Ghost Dog: Anne Pontégnie

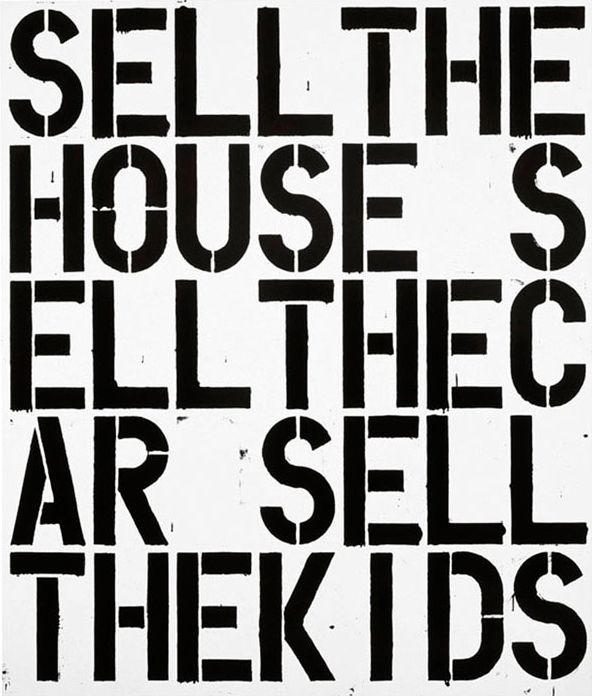

Christopher Wool. Apocalypse Now. 1988

"There will be no traffic, and the streetlights will seem to shrink back into their globes, drawing their skirts of illumination into tight circles, and the rutted streets reveal the cobbles under a thin membrane of asphalt, and the buildings all around are masses of unpointed blackened brick or cacophonies of terra-cotta bric-a-brac or yawning cast-iron gravestones, six or eight stories tall. This is the sepulcher of New York, the city as a living ruin." — Luc Sante, Low Life

When I discovered Christopher Wool's work almost fifteen years ago, I didn't understand much of it. Since then, each passing year has brought me closer to the passionate and increasingly profound interest I have in it now Along this road, catalogues, editions, posters, and photographs, gradually allowed me access to the sources of the paintings and helped to penetrate their opacity without, however, diminishing it. I wanted to devise an exhibition that would condense this experience and participate in revealing Christopher Wool's pictorial project, both in terms of its relevance and its capacity to give pleasure.

In 1991, Christopher Wool was invited to have his first solo museum show in Europe at Boijmans Van Beunigen Museum in Rotterdam. He designed a catalogue for the occasion, Cats in Bags, Bags in River, based on colour photocopies of photo-graphs of his paintings. At each of these stages, the artist used the accidents of fabrication—of framing, of focus, of tint—in order to compose a book that would stand on its own, as removed from the idea of a catalogue as possible. The black and white emblematic of his painting at that time veered toward fluorescent pinks and yellows, while the enlarged detail accentuated the accidents that punctuated the compositions, essentially floral motifs and words. While these accidents refuted any possible illusion of faithfulness between a painting and its reproduction, the issue at the outset was flaws—drips or distortions that in the paintings were the instruments of meaning and composition, the last refuge of expression. With this book, the artist whose paintings had been distinguished by their resistance to interpretation[1], emphasized the shift of meaning from the centre toward the periphery, from decision toward chance, from certitude toward instability.

Two years later, the artist was invited to spend a year in Berlin, in the residency programme of the DAAD. As a result of this stay and at the end of a long period of travel, Wool published Absent Without Leave, an artist's book that assembled two hundred black-and-white photographs taken during the year of residency, which had turned into a year of travel throughout Turkey, Eastern and Western Europe. The photocopied snapshots follow page after page, ghostly, indistinct, blurry; they merge city and countryside, east and west, day and night, past and present in a single haze of desolation. In a world inhabited by fugitive shadows and stray dogs, only a few fragments and random structures emerge: at times, baroque architecture, mosaics, or ancient ruins, at times, highways, hotel rooms, or piles of trash. The grating, foliage, and words captured at random should not be seen as the source of the paintings. In fact, they signify the contrary: that only painting as experience and individual practice allows one to give meaning to the chaos of the world and to forge a point of view from which to examine events, especially if they are small, insignificant, and ordinary[2]. The title of the book does not evoke the desertion of a Berlin residency so much as an absence inscribed at the heart of all experience. How can one look at the world without truth, or direction? Perhaps through painting born of these same absences. The fact that Wool's painting accords great importance to technique and process does not mean that it is preoccupied solely with formal questions, but that it assigns formal questions the burden of bearing all other questions. A book such as Absent Without Leave reveals how the artist came to create a unique synthesis between historically pertinent painting and a contemporary experience of the world. Beyond direct references to film, funk or punk, the issue was to use the disenchantment of the late seventies as an instrument of pictorial creation and, in a dual motion, to exploit the limits of painting to account for new realities, through intuition rather than will.

The same year, Wool abandoned the technique of rollers and rubber stamps for silkscreen printing. He began with found floral motifs, which he enlarged and repeated in dense, black layers. He continued to use the accidents inherent in the process of fabrication, but gradually transformed reduction into superimposition: the excessive straightforwardness that prevented interpretation was now replaced by an accumulation of layers[3]. It was also during this period that Wool began to take Polaroids of his paintings as part of his work process.[4] By recording each step, he preserved the provisional moments of a painting and created a distance that became a part of his decision-making process. In his studio, Wool will leave the visitor in front of his paintings, whether the paintings are finished or not, and temporarily hand over the responsibility of assessing their degree of completion. The Polaroids, and the effects they have on the painting, play the same role as these visitors: they give their opinion. This relinquishing of sovereignty is also found in the way the artist relegates his choices to tools and their malfunctioning, taking into account every limitation imposed by his chosen medium. There is humor in this sought-after powerlessness, as defined by Deleuze in Masochism: to push the law to its ultimate and absurd consequences and use it to one's own advantages[5].

On his return to New York, and in transition toward a more settled life, Wool continued taking photographs on his daily wanderings. Perhaps in homage to Weegee, of whom he is an admirer, he took photographs at night of the streets separating his Lower East Side studio and his apartment in Chinatown. Between 1994 and 1995, he took hundreds of snapshots, selecting one hundred and sixty of these images, today entitled East Broadway Breakdown[6]. Like Absent Without Leave, minus the lyricism of travel, the snapshots present a desolate world, a deserted urban landscape made up of broken-down doors, suspect stains, and abandoned cars. The cast-iron gates, mosaics, and architecture that structured Absent Without Leave made room for more fragmented, random shapes: a succession of images in undifferentiated shades of gray that immerse the viewer in this nocturnal world. Their realism has more to do with this subjectivity dissolved in its context than with any hypothetical truth of representation. In his paintings and photographs, Wool might associate with stray dogs, neurosis,[7] or debris: stains, drips, and accidents of various origins, pictorial or organic. This voluntary assimilation with degrading phenomena—another form of humor, this time, black—is the instrument that allows him to achieve the dissolution found in these photographs and gives him access to a singular vision: one that is street level.

In this sense, Wool, although close to the appropriation artists, does not consecrate loss of experience but participates, alongside Robert Gober, Mike Kelley, Martin Kippenberger, and Franz West, in breaking down modernism from below, with emphasis on the low’[8]. As with these artists, this work of undermining and emancipating involves a spark of utopia that arms Wool against cynicism, opportunism, or the regression that sometimes comes with other approaches contemporary to his. Jim Lewis remarked that Christopher Wool was obsessed with "making pictures”[9]. I would add that what transforms this obsession into a legitimate artistic project is that it is accompanied by a question as pointed as it is essential: where and how can one find the space one needs (in Wool's case, the space to make pictures)?

Wool seems to enlarge this space with each new stage of his work. Starting in 1995, the structured compositions of the paintings, already destabilized by the accumulation of layers, gradually gave way to an increasingly dense and complex entanglement. Motifs of various origins, painted or silk-screened, were copied, repeated, and superimposed. The expression and pictorialism shifted from accident toward hesitation and repentance, from the margins to the center. Sometimes, wide bands applied with a roller blocked the composition as though to hide uncontrolled bursts of spontaneity. After his retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in 1998, two elements proscribed until then appeared more and more regularly: gesture, through the intermediary of spray paint often used to draw large irregular and concentric loops, and colour, first experimented with in a series of works on paper[10]. The same shape, painted directly on the canvas in one work, could be found identical in form but reproduced in silk-screen in another, presented in smaller format or hidden under the strokes of the roller, repeated or enlarged, orange, pink, black, or red.

The exhibition that I initially envisioned was comprised only of editions, photographs, and posters. Wool suggested integrating a group of Polaroids, both documents of work and works themselves, in order to show the connections between the paintings and the objects accompanying them. When Le Consortium of Dijon and Dundee Contemporary Arts decided to present the exhibition, it became essential to include a set of paintings as well. No institution in France or Britain had ever had a Christopher Wool exhibition, and it was unthinkable to introduce his work while omitting the paintings themselves. To emphasize the photographic angle by which we were approaching the exhibition, we selected a set of recent paintings in which silkscreen printing played a preponderant role.

Ultimately, the exhibition assembles two large groups of photographs: the black-and-white images of East Broadway Breakdown printed digitally, and one hundred and fifty Polaroids documenting a period of work from 1993 to 2001. With the paintings selected, these two groups construct a portrait of the various roles photography has played in Wool's work: photography as a pictorial tool with the silkscreens, photography as work document and archive with the Polaroids, and finally photography as a point of view with the images of New York at night. While a literal relationship cannot be established between, say, a photograph's oil stain on a sidewalk and a silkscreen's large, black, distended cloud (Untitled, 2000), each of these images testifies, respectively, to the intensity and circularity of the links between a way of painting and a way of seeing the world. For many contemporary painters, photography is a means of recording what they see, which eventually becomes a reservoir of subjects, a modern alternative to sketches. For Wool, painting preexists the world or, in any case, the possibility of its perception. Approaching this work through its photographic aspects, whether Polaroid, snapshot, or silkscreen print, reveals a spectral presence. Created through distance, it inhabits Wool's work and gives it its capacity to haunt.

Translated from French by Jeanine Herman

Notes

1 "They [Wool's paintings] are uniform, deliberate, absolute and masterful, but entirely resistant to one's natural search for meaning, which they seem to deny.", John Caldwell, New Work: Christopher Wool, cat., San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1989.

2 "Perhaps a pessimist about the human condition, would it really be too much to call Wool an optimist about the painting condition?", Jeff Perrone asked in Parkett, n°33, September 1992.

3 When he writes by hand, Wool tends to cross out certain words whose meaning, with effort, can still be deciphered.

4 Since 2001, the Polaroids have been replaced by digital photography

5 Gilles Deleuze, Presentation de Sacher-Masoch, coll. 10/18, Christian Bourgois ed., Paris, 1967. In English, see Gilles Deleuze, Masochism: Coldness and Cruelty, trans. Jean McNeil, New York: Zone Books, 1991.

6 East Broadway Breakdown will be published as a book by Holzwarth Publications in 2003.

7 On dogs, see the series of paintings and editions RUN DOG RUN (1991), BAD DOG (1992), Parkett n°33 and numerous photographs from Absent Without Leave and East Broadway Breakdown. On neurosis, see a poster made for an exhibition at Luhring Augustine Gallery in 1997 that lists the side effects of a medication, as well as certain phrases or words used in paintings like SELL THE HOUSE SELL THE CAR SELL THE KID (1988).

8 "The rhetoric of denial", denounced by Dave Hickey (Christopher Wool, review, Artforum, October 1998) is in fact one of the principal aesthetic strategies of modernity, shared by a whole set of artists with whom Wool claims kinship, from Dieter Roth to Larry Clark. It is not a matter of vowing not to say or do something but of recognizing and using the critical, creative, and liberating power of the negative.

9 Jim Lewis, Wool, in Christopher Wool, cat., The Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, Scalo, 1998. 29

10 48 Drawings, all, Untitled, 2000, enamel on rice paper, 66 X 48 inches, see the book, 9th Street Run Down, 7 L ed., Paris, 2001.