Christopher Wool: Katrina M. Brown

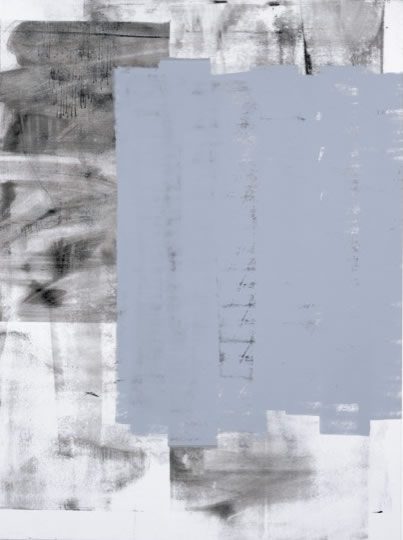

Christopher Wool. Untitled. 2003

One of Christopher Wool's most striking recent all-over abstract paintings at first appears to be almost entirely comprised of fluid brush strokes across the vast picture plane, carrying a dark grey/black over most of the surface. This is surprising when you consider that Wool is not known for free-flowing, gestural abstraction. On closer scrutiny, however, Untitled (2002) reveals itself to be a canvas that has been silkscreen printed in black (and a very little red) enamel; the screens are derived from photographs of his spray-painted marks made on other paintings. The whole has then been partially obliterated by rollered paint and erased — it is solvent, not paint that has been moved over the surface.

This is typical of the more densely layered make-up of his recent paintings, in which one technique will be imposed over another. The negation of what lies beneath amplifies the sense of aggression that has been present in his work, since the stark word paintings for which Wool first became known. In these paintings begun during the late 1980s, such as the iconic Apocalypse Nov (1988) (which reads 'SELL THE HOUSE SELL THE CAR SELL THE KIDS'. a quotation from Coppola's film), words hover on the brink of disintegration into abstract forms. The evenly-spaced letters, spread edge to edge across the surface of the painting, lack any punctuation. Stripped back to the basics in this way the words become almost unreadable. The question is always do you look at them or read them? Are they abstract monochrome compositions or clusters of signs that reveal a meaning? They are, of course, both. The urge to read and therefore to understand, to decipher what appears written, is perpetually interrupted by the insistence on the letters as forms. When meaning does emerge it is, as Thomas Crow has written, to 'recall the obsessive rants and catch-phrases of Travis Bickle-type casualties of the city.

A street-level vision of the world seems to permeate Wool's work. This is partially attributable to the tension between accident and intention set up by his paintings, which cannot help but feel intrinsically urban. However sparse and reduced the means of their making, they persist in conveying a strong sense of anger, even paranoia, an awareness of things that are not as they should be. The spills and drips, smudges and smears that punctuate his paintings echo the degraded surroundings that appear through his vast photographic work, East Broadway Breakdown (1994-5), exhibited for the first time in 2002. A group of 160 black and white photographs taken at night of the streets between his studio and his home in New York, they offer an unpeopled view of the Lower East Side's over-looked spaces and discarded objects. As true a picture of a city as any artfully rendered skyline.

Although his work undeniably entwines the two great legacies of postwar American art – Abstract Expressionism and Pop -– it is by no means polite reverence. Far from it; Wool's painting remains unapologetically new. He has continually challenged his own practice, never settling into a particular look. He may be seen to use the scale, vigour and vitality of Pollock's abstraction. The paintings may recall Pop Art's impoverished images and depersonalised means of production: Warhol's newspaper photographs. Lichtenstein's dots. But his challenge to that history pervades his work, most notably perhaps in his contribution to the 1991 Carnegie International in Warhol's home town of Pittsburgh. A vast word painting in the museum was accompanied by a number of billboards sited around the city, reading 'THE SHOW IS OVER', the painting's opening lines. Wool surely acknowledges the history of painting and the discourse around its continued possibilities, but the paintings are not dependent on that history. They function absolutely in the here and now of the viewer's encounter with them, grounded in a contemporary experience of the world. They are about looking, about visual language, as much as they are about, or rather from, the street.

Repetition has been a recurrent strategy, from the early all-over foliage motif paintings, in which it is key to the creation of pattern, through many of the word paintings (HELTER HELTER, SEX LUV SEX LUV, PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE, all Untitled (1988), RUN DOG RUN (1990) to the more recent THE HARDER YOU LOOK THE HARDER YOU LOOK (2001)), and also in a number of two-layer silkscreen works, in which the same pattern is repeated at a slight shift. making for a disconcerting tremble. There is also a perversion at the heart of much of Wool's work, not only in those paintings that take language – our fundamental tool for ordering thought and making it communicable – and make it difficult, but also in those pieces that take a benign tool for home decoration – the patterned paint roller, a cheap alternative to wallpaper and turn it into something dark. sinister, sick. Black is, after all, seldom the home improver's colour of choice.

Throughout his career and his ongoing fascination with image making, Wool has used various devices, readily-available techniques of mass reproduction, but seldom a painter's brush, He is undeniably a painter, but one who somehow always manages to insert a distance between himself and the painting: patterned paint rollers, stencils and, since the mid 1990s, silkscreen printing keep him at a slight remove. His black and white works on aluminium are devoid of many of the traditional characteristics of painting — the weave of canvas or the spontaneous brushstroke. Stripped of colour, they are reduced to the most straightforward mark-making. More recent works further undermine the ability to see the straightforwardly painterly — where gesture appears, especially in the spray-painted lines that are present throughout so many of his recent paintings — as it often reveals itself to be, in fact, printed. Marks and forms are processed to become endlessly reproducible: Wool uses photography to record them, producing silkscreens to re-use them. Elements recur enlarged, reversed. in different colours and configurations in further works.

Whether paint rollers, letter stencils, spray paint or silkscreen, Wool controls the chaos, to offer us a kind of primary viewing, the image as a pre-linguistic, pre-thought means of communicating. With their grand scale, bold, unapologetic presence and their stark. black and white confidence, Wool's paintings seem like the epitome of an indescribable urban cool, a tense fusion of intellect and emotion, control and chaos.