988

Although he has explored other art forms, including film, what Christopher Wool considers his mature work began with paintings he made in 1984. At that time, he was dissatisfied with the work he was producing (for example, a painting called Bigger Questions, which was simply a question mark on its side). Like many artists before him, he began to investigate the basic processes of painting itself. "struggling to find some kind of meaningful imagery.”[1] A work he called Zen Exercise consisted of three large, violent pours of paint. Looking back today he considers this work crucial because the pours were random, and he was "looking for location.”

In the following year, with an enamel on plywood painting entitled Houdini, Wool continued his arbitrary paint application by dripping and spattering white paint onto a black surface. At first glance, Houdini looks like a Jackson Pollock achieved by recourse to the methods of John Cage: the evidently random drops of paint occasionally coalesce into larger, driplike patterns. One suspects that this adventitious painterliness was both too lush and too ambiguous for the artist, because for the next two years he produced paintings in which the application of paint was rigorously even. The result was paintings with allover compositions that although random were everywhere uniform, with no runs and only occasional larger dots of paint where one drop collided with another.

Standing before such paintings for the first time is a curious experience. One thinks naturally of Pollock because of the way the paint is dripped onto the metal support, but to remember Pollock is necessarily to experience a sense of loss. Instead of his looping whorls of paint, seemingly uncontrolled, but in fact highly disciplined, one faces in Wool's work only the arbitrary order of carefully achieved randomness. Undeniably the work is beautiful; for many observers it resembles stars in a night sky. Yet, especially because of the inevitable recall of Pollock's work, there is no secure sense of what Wool's paintings mean. They are uniform, deliberate, absolute, and masterful, but entirely resistant to one's natural search for meaning, which they seem to deny.

One of the things they are about, as slowly becomes evident from repeated viewings of these and subsequent works, is the process of painting itself. Wool describes himself at this period as moved by the great care several artist friends took with their work. Always before he had proceeded in the belief that how a work of art was made was irrelevant, but now craft became important as he attempted the seemingly easy yet actually quite difficult process of random but uniform application of drops of paint to a surface. In doing so, as the artist put it, "process became image.”

For Wool, the central issue raised by these paintings and all of his subsequent work is freedom versus control, and one sees clearly in the paintings of 1985 and 1986 the absolute liberty implied by random application of paint constrained by an artistic decision to achieve a uniform, allover composition. With this decision, moreover; Wool established a principle he has followed ever since: each work exemplifies a single process and because the process is evident, the statement appears as both arbitrary and complete. The artist's intention is fully expressed.

Almost as soon as he had mastered the dripping process, producing works with quite astonishingly varied surfaces, Wool turned to another method of applying paint, the ordinary paint roller. For him it was "conceptually the same as dripping, just another tool to cover a canvas in that simple, pure way." The rollers Wool chose to use were not the usual ones, developed purely for efficiently covering walls with paint, but specialized rubber cylinders that he purchased at hardware stores, incised in such a mannerthat rolling them over a surface produced a pattern similar to wallpaper. The patterns Wool chose were first small flowers, then leaf patterns. Although he sees them as "organic" forms with "landscape qualities;' the experience of looking at them is very far from pastoral. One critic described a sense of vertigo experienced before these paintings:

They offer nothing to hold on to, yet they're full, like a noise penetrating your brain and driving out your thoughts. Because of the metallic surfaces they have the physical aura of machinery or architecture. They echo the surfaces that ribbon past from a taxi or subway window; the smooth glass and polished steel of a city world-but more condensed, pressurized into a heavy portable object. Their decorative qualities are deceptions. The eye doesn't linger in one place or rove over them registering choice bits, but locks into contact with the surface and freezes into a numbed stare. They exercise an almost hideous power, like real mirrors of existence. Perhaps they are Zen objects, surfaces that absorb the spectator into nothingness, enamel rock gardens without rocks.[2]

The utter alloverness of Wool's paintings, their completeness, and what might be called their absoluteness, can be disturbing, but one suspects that the disturbance is not merely physical and psychological but existential as well, and that it arises not only from the paintings' formal designs and unyielding materials but from the way they are actually painted. None of Wool's paintings is alike, whether made with the rollers that imitate wallpaper which he first purchased ready-made and then began fabricating himself, or with the stamped floral patterns and gate images of his more recent work. Even in paintings made with the identical tool, it is clear that the artist deliberately introduced variation. In all of the paintings made with rollers, for example, there are minor imperfections and variations in the way the image is registered, but it is more significant that in many works the image is so faint at times that it almost fades away entirely. In fact, the eye does move across the paintings' surface repeatedly because in ordinary life, outside of painting, variation implies change or development, and the viewer actually tries to read the imperfections of the process for meaning. The effect turns out to be very similar to what happens in Andy Warhol's repeated silkscreen images of the early 1960s, where the slippage of the screens and the diminishing amount of pigment registered on the canvas produces the illusion but not the reality of a change in the image itself.

In Warhol's best works, the dead movie star or the electric chair seems to change, and the viewer experiences this with both relief and heightened interest, only to discover that the image is the same and that there is no escaping the harsh reality, or unreality. of the single image itself. Wool is more reticent, cooler even than Warhol. Since the repeated pattern has no inherent meaning and no strong association, we tend to view its variation largely in terms of abstraction, expecting to find in the changes of the pattern some of the meaning we associate with traditional abstract painting. We quickly discover; however, that these variations in Wool's paintings are random, and no matter how beautiful the interrupted veils of pattern may be, there is no end to their repetition. Like Warhol, Wool frustrates our search for meaning.

Wool's most recent paintings, stamped floral images in red and black on a white ground, are in several ways the purest expression of the abstract side of his work. Because more of the uninflected white paint on the metal support is visible, it is possible to see with more clarity how it functions in all of his work. The surface is absolutely smooth, flat without even the variation of visible brush strokes with the very slight spatial recession that they imply. Nor is there the visible variation in depth of surface that the weave of a canvas support would have supplied. The plane is absolutely flat, as if made by a machine. Were this not so, the large expanses of rarely interrupted white would look like defaced Rymans. As they are, they are utterly blank, and we necessarily search the randomly scattered floral motifs for significant meaning, only to find, as with the leaf and gate motifs, that none is apparent. Because they are powerful, absolute presences, despite their reticence, and because they are paintings, we are left to suspect that that is in fact an important part of their meaning, and that their blankness, their absoluteness, and their refusal to convey the reassuring humanism we have come to expect from abstract art, especially, is precisely their point.

With some of his paintings over the last two years, Wool has taken another direction, one that in retrospect seems inevitable because it so perfectly complements his previous work. His text paintings began when walking out of his studio in lower Manhattan one day he saw the words sex and luv written in black spray paint, one above the other; on the side of a brand new white truck. Soon after that he painted the same words on paper and began his first text painting, Trojan Horse, in which he stenciled the letters of the two words in abbreviated form in black across a white ground. It was in Apocalypse Now, the second of Wool's paintings using words, that he worked out what was to be his method. Just as he had used a readily available wallpaper pattern for his roller paintings, he took words from a preexisting source, Francis Ford Coppola's movie based on Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness, a film Wool greatly admires and has seen many times. The text is written in extremis by a Special Forces Captain, Richard Colby, who has been sent on a mission to assassinate a renegade American colonel, Kurtz, who has built a society based on horrifying, unspeakable violence in the Cambodian jungle. Colby instead decides to join Kurtz, as he attempts to inform his wife by writing a letter beginning, "Sell the House, Sell the Car, Sell the Kids.”

After Apocalypse Now, Wool made an untitled painting bearing the words Helter Helter, which immediately recall the title of a Beatles song which Charles Manson's gang wrote in their victims' blood on the walls of the house where they were killed. Another, with an abbreviated version of Mohammed Ali's description of his fighting technique, "Float like a Butterfly. Sting like a Bee", recalls first of all his dazzling skill and grace as a boxer; an association, that is, however; inevitably followed by the realization that Ali received so many blows to the head that he currently exists in a severely brain-damaged state. More recent paintings are of single words, amok and awol, one overtly and the other potentially suggesting violence. In another recent work, even an apparently ingratiating word, please, is starkly repeated six times so that it fills the surface and becomes the plea of a victim.

It is possible to read Wool's texts as, literally, the handwriting on the wall, like the words scrawled on the walls of Sharon Tate's house. Yet the words reach us abstractly. In all Wool's text paintings he uses a rigid grid to place the letters into an allover abstract pattern, almost entirely suppressing the customary space between the lines of text so that the letters form vertical as well as horizontal lines. Often, too, the words are broken arbitrarily, without regard for syllables, making the text hard to read and encouraging the viewer to see the painting first as an abstract collection of letters. When read, of course, the words are shocking indeed, but they are distanced somehow by their presentation, which makes them seem mechanical, like the letters of an electronic sign announcing a disaster. Yet in the text paintings. as in his abstract works, Wool's process is everywhere apparent. The letters are never perfectly stenciled: often the edges are imprecisely drawn, and always there are drips of paint which the artist makes no effort to conceal or remove. Like his abstract paintings, the text paintings are about the issue of freedom versus control, often in a literal sense. Captain Colby's decision to join Colonel Kurtz is after all a decision to leave the American army, a choice to go awol as it were, and the portion of his message Wool has chosen to quote is rather funny. Wool asserts his own freedom also, in a literal sense, by sometimes changing the material he quotes. He paints Helter Helter, rather than the actual title of the Beatles' song, "Helter Skelter;' raising the possibility that he has made a mistake, that he has misquoted, or that he is in fact taking some other event or none at all for his subject.

Every moment of really significant change in twentieth-century art has announced itself, or seemed to do so, as a renunciation of meaning. Picasso's and Braque's Cubist paintings, Duchamp's urinal, Pollock's drip paintings, and Warhol's early silkscreen paintings, for example, were initially received as shocking retreats from art's traditional role of communicating from one human being to another. In retrospect, of course, each of these has come to be seen as a necessary clarification of a prolix and even decadent situation–a successful effort, as it were, to purify the dialect of the tribe. Each of them, too, was moving art an important step forward toward embracing and incorporating the realities of modern life. It is too soon yet to know whether or not Christopher Wool's abstractly formal paintings of ordinary motifs and his equally formal quotations of texts that sometimes have their sources in popular media constitute a step of similar importance in the evolution of modern art. What is clear now is that the newness of his work has elements in common with what was radical in the art of many of the major figures of the art of this century. This essay explores only a few aspects of Wool's complex relationship to the art that has preceded his. Much needs to be said about his work in relation to figures other than Pollock and Warhol-Bruce Nauman, for example, and more distantly Jasper Johns. Then, too, there are important questions of where Wool stands in relation to several of his contemporaries-Robert Gober, Philip Taaffe, and Jeff Koons are those that immediately come to mind. Perhaps for the occasion of this, his first one-person museum exhibition, it is enough to point out that Wool has made work that engages some of the most important issues of the historical past of twentiethcentury art, and that he deals with what seem to be the most pressing questions of our own moment in a medium that other artists of his generation have found difficult, if not impossible: painting. Above all, Christopher Wool is a painter.

Notes

1 Unless otherwise noted, all quotes are taken from an interview by the author with the artist, 4 May 1989.

2 Gary Indiana, "Chronicle in Black and White;' Village Voice, 31 May 1987, p. 89.